Decarbonising the European energy system by 2050 will require a fundamental shift for the way the gas industry operates, away from business-as-usual in network planning and market design. Achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in Europe, in line with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, leaves no room for fossil gas consumption where CO2 is not captured and stored. But turning the gas industry into a zero-carbon industry is no simple task.

Decarbonising the gas sector using new forms of gas alone could become more challenging and costlier than is often suggested, according to a recent paper from E3G, an independent climate change think tank. It examined the three most commonly promoted alternative forms to the direct use of fossil gas and found the European gas sector faces a bigger transformation than is often portrayed, as gas volumes and markets will fundamentally change, even if new forms of gases develop.

Our study looked at three pathways for gas: hydrogen produced from fossil gas in what is called ‘steam methane reforming’, hydrogen produced through electrolysis using renewable electricity in what is often called ‘power-to-gas’ and biogas or biomethane from crops or waste.

Based on their climate impact, technical and economic potential and compatibility with the current gas network, we concluded there are four reasons why current ways to plan gas networks and operate gas markets are no longer apt to accompany the transformation to a zero-emissions world.

First, climate. We found that not all these forms of gases are compatible with the transition to a net-zero emissions society, something that could turn out to be the EU’s target by 2050. Biogas or biomethane can only be emissions-free if produced by taking into account sustainability of production methods and wider system boundaries. The exact criteria and instructions to monitor this are yet to be defined.

The alternative, hydrogen, can be net-zero emissions only if produced using renewable electricity, not if produced from fossil gases through steam methane reforming, even if that uses ways to capture the CO2.

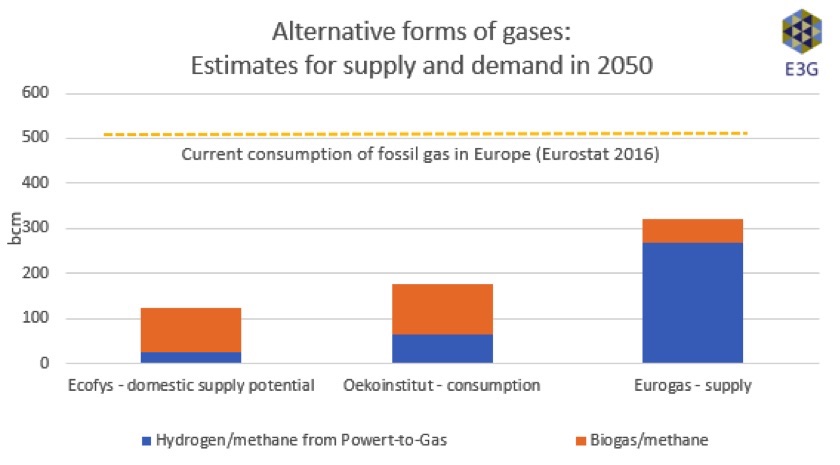

Second, volume. Genuinely zero-emission forms of gas are very short in supply compared to the current volume of our networks, leaving an already underutilised network even more so. While industry estimates vary substantially, they agree that the domestic potential of sustainably-sourced biomass and power-to-gas electricity will not be able to make up for current fossil gas volumes.

As a result, most studies examining the decarbonisation of the European energy sector assume a high degree of electrification and energy efficiency.

Third, economics. At the moment, zero-emission gases are outcompeted by fossil gas, electricity and demand-side measures, in most instances. Where there is no alternative to the use of gas, significant political or financial incentives (whether through a sufficiently high carbon price, specific quotas or feed-in tariffs) would need to ensure demand shifts from fossil to zero-emission forms of gas. For the power sector, gas concerns would also face competition from batteries, demand-side response and electrification, when it comes to short-term balancing.

Fourth, compatibility. The existing gas infrastructure was built with fossil gas properties and sources in mind. The use of biomethane, in turn, could require us to adapt from a highly centralised, transmission-focused network into one fed from the bottom up. Rural-based generation centres would not necessarily lie anywhere near where demand is.

Power-to-gas produces hydrogen, which would require large-scale adaptation of the network and appliances for safety purposes, the costs of which are, to date, uncertain. The conversion of hydrogen to methane to avoid this requires costly and energy-intensive new infrastructure to source and transport CO2.

The time has come to end all support to fossil gas infrastructure

So what should policymakers do? Emissions in the gas sector need to be addressed as part of the EU’s energy transition. There are a number of tools at hand: cutting demand, electrification or zero-emission forms of gas. The latter will initially need to be focussed on where there is a dearth of technological alternatives, such as for decarbonising industrial heat and as a feedstock for industrial processes. Limited scale and significant uncertainties mean they are far from a silver bullet to achieve EU decarbonisation objectives.

With this in mind, we believe policymakers should focus on the following points:

- Accelerating electrification and energy efficiency. The decarbonisation of the European gas sector should not act as a drag on the necessary investments in net-zero emissions power generation, the electrification of heat and the systematic roll-out of energy efficiency.

- Ensuring that all network planning scenarios are sufficiently detailed for investors to assess risks. The EU 2050 roadmap and/or member states’ long-term plans could help investors understand the future value of gas infrastructure. This requires setting out a range of detailed pathways for achieving the net-zero emissions target that permits the weighing up of alternatives including, among others, electrification, decommissioning of networks or investments in battery storage. This could also inform discussions around how to prioritise the use of truly zero-emissions gas, which, as mentioned, is likely to be scarce.

- Adapting the regulatory and institutional environment to ensure sustainability of all forms of gases. The current framework could face push-back from environmental groups as it does not safeguard against land use impacts and competition with food production, or provide science-based emissions accounting rules. Policy instruments also need to make zero-emission gases genuine competitors to fossil gas with the eventual goal of its phaseout, for example when reviewing the current gas market design regulation.

- Developing ways to test the scalability and network impacts of introducing zero-emissions gases where they contribute to phasing out fossil gas. The time has come to end all support to fossil gas infrastructure. Funding and developing scalable pilots now could help better understand the economically and environmentally sustainable contribution these new forms of gases can make to a transition away from fossil gas.

With all this, we believe it is worth continuing to explore the potential for genuinely zero-emission gases for some purposes, such as industrial heat. It can become a solution where energy efficiency, demand-side response and electrification will not take us all the way. But let there be no illusions that decarbonising all of today’s gas will be an easy task.

Notes

This article first appeared in Energy Post.

E3G Director Jonathan Gaventa is one of the speakers at Energy Post’s debate in Brussels on 27 September: How can gas contribute to the achievement of the EU climate targets? Sponsored by Nord Stream 2, attendance is free but registration is requested. You can register here.