Climate change is increasingly perceived by world leaders as a top-tier geopolitical issue, with far-reaching implications for the future of the global economy, international cooperation and foreign security. As COP26 President Alok Sharma has stated, the “golden thread” of climate action weaves through every international gathering in 2021. A clear understanding of the wider geopolitical picture is therefore essential for successful climate diplomacy this year.

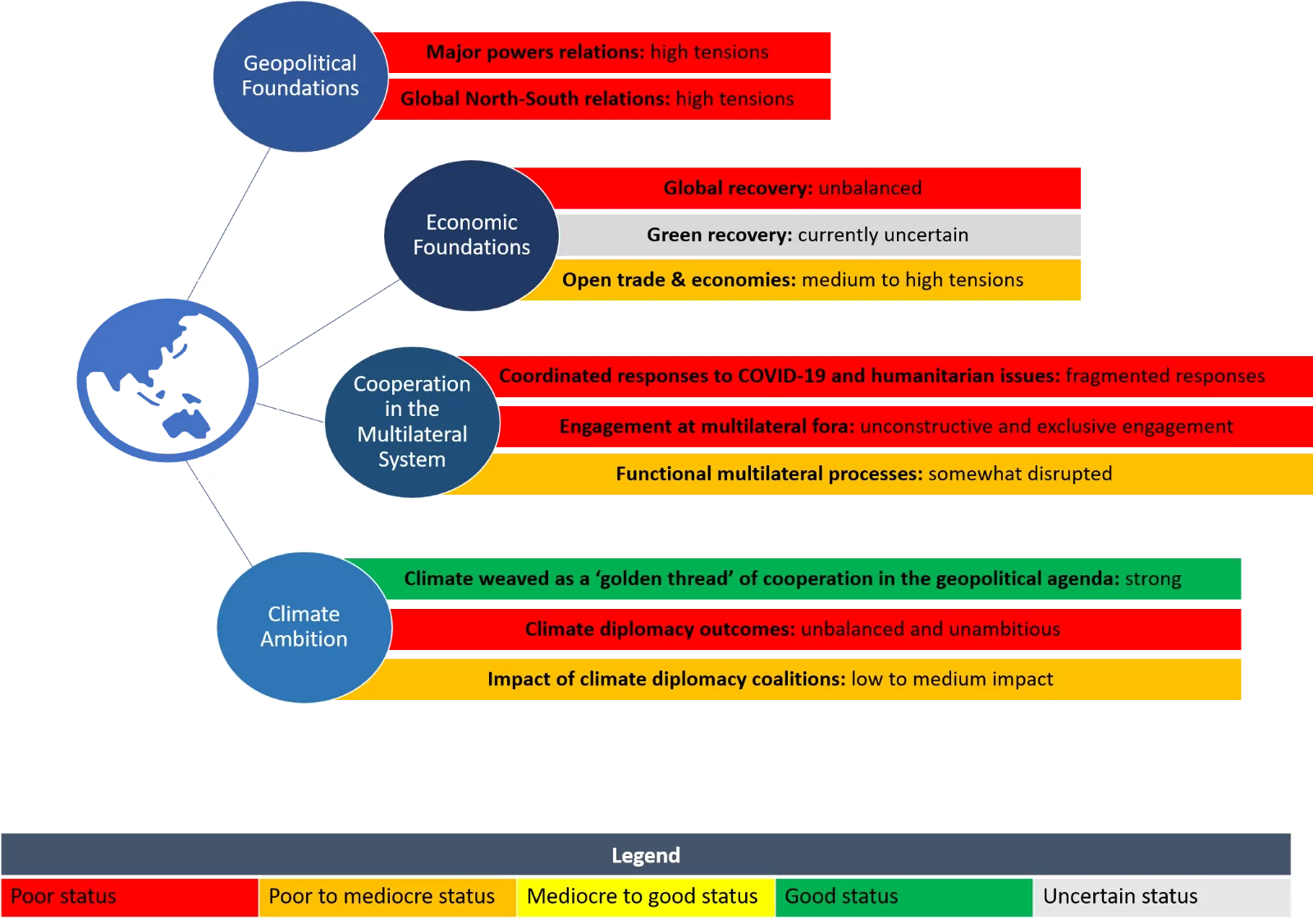

This ‘Geopolitical Snapshot’ is a tool that breaks down the geopolitical landscape into the core elements that are essential to the context of global climate action. By focusing on the factors that are crucial for climate action, this tool provides a concise framework for thinking through the position of climate diplomacy with respect to the wider geopolitical context.

This Snapshot is taken ahead of President Biden’s Leaders’ Summit on Climate (22-23 April). Further snapshots will be shared ahead of critical leaders’ level meetings at the G7 (11-13 June), UN General Assembly (14-30 September), G20 (30-31 October) and ultimately COP26 (1-12 November).

April 2021 – Geopolitical Snapshot

For a comprehensive explanation of the colour coding for each indicator, please see the Methodology.

This snapshot breaks down the geopolitical landscape into 4 key dynamics. These are the core geopolitical conditions for climate action in 2021.

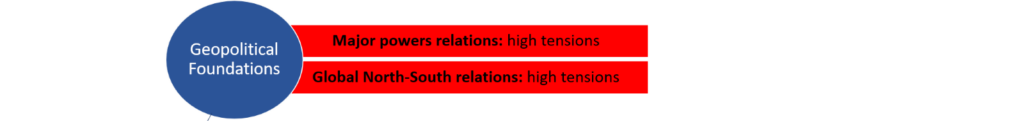

Geopolitical Foundations: This examines relations between the major emitters: the USA, EU, China, OECD countries and large middle-income countries (BASIC). It also tracks Global North-South relations; COVID-19 has exacerbated global inequalities, but cooperation is crucial to building trust and solidarity ahead of COP26.

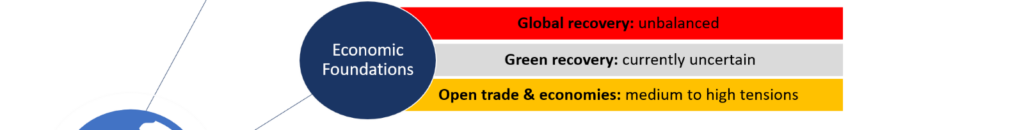

Economic Foundations: This tracks the strength, fairness and greenness of the global recovery, as this will define the fiscal and political space to address climate amidst the pandemic’s wide-ranging impacts on economies and societies. It also tracks the extent to which global trade remains open as this will guide economic trajectories, and both define and be defined by geopolitical relations throughout the year.

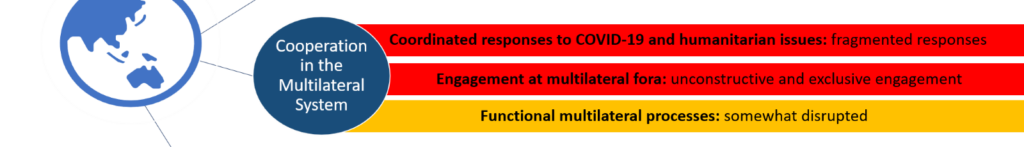

Cooperation in the Multilateral System: This captures the nature of cooperation between countries in the multilateral system. Effective climate action requires countries to cooperate within rule-based systems across trade, finance, resilience, development and other agendas.

Climate Diplomacy: This assesses the extent to which climate diplomacy processes and outcomes, interspersed across the G7, G20, COP26 and other fora, advance a cooperative geopolitical agenda. This also focuses on tracking the impact of climate coalitions. Shared action on climate change can demonstrate global cooperation and thus facilitate cooperative geopolitics to address wider challenges that COVID-19 has exposed to world leaders.

For a more detailed explanation of each of the indicators, including a delineation of its sub-indicators and metrics, please refer to the methodology.

Key takeaways

- Climate features prominently on the geopolitical agenda, but so far 2021 has seen a failure of leaders backing up strong political narratives on climate with concrete, ambitious outcomes. The pathway for securing greater progress depends on establishing strong geopolitical alliances to raise pressure for climate action. This will be crucial for the US-China relationship, as both sides have disagreed over the extent to which climate is a ‘standalone’ issue for diplomacy. The US Leaders’ Summit on Climate will be the first test of whether climate remains a walled-off technical issue, or an issue of clear national interests backed up by action and engagement at leaders’ level.

- Climate has emerged as a clear foundation for strengthening transatlantic relations in Q1 2021 and is high up the G7 and G20 agenda. However, this will need to translate into stronger strategic coordination between the US, EU and UK if transatlantic cooperation is to secure ambitious outcomes by the G7 Leaders’ Summit (11-13 June). Finance ministers are not currently translating political will into coordinated efforts to mainstream climate action across the global economic system and within green, fair and resilient economic recoveries. Priority areas for progress at the G7 Finance Ministerial (early June – TBC) include climate reforms of multilateral development banks, international fossil fuel finance phaseout, and cooperation on green investment standards. These agendas can be picked up at the G20 Venice Climate Summit (11 July), laying solid foundations for wider G20 climate leadership in the second half of 2021, building positive tailwinds for climate action towards COP26.

- North-South relations are strained by inadequate efforts to support COVID-19 response and recovery globally. Climate cooperation tensions also remain high given the under-delivery against the 2009 promise by developed countries of $100bn annually in climate finance to developing countries. Equitable vaccine distribution, the acceleration and escalation of efforts to unlock fiscal space in developing countries, and additional climate finance are critical steps for rebuilding climate progressive alliances between developed and developing countries that will be essential for brokering ambitious climate outcomes in 2021. Delivering on the action plan set out by the UK Climate & Development Ministerial (31 March) is an opportunity to improve relationships in this area. Key outcomes and venues for progress on these critical issues will be new climate finance commitments at the G7 Foreign and Development Ministerial (3 May), trust-building towards COP26 negotiations at the Petersberg Climate Dialogue (6-7 May), global vaccine rollout at the G20 Global Health Summit (21 May) and leaders-level cooperation at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (21 June).

Assessment:

Major power relations: High tensions

Global North-South relations: High tensions

Evidence:

- Relations between the EU, US and China have deteriorated throughout 2021. US-China engagements have been defined by belligerent language and grandstanding, in continuation with Trump-era relations, with regional anti-China alliances (such as the Quad and expanding the G7 to include Indo-Pacific democracies) taking increasing prominence. Joint sanctions from the EU & USA (supported by the likes of Canada and the UK) were levied against China in criticism of human rights abuses against the Uighur Muslim population, triggering retaliatory sanctions. The exchange has generated doubts over the ratification of the EU-China investment agreement and may prompt closer alignment between the EU and US taking a harder position with respect to China, in contrast to previous months where a more nuanced EU approach to China compared to the USA’s tougher stance. The heightened interest in the Indo-Pacific as a strategic priority for the UK, EU and the USA reflects the volatile nature of relations with China in the region. The appointment of a new OECD chief with a poor record on climate change nonetheless is reflective of strong alliances between like-minded democratic countries.

- Trust between developed countries and the Global South remains strained, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to exacerbate global inequalities. As of 9 April, 87% of COVID-19 vaccines worldwide have been administered in high- and upper-middle-income countries; in contrast, just 0.2% of doses have been administered in low-income countries. Some political tailwinds have risen in recent months, with COVAX now beginning to distribute vaccines globally and G20 countries backing actions to address fiscal space (see Indicator #2). Nonetheless, headwinds prevail: there are signs of donors reducing international aid, and few donor countries have yet to commit to increase climate finance towards reaching the $100bn goal – a key step towards building North-South solidarity.

Assessment:

Global recovery: Unbalanced

Green recovery: Currently uncertain

Open trade & economies: Medium to high tensions

Evidence:

- There are major concerns around the prospects for recovery from COVID-19 diverging significantly across countries. The IMF is warning of the risks of a ‘Great Divergence’ and projects by the end of 2022, cumulative per capita income will be 13% below pre-crisis projections in advanced economies, compared with 18% for low-income countries and 22% for emerging and developing countries (excluding China). This is partly due to disparities in COVID-19 vaccination but has been exacerbated by shrinking fiscal space in Global South countries; a recent communique from African finance ministers stated, “Our fiscal buffers are now truly depleted”. Although G20 countries, with G7 support, are poised to back the issuance of $650bn in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF and extend the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), further commitments to reallocate SDRs to the developing world and to scale up global vaccine supply are still needed and a recent AOSIS statement has called for deep structural reforms of the global debt system.

- It is too early to make a robust judgment on progress towards green, fair and resilient recoveries, though so far leaders are yet to deliver ambitious action. The economic response to COVID-19 to date will reinforce negative environmental trends. High-level pledges to support green recovery are often not accompanied by concrete measures and funding, and many governments continue to support high-carbon recovery strategies. However, many countries are yet to transition from early stimulus packages towards enacting recovery programmes, particularly in the Global South where recovery is at risk (see above). Expectations have risen in light of the USA’s $2 trillion recovery package with a strong emphasis on green infrastructure but the proposals fall short of what is required for decarbonisation goals and its passage through Congress remains uncertain. In the EU, many states still risk falling short of the 37% climate spending target. There has been a missed opportunity for cooperation between countries to advance green recoveries, with no institution or multilateral fora taking responsibility for setting shared standards and guidelines.

- Concerns over trade tensions remain despite the change in the US Administration. With Biden in the White House, some (but not all) tariffs between the EU and US have been lifted. However, many crucial trade disagreements remain. Digital services taxation remains a potential flashpoint for future tariff impositions. It is not yet clear whether the US will support a common approach through the OECD-led process, although support is rising for a global approach to corporate taxation. Meanwhile, trading tensions between the US and China remain high, with no indication that Trump-era tariffs would be lifted, whilst both countries continue to pursue an emphasis on self-reliance via reshoring of critical supply chains. Although the US poured cold water on the EU’s forthcoming proposals for a carbon border adjustment mechanism, the disagreement may push the EU into taking a more coordinated approach to the contentious issue. COVID-19 continues to suppress international travel, with extensive border restrictions in place across much of the world.

Assessment:

Coordinated responses to COVID-19 and humanitarian issues: Fragmented responses

Engagement at multilateral fora: Unconstructive and exclusive engagement

Functional multilateral processes: Somewhat disrupted

Evidence:

- Humanitarian needs remain unmet and the multilateral approach to COVID-19 pandemic response has struggled to meet the global demand for vaccinations and health interventions. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing challenges, resulting in a 40% increase in the number of people needing humanitarian help. UN-led approaches to crises in Syria and Yemen remain under-funded despite pledging conferences. World leaders are falling short of meeting expectations for the WHO-led COVAX Initiative, ceding greater space for bilateral ‘vaccine diplomacy’ to be effective, where vaccines are used as a tool for soft power and diplomatic influence, particularly as the likes of the EU enact vaccine export restrictions. COVAX rollout still lags behind that of bilateral initiatives, particularly China. China’s early lead in exporting vaccines to other countries has spurred the Quad to initiate their own vaccine drive, though it is expected to face blocks as vaccine production in India is diverted to domestic priorities. Despite growing support for a new pandemics treaty there is a shortfall of contributions to the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), a crucial mechanism for supporting strained health systems. Wealthy nations oppose relaxing WTO rules on intellectual property so that more drug manufacturers can freely make vaccines – an issue pushed by India, South Africa and other developing countries.

- Multilateral cooperation in UN and other global spaces is stymied by geopolitical rivalries. The UN Security Council failed to condemn the coup in Myanmar and remains stuck on taking humanitarian action in Syria. Elsewhere, the UN Human Rights Council has become split into opposing blocs on the question of taking action against human rights abuses in China, rendering the forum ineffective; notably, more signatories have joined a statement led by Cuba in defence of China since last October. Vulnerable country access to decision-making spaces remains problematic; for example, many small island states are excluded from the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and only one Pacific Island state (Marshall Islands) has been invited to participate at the US Leaders’ Climate Summit.

- There are large disparities between the extent to which the pandemic has impacted the functionality of multilateral spaces. COVID-19 continues to push the vast majority of climate diplomacy online, with lingering uncertainty as to how progress on UNFCCC negotiations will advance and whether COP26 will take place in-person this November. However, nature negotiations under the CBD are already confirmed to be taking place online and virtual meetings have been adopted in other fora such as the IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings. Many developed countries and the UN Secretary General are supporting virtual talks. Like-Minded Developing Countries remain opposed to them. BASIC Ministers are warming towards virtual negotiations provided sufficient measures are taken to overcome challenges faced by developing country negotiators.

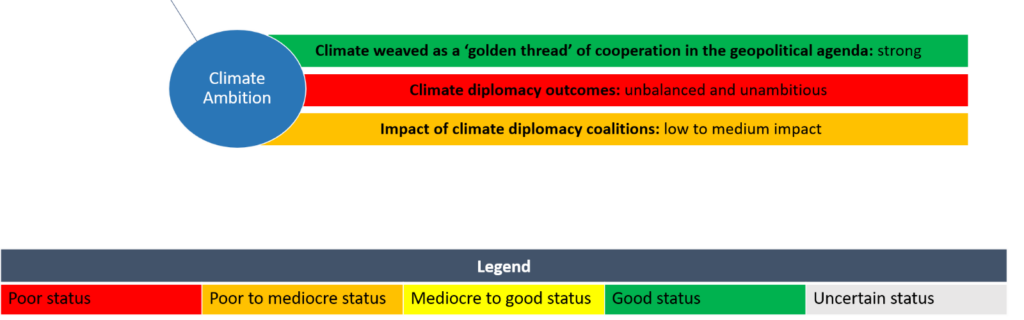

Assessment:

Climate weaved as a ‘golden thread’ of cooperation in the geopolitical agenda: Strong

Climate diplomacy outcomes: Unbalanced and unambitious

Impact of climate diplomacy coalitions: Low to medium impact

Evidence:

- Climate is operating as a foundational area for global cooperation in key geopolitical fora this year. In sharp contrast to the previous US administration, climate now sits at the heart of efforts to rebuild transatlantic alliances, as evidenced by its prominence in early leaders’ level dialogues between the USA and partners in Europe, and the first major leaders’ summit of the year will focus on climate change. Climate is also a top priority issue for both the G7 and G20, with it emerging as a focus area for finance and trade ministers as well as climate and environment ministers.

- Overall climate ambition outcomes this year remain disappointing and unbalanced, with particularly inadequate progress on adaptation and financial system reform. After a flurry of mitigation ambition commitments made in late 2020 at the UK’s Climate Ambition Summit, a key priority of early 2021 has been raising the profile of adaptation and resilience issues. The UK’s Climate and Development Ministerial last month has successfully kicked-off the process of rebuilding trust with developing countries, though delivery on its stated aims for the year on adaptation, loss and damage and finance remains crucial to demonstrating true solidarity with climate vulnerables. On mitigation and finance, China’s 5 Year Plan fell short of expectations that it would deliver a comprehensive roadmap towards achieving China’s carbon neutrality goal. So far 2021 has seen few new ambition commitments. However, expectations for significant new ambition on NDC, coal and finance from the USA, Canada, Japan, South Korea and South Africa are rising ahead of the US Leaders’ Summit on Climate and the G7 in June.

- Climate coalitions have held early 2021 coordinating meetings, but have had limited impact so far this year, though the absence of UNFCCC negotiations has constrained opportunities somewhat. Although most negotiating groups are taking part in Presidency-led consultations held in lieu of negotiations, so far there is a low level of coordination between climate coalitions resulting in impactful outcomes on negotiating agendas. Beyond a recent virtual meeting of HAC ministers there is little evidence of coordination between climate vulnerable coalitions and climate progressive major powers. A recent virtual meeting of BASIC Ministers, the AOSIS-hosted Placencia Ambition Forum (and recent statements on green recovery and debt relief) and the LDC-hosted Thimphu Ambition Summit all indicate a limited extent of virtual positioning ahead of COP26, but fall short of delivering effective coalition-building required to land ambitious outcomes this year.

Contributors: Nick Mabey, Shane Tomlinson, Alex Scott, Jennifer Tollmann, Byford Tsang, Jule Könneke, Rishi Kumar, Daniela Schulman, Taylor Dimsdale, Ronan Palmer, Sima Kammourieh, Dileimy Orozco, Anna Glasser, Dido Gompertz