Climate change is increasingly perceived by world leaders as a top-tier geopolitical issue, with far-reaching implications for the future of the global economy, international cooperation and foreign security.

As COP26 President Alok Sharma has stated, the “golden thread” of climate action weaves through every international gathering in 2021. A clear understanding of the wider geopolitical picture is therefore essential for successful climate diplomacy this year.

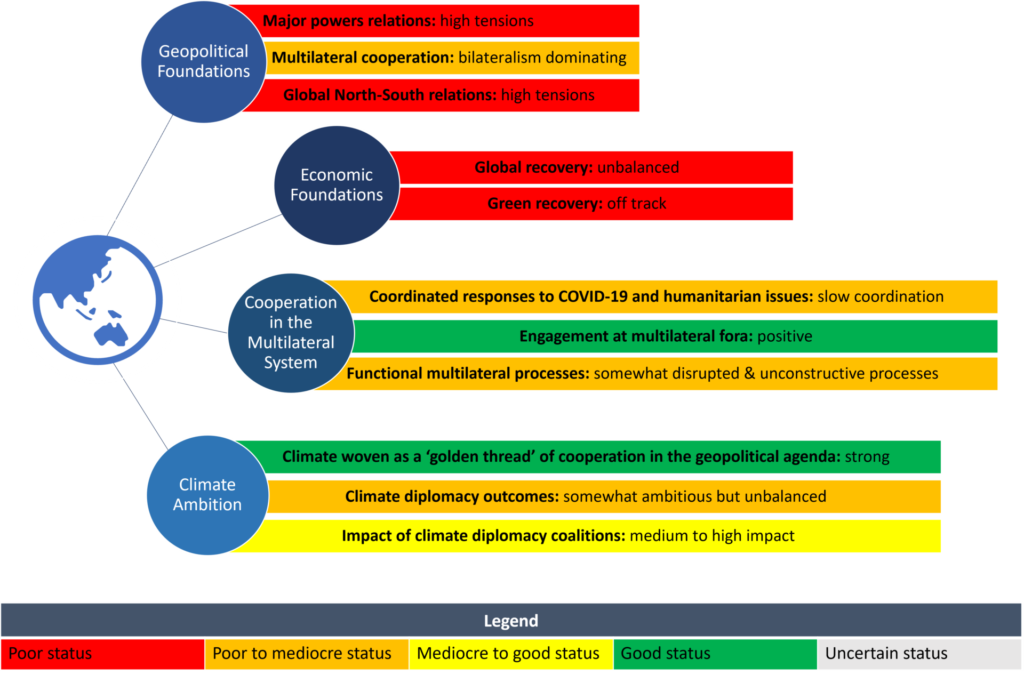

This ‘Geopolitical Snapshot’ is a tool that breaks down the geopolitical landscape into the core elements that are essential to the context of global climate action. By focusing on the factors that are crucial for climate action, this tool provides a concise framework for thinking through the position of climate diplomacy with respect to the wider geopolitical context.

For a comprehensive explanation of the colour coding for each indicator, please see the methodology. This Snapshot is taken with less than 30 days to go until COP26 and shortly ahead of the IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings and the G20 Leaders’ Summit. It is an update since the last Snapshot taken in April 2021.

Key takeaways

- Despite some recent signs of progress, insufficient cooperation on COVID-19 and global recovery has sustained tense geopolitical relations and an uneven global economic context. Throughout Q2/Q3, developing countries have continued to signal frustration with slow progress by wealthier nations to take sufficient action on vaccine equity and global recovery through the G7, G20 and other multilateral spaces. Since the UN General Assembly, commitments to reallocate Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and the joint US-EU commitment to vaccinate 70% of the globe by September 2022 have signalled emerging progress. However, the delivery of these initiatives will fall largely in 2022. The consequence for climate action is insufficient financial firepower and fiscal space to support developing countries in their climate transition which continues to limit countries’ confidence to raise climate ambition ahead of COP26.

- Whilst multilateral spaces remain open as prominent platforms for major powers – as evidenced by both the US and China using UNGA as a venue for climate announcements – fragmented bilateral or plurilateral approaches are dominating multilateral activity, creating new diplomatic challenges. From AUKUS to Afghanistan, Western powers have shown a hesitancy towards reasserting geopolitical power in multilateral contexts. The US has consistently prioritised bilateral approaches over multilateral avenues in its climate diplomacy, too. Announcements on development cooperation at UNGA hinted at further fragmentation: Biden reiterated his commitment to the Build Back Better World initiative, whilst Xi announced a ‘Global Development Initiative’, days after the EU revealed its own plans for the Global Gateway Initiative. Without multilateral coordination these pluralistic initiatives miss the opportunity to build confidence for higher climate ambition.

- Despite this context, climate change has continued to serve as a ‘golden thread’ of cooperation, standing out as a remarkably distinct area of sustained high-level international diplomatic engagement. Throughout Q2/Q3, leaders have taken more decisive action to put climate at the heart of key multilateral and plurilateral processes including the G7, G20 and at UNGA. This has supported delivery of tangible (if limited) climate outcomes that have helped build some momentum towards COP26. Climate remains a core area of open dialogue between the US, EU and China.

- As a result, there is potential political space for a high ambition outcome at COP26 that sets an acceleration pathway to close the gaps to the Paris Agreement goals in the early 2020s, as vocally called for from climate vulnerable country groupings. Such an outcome would cement the role of climate cooperation in sustaining faith in multilateralism, establish confidence in climate cooperation as a key lever in easing geopolitical rivalry, and help restore trust in relations between developing and developed countries. At the same time, the current global energy crisis which has seen sharp spikes in energy prices worldwide represents a potential wildcard for COP26 that could either make long-term decisions on climate action more domestically unpalatable and see an uptick in fossil fuel use this winter or reinforce the narrative around the benefits of a diversified energy portfolio for building economic resilience.

- A high level of ambition at the G20 Rome Summit on coal, net zero and 1.5C would signal strong willingness to revisit ambition for a 1.5C pathway at COP26. An ‘acceleration’ outcome at COP26 that can close the gaps to 1.5C has yet to receive vocal enthusiasm from developing country major emitters, especially China and India. However, with increasing progress on addressing climate vulnerable priorities on the $100bn through the US commitment to double climate finance and the Germany-Canada co-led delivery plan due on 18th October, major emitters are no longer as shielded from pressure on their ambition and are now facing strong calls from climate vulnerable country groups. A high ambition G20 leaders’ communique will be a core dynamic to unlock BASICs support for a COP26 decision on 1.5C at the COP26 World Leaders’ Summit the following day. To secure the pivot from Rome to Glasgow, the UK, EU and US will need rapid strategic coordination on finance – on the $100bn target and adaptation finance to build trust with climate vulnerables, and coordinating comprehensive investment offers to facilitate confidence in the green transition across low and middle income countries.

- Regardless of the outcome at COP26, 2021 has unlocked a new level of integration on climate action within top-tier geopolitical issues for world leaders. This is a foundation for further progress in 2022. Unlocking further investment in accelerating climate implementation can be a key focus of the German G7 Presidency and the Indonesian G20 Presidency, whilst core issues of adaptation, resilience and loss & damage – which have received insufficient attention throughout 2021 – can be progressed in the Egyptian COP27 Presidency.

This snapshot breaks down the geopolitical landscape into four key dynamics. These are the core geopolitical conditions for climate action in 2021.

Geopolitical Foundations: This examines relations between the major emitters: the USA, EU, China, OECD countries and large middle-income countries (BASIC). It also tracks Global North-South relations; COVID-19 has exacerbated global inequalities, but cooperation is crucial to build trust and solidarity ahead of COP26.

Economic Foundations: This tracks the strength, fairness and greenness of the global recovery, as this will define the fiscal and political space to address climate amidst the pandemic’s wide-ranging impacts on economies and societies. It also tracks the extent to which global trade remains open as this will guide economic trajectories, and both define and be defined by geopolitical relations throughout the year.

Cooperation in the Multilateral System: This captures the nature of cooperation between countries in the multilateral system. Effective climate action requires countries to cooperate within rule-based systems across trade, finance, resilience, development and other agendas.

Climate Diplomacy: This assesses the extent to which climate diplomacy processes and outcomes, interspersed across the G7, G20, COP26 and other fora, advances a cooperative geopolitical agenda. This also focuses on tracking the impact of climate coalitions. Shared action on climate change can demonstrate global cooperation and thus facilitate cooperative geopolitics to address wider challenges that COVID-19 has exposed to world leaders.

For a more detailed explanation of each of the indicators, including a delineation of its sub-indicators and metrics, please refer to the methodology.

Assessment:

Major power relations: High tensions

Multilateral cooperation: Bilateralism dominating

Global North-South relations: High tensions

Evidence:

- Tension in major power relations remains high, particularly as US-China tensions heat up over the Indo-Pacific; meanwhile, US unilateral decision making in its foreign policy increasingly hampers closer transatlantic alignment with Europe. The new security partnership between the US, UK and Australia (AUKUS) represents a new and deliberate strategic alliance to focus military pressure on China and its growing influence in the Indo-Pacific region. This has been echoed by leaders of the QUAD who continued to send clear signals to Beijing at the first-ever in-person group summit at the White House. As a result of heightened interest in the region, Indo-Pacific countries are increasingly pressured to take sides as US-China rivalry heats up. Japan and the Philippines have welcomed AUKUS, but Malaysia and Indonesia cautioned an escalating arms race, while India is pivoting to France. Countries in the region are also being in taking a stance on applications to join the CPTPP free-trade agreement by Beijing and Taipei. Perhaps as a silver-lining, the most recent bilateral exchanges between China and the US have been more friendly with the US arguing that competition could be managed responsibly. However, it remains to be seen how this will play out in practice given the remaining familiar sticking points and domestic agendas. Elsewhere, AUKUS significant diplomatic backlash. Catching diplomats by surprise, the sudden announcement of breaking Australia’s existing submarine procurement deal with France created friction among Western powers just as the EU launched its own Indo-Pacific Strategy. This has added to already complicated transatlantic relations, which had spiked as a result of the mishandled withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan. This reinforced perceptions of an inwardly focused US foreign policy rooted in domestic concerns, and dented trust in the reliability of US partnership. The rapid resurgence of the Taliban has been perceived as a failure of Western foreign policy and has demonstrated the limitation of Western power.

- Major powers have shown a strong preference for using bilateralism instead of multilateralism to solve diplomatic challenges. Countries continue to engage in multilateral spaces to some extent (See ‘Cooperation in the Multilateral System’). However, bilateral and plurilateral engagements have dominated geopolitical activities this year, from the QUAD and AUKUS to competing development cooperation vehicles spanning the G7’s Build Back Better World Initiative, the EU’s Global Gateway and China’s Global Development Initiative. For example, although COVAX remains a fora for international coordination on vaccines, the EU and US have prioritised their bilateral initiative to vaccinate 70% of the world by UNGA 2022 instead, in contrast to China’s commitment to a further 100m vaccines in bilateral aid. Hesitancy towards multilateral spaces outside of climate has done little to ease geopolitical tensions and hampers wider geopolitical multilateral cooperation. These dynamics open a clear role for climate cooperation via COP26 to be a positive force for facilitative geopolitical dynamics into 2022.

- North-South relations continue to be dominated by a lack of progress for a comprehensive plan to rapidly vaccinate the world despite better progress towards fulfilling the $100bn climate finance promise. Although an uptick in action is expected in the wake of Biden’s COVID summit, building on pledges from EU & US, these initiatives signal a hesitancy towards multilateral action on vaccines (see bullet above). Perceptions of global vaccine inequity have been sharpened by recent moves from Global North countries to roll out booster jabs. Climate finance commitments towards the $100bn are slowly restoring trust. The US has committed to double its climate finance and with further climate finance forthcoming from Italy and Belgium, with the forthcoming Germany-Canada Delivery Plan expected to build confidence around fulfilment of the $100bn. Additionally, the Champion’s Group on Adaptation Finance with countries from the EU and the UK was announced during UNGA, the group has issued a clear political commitment to work with developing countries to accelerate adaptation finance as well as inviting other climate finance providers to join them.

Assessment:

Global recovery: Unbalanced

Green recovery: Off track

Evidence:

- Initial concerns regarding an uneven global recovery from COVID-19 are being realised, which might be exacerbated in the near future if more fiscal space and action on vaccines is not provided. A recent UNCTAD report predicts the global economy will grow by 5.3% throughout 2021. However, this growth is fragmented across regional, sectoral and income lines and driven in part by unequal access to vaccines. While the IMF predicts that the US and China are on track to return to their pre-pandemic economic trajectories, Europe is at present lagging behind in its recovery. Inflation is starting to bite Europe as a result of general supply chain issues and general underinvestment over the previous decades. Elsewhere, numerous countries are still responding to, rather than recovering from, the impacts of the pandemic. The majority of economies are still lacking the necessary capital needed to invest in a strong recovery. In certain regions, most notably Africa and South Asia, the financial impact of COVID-19 exceeds that of the 2008 financial crash, and the UN predicts that the world’s poorest countries will be $12 trillion worse off by 2025 as global inequality continues to worsen. While G20 leaders’ Debt Service Suspension Initiative to suspend LDCs bilateral debt repayments showed some level of cooperation on debt relief, there has been little progress towards moving beyond this initiative set to end this year. There have been some limited positive steps, such as the unprecedented scale of the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) issuance and mutualising some debt in the European Union. But G7 and G20 leaders have not deployed enough firepower to address the crisis, let alone to begin to address the pre-existing structural challenges faced by the global economy including climate action. It remains to be seen how quickly to EU-US led announcements to vaccinate 70 percent of the world population by UNGA 2022 will have economic effects. (See Geopolitical Foundations.)

- Progress towards green, fair and resilient recoveries from COVID-19 has delivered poor results to date. Overwhelmingly, recovery has not benefited climate action, with only one-tenth of global recovery spent on emissions reductions and nature restoration. G20 country recovery packages have typically shown no systematic consideration of climate risk and preferred business-as-usual policies, incentives and investments which threaten to derail Paris goal efforts. In the EU, most recovery plans have not been aligned with the EU’s new 2030 climate target.

- Trade discussions focus increasingly on climate and how best to structure the global trading system to drive decarbonisation in major emitting economies. In Europe, the International Climate Clubs, proposed by Germany and the IMF, set out a framework for industrial decarbonisation that aims to be inclusive of developing and emerging economies. However, it remains to be seen how this proposal is advanced following post-election negotiations for a new governing coalition in Germany. It is also unclear at present what the concrete offer would be to developing and emerging economies, as the current proposal centres on G7/OECD countries. Questions likewise remain on whether the proposal is a vehicle for exporting carbon pricing or will look more broadly to accelerating industrial decarbonisation and preventing carbon leakage and whether green procurement standards will be included in the final proposal. Discussions around a proposed EU CBAM have likewise taken off following the publication of the EU Commission’s ‘Fit for 55’, sparking the interest of Russia and Turkey who would face sizeable fees under the current CBAM regulation proposal. The recent EU – US Trade and Technology Council resulted in an agreement to incorporate trade-related climate issues in the work plan, as well as explore how trade can help achieve climate neutrality and a circular economy. At the WTO, a potential agreement on fisheries subsidies at the 12th Ministerial could give breathing space to a broader green trade agenda.

Assessment:

Coordinated responses to COVID-19 and humanitarian issues: Slow coordination

Engagement at multilateral fora: Positive engagement

Functional multilateral processes: Somewhat disrupted and unconstructive processes

Evidence:

- COVID cooperation remains low, with the multilateral approach to the pandemic struggling to respond at adequate pace or scale. Only 2% of 5.7 billion vaccine doses administered globally have been in Africa. Countries such as Egypt and Morocco have stepped up regional leadership and proposed to produce vaccines within their countries for national and continental use, however much of the roll out strategy remains to be developed. Progress towards securing a TRIPS waiver for vaccines at the WTO – as prominently called for by South Africa and India – remains sluggish despite new support from Australia, following support from the USA, Russia and China. The lack of cooperation to unlock this issue mirrors similar fragmentation in response to the WHO investigation into the origins of COVID, which China has resisted, seeking to divert focus on other countries. An initial WHO inquiry was inconclusive as the data provided by China was insufficient to determine COVID’s origins.

- Countries are willing to engage at multilateral fora and there is rising appetite to revive multilateralism. Most prominently, the leaders of Costa Rica, New Zealand, Sweden, South Africa, Senegal and Spain collectively endorsed the UN Secretary General’s ‘Our Common Agenda’ calling for a revival of rules-based multilateralism. Major powers see multilateral spaces as effective platforms. For example, both the US and China sought to use the UN General Assembly as a platform for new climate commitments. However, there are doubts over the extent to which some, particularly major powers, have prioritised bilateralism instead. (See “Geopolitical Foundations”.)

- Multilateral spaces continue to struggle with being fully functional with a slow, gradual and challenging return to in-person diplomacy. Whilst parties in the CBD have moved to postpone the formal negotiations until next year, the UNFCCC remains on track to hold COP26 in-person – despite protest from civil society with concerns over safety and equity of participation. The UNFCCC’s virtual May-June SBs saw limited progress on negotiating issues with many parties raising concerns over how progress would be captured and developed in a virtual setting towards COP26. There were also notable concerns over moves by some parties to exclude observers from certain negotiating items, sparking fears over the inclusivity of virtual diplomacy. In person diplomacy in many other fora has resumed (albeit to a limited extent) with mostly hybrid or face to face meetings at UNGA, the G7 and G20. China is notably more hesitant about high level in-person diplomacy with doubts over whether President Xi will attend the G20 Leaders’ Summit and COP26 Leaders’ Summit. However, coalitions from vulnerable countries such as AOSIS and the CVF have argued that they may struggle to meet visa requirements and cover all COVID-19 related costs for COP26, raising concerns that some might not be able to attend in person. This raises questions on the representation and equity of COP26 if delegates and civil society from vulnerable countries are not able to attend.

Assessment:

Climate woven as a ‘golden thread’ of cooperation in the geopolitical agenda: Strong

Climate diplomacy outcomes: Somewhat ambitious but unbalanced

Impact of climate diplomacy coalitions: Medium to high impact

Evidence:

- Climate remains a key geopolitical priority and drives national-level political discourse, whilst serving as a distinct area of cooperation despite the challenging geopolitical and economic context. Both the G7 Leaders’ and G20 Climate & Environment Ministers’ communiques saw strong and prominent climate outcomes despite the geopolitical barriers to climate cooperation, offering a basis for future international cooperation on a wide range of crosscutting issues stretching from sustainable infrastructure to ending public financial support for coal. President Xi’s commitment to phase out international coal finance at the UN General Assembly (UNGA) showed multilateral spaces still operate for climate despite tense geopolitics. The announcement followed weeks of intense diplomacy by the US and the UK, in which we saw US climate envoy John Kerry and UK minister Alok Sharma going to China and speaking with their counterparts and Chinese leader, marking climate outcomes as a notable area of productive diplomacy. Climate was a key issue in national elections too. It featured significantly in the recent German, Norwegian and Canadian elections, ranking high on voters’ topics of concern – demonstrating how climate continues to penetrate national-level politics with geopolitical repercussions.

- Multilateral and bilateral diplomacy throughout Q2/Q3 has unlocked critical climate outcomes, although overall ambition remains low, and progress has been biased towards emissions reductions over addressing climate impacts. UNGA was dominated by climate. Beyond China’s coal commitment, President Biden committed to double US climate finance to $11.4bn. These came off the back of an EU-US joint pledge at the Major Economies Forum to cut their methane emissions by 30% over the coming decade. However, these announcements are contrasted by persisting gaps in climate ambition, as summarised in the recent NDC synthesis report. To achieve a high-ambition COP26 countries, especially the 11 G20 countries who have not done so, need to revise their NDCs ahead of Glasgow. There has also been a particular lack of progress towards outcomes on adaptation and loss and damage. Despite being topics of interest at the UK July Ministerial and Pre-COP, the discourse around how COP26 can address these priorities remains underdeveloped compared to conversations on how to close the emissions gap to 1.5C.

- Climate coalitions are more actively coordinating as COP26 nears, particularly developing country groups which are adopting aligned positioning in advance of Glasgow. The Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) has issued a steady stream of regional communiques from ministers in Africa & the Middle East, Asia and Latin America & the Caribbean in recent months, as well as an overall COP26 Manifesto and a Climate Leadership Group Statement at Pre-COP. The High Ambition Coalition (HAC) is also notably more actively coordinating around COP26, issuing clear demands on the G20 to step up ambition, as have AOSIS who also issued a leaders statement outlining its COP26 priorities at UNGA. LDCs have also issued a minister-level COP26 vision. Together these alliances have contributed to firmly setting expectations on the G20 and COP26 to step up ambition, and their effective coordination has helped facilitate productive dialogue on the road to COP26. However, the orientation of BASIC countries remains more opaque. There are some hints of shifts towards climate action – notably India’s commitment to a new 2030 climate target in the QUAD statement and South Africa’s updated 2030 climate target – but this is yet to translate into a clear, aligned group position into COP26.