The creditability of the Paris Agreement is contingent on a considerable uptick in climate action over the next cycle. The Paris Agreement was forged by a pact between countries which said the world would protect the most vulnerable by aiming to cap warming at 1.5°C. But if current mitigation efforts don’t shift up a gear – and fast – the credibility of this pact will be under threat.

Old arguments have taken us some distance but not far enough. In this blog I weigh up whether escalating climate impacts could be harnessed as a force for good and catalyse climate action.

How have climate impacts shaped the debate?

Not a whole lot.

The climate science of impacts sounded the starting gun for climate action. But climate impacts themselves are not perceived to play a dominant role in shaping national interest debates on commitments to climate action – especially mitigation action. In the run up to COP21 in Paris, developed country responsibility and low carbon opportunity were in the driving seat.

This is partly because many countries do not have a serious understanding of their climate vulnerability. This is particularly stark in developed countries who dangerously perceive impacts on their own security to be marginal. For example in the EU 6 of the 28 member states do not have national adaptation plans and many others are underdeveloped. What’s more second order impacts (systemic e.g. food supply chain, water etc) and third order impacts (political e.g. conflict) often go unrecognised. Again taking the EU as an example, despite the ongoing refugee crisis its adaptation strategy has no mention of climate induced migration from climate vulnerable neighbouring countries. In many cases climate impact events aren’t connected to climate change, or the need for urgent climate action and are too often written off as ‘bad weather’. As 100 year events become 10 year events become 3 year events, this cannot continue.

The 43 countries of the Climate Vulnerable Forum are a notable exception. Their mantra to ‘survive and thrive’ explicitly articulates that, despite their low level of emissions, their vision for prosperity means all citizens have access to low carbon resilient transition. This approach tipped the balance in negotiations and did land a more ambitious deal but now the baton is passed to high emitting countries to demonstrate their credible commitment to achieving 1.5°C.

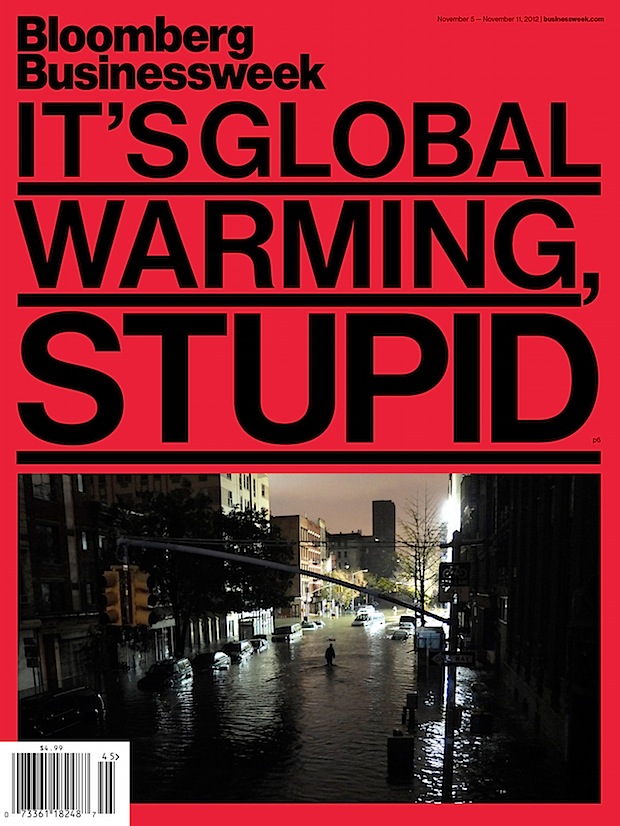

The US is another country which, perhaps surprisingly, has seized impacts as a way to drive the debate and break their world-famous climate denier deadlock. For example, the 2012 front page of Bloomberg Businessweek following Hurricane Sandy read ‘Its Global Warming, Stupid’. Many have highlighted this moment as pivotal in joining the dots between climate risks and the financial sector. Similarly in California the enduring drought has prompted extensive commentary on its links to climate change and the urgency of climate action.

Could climate impacts change the debate for good?

Yes but it won’t be easy.

There is no escaping climate impacts, they will undoubtedly change the debate. But harnessing their disruption for good will take some serious effort.

First we need to allocate responsibility. Even in sectors where they see and feel the climates devastating impacts they do not always see action to mitigate and adapt to climate change as their responsibility. This was stark during the World Humanitarian Summit where drivers of humanitarian disaster shifted from conflict and natural disasters to conflict and climate. But despite recognising climate change as a massive challenge to effective humanitarian action, the humanitarian community were not united in advocating for climate solutions.

There are many benefits to be gained by advocating and/or delivering climate action – less conflict for resources, greater resilience to ongoing climate events etc – but few who wish to absorb that into their already overwhelming humanitarian briefs. There is also a lack of understanding and confidence in how to deliver this. Some changes are being made on the ground by immediate necessity but in an era of prolonged crises these approaches will only be truly climate resilient in an era of prolonged crisis if combined with scientific and technological expertise.

Second we need to organise and maintain agency. Climate advocates have been held hostage to climate scepticism for a long time. Now that time has (thankfully) passed we must not isolate ourselves and engage in battles on our turf. We must work more collaboratively with the many that are impacted by climate. It will be a considerable challenge to build agency and not entrench despair but cooperation with a diversity of impacted communities could unlock a new politics of possibility and shape national interest debates.