The European Commission’s newly proposed EU budget is about to step into a tense two-year negotiation process. Straddled with great expectations, the proposal is not much bigger than its predecessor and does little to close Europe’s investment gap. Yet, it also puts on the table a major architectural overhaul that delivers agility in exchange for giving EU capitals greater weight in EU spending. Within this restructuring, climate action retains a 35% foothold but faces a new set of challenges and opportunities as the budget and its stated objectives are set to undergo a lengthy debate.

An EU budget proposal forged in a time of crises

The EU budget debate is always a contentious one, yet this year’s proposal arguably comes at a historically fraught juncture. Following years of crisis, the EU finds itself in a context where the newly proposed Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) – the financial backbone supporting EU objectives – is heaped with unprecedented expectations. From competitiveness to security, to climate breakdown and social pressures – a persistent investment gap sits at the core of almost every strategic challenge the bloc now faces. Add to this the recent economic pressures of the US administration’s tariffs and a reshuffling of the international order, and the EU budget – seen as complex and rigid – must suddenly step up as a pliable tool for answering urgent needs requiring collective EU action.

In this setting and faced with a political landscape that does not easily lend itself to ambitious shifts in policy, President Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission has put forward an MFF proposal that walks a tightrope of significant reform constrained by tenuous politics.

Major restructuring will meet pre-existing political fights for a long negotiation road ahead

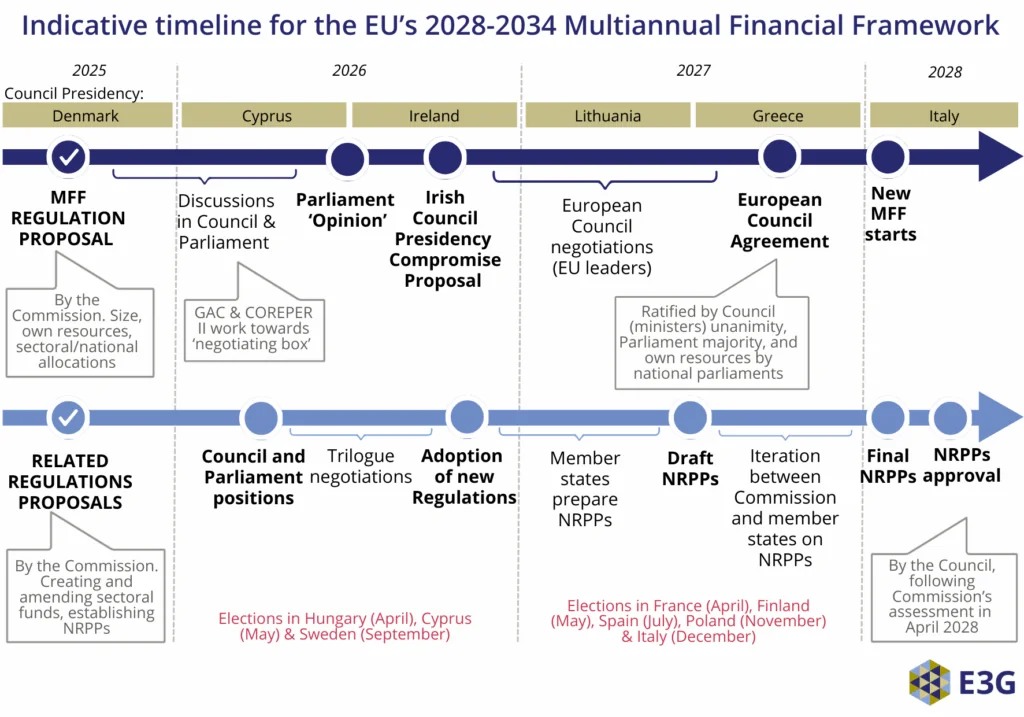

Held under tight wraps until its release, the bumpy presentation of the new MFF has hinted at the difficult road this package will face over the next two years. In the set of proposals put forward, the Commission proposes a minimal increase in size while introducing a step-change in architecture aimed at greater flexibility.

The political trade implicit in this proposal gives member states more control over spending while reducing the size and rigidity of some politically sensitive programmes. At the same time, the Commission grants itself enhanced means to connect EU spending to the delivery of EU policy priorities at national level.

Redirecting funds from traditional priorities draws attention but major restructuring has deeper implications

The aspiration to make the EU budget ‘simpler, more flexible and more strategic has led President von der Leyen to propose a shift in the balance of the MFF. Much attention has focused on the consolidation of multiple funds under the direct management of the European Competitiveness Fund and on the shift of resources away from traditional areas like agriculture and regional development towards this new fund and other centrally managed programmes such as the Connecting Europe Facility and Horizon Europe.

However, it is the restructuring of the way that the traditional funds will operate that represents a more fundamental shift in the architecture and philosophy of the EU budget. Drawing heavily on the experience of the post-Covid Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), these changes would give the Commission greater oversight not only over EU funding for the competitiveness agenda, but also over national policy decisions.

The first step of this restructuring is to merge Cohesion policy, Common Agricultural Policy and smaller migration and home affairs funds into a mega-programme that, while smaller than the sum of its pre-xisting parts, still accounts for almost half of the MFF.

The second step is to replace the traditional shared management of funds between local, regional and national authorities with the ‘RRF model’. This would see governments negotiate ‘national and regional partnership plans’ (NRPPs) with the Commission, with the role of regional authorities still up for debate. EU funds would be disbursed upon completion of agreed policy changes and targets , and member states would have greater freedom in how to spend them.

This would replace the current multilevel governance system with one where power lies mainly with national governments – likely finance ministries – and the Commission uses its role of negotiating and assessing national plans to exert greater oversight over national policy decisions. In turn, the European Parliament would relinquish significant oversight power, and EU regions risk losing their current role in co-determining the allocation of EU funds – a fact that has ushered in immediate pushback from both sides.

Climate and energy investment in the next MFF would be significantly shaped by the advent of NRPPs. NRPPs would have to address the common objectives set out in the regulation, complemented by the country-specific recommendations issued by the Commission as part of the European Semester annual budgetary monitoring process. National drafting processes would thus become critical junctures to secure climate measures, and the eventual contents of individual NRPPs – and the Commission’s assessment of their reform and investment commitments – would become essential indicators of climate ambition in the 2028–2034 period.

Several high-profile political battles will shape MFF negotiations, with most critical decisions Likely to be made at the end of the process

While Germany and France seem broadly supportive of the proposed budget’s architectural redesign, overall immediate reactions already paint a picture of challenging negotiations ahead, with key battles likely to include:

- Cuts to agriculture and regional development funding and the centralisation-versus-decentralisation debate associated with the introduction of the NRPPs are two newly opened political battles that will come to shape this round of MFF negotiations.

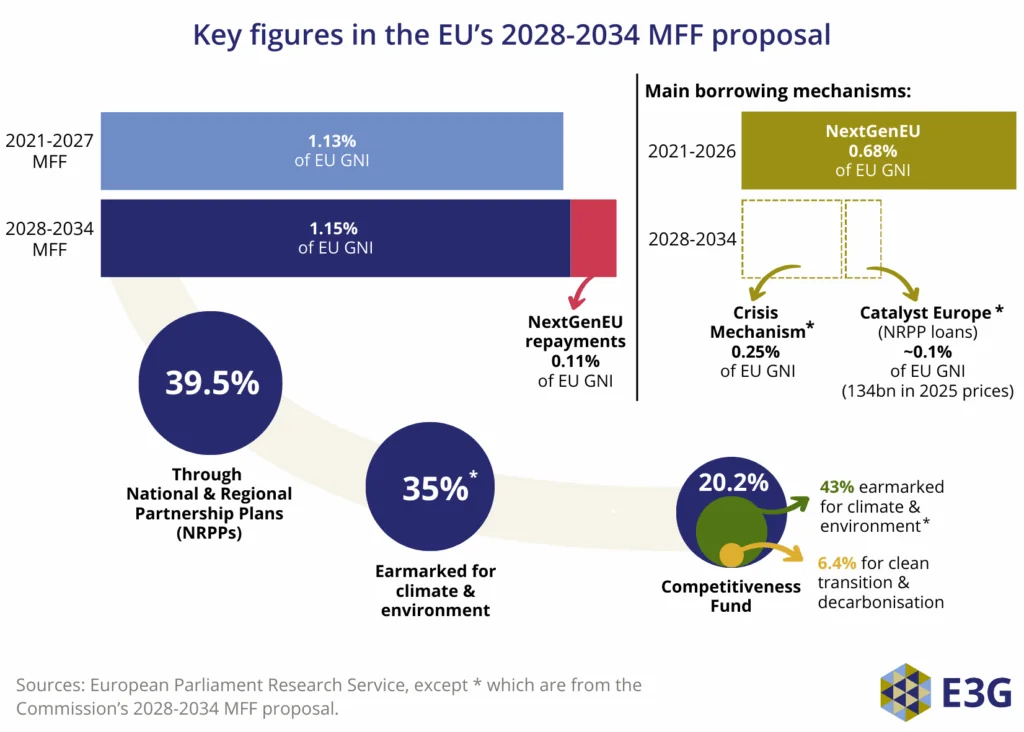

- The overall size of the budget has historically been the hardest question to resolve and tends to be tackled at the highest political level towards the very end of the negotiation process. By tabling a modest increase relative to the current budget (from 1.13% to 1.15% of EU GNI), President von der Leyen has erred on the side of caution vis-à-vis national governments, as opposed to the more ambitious position of the European Parliament. Yet the so-called ‘frugal’ member states – those who tend to be net contributors to the budget, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden – have already come out to oppose any growth in the budget.

- New own resources underpin the small budget increase to make up for some of the additional costs of repaying the post-COVID debt instrument NextGenerationEU and avoid major additional contributions from national budgets. The Commission has proposed a mix of technical adjustments – such as bringing a share of the revenue from the Emissions Trading System and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism into the EU budget, a national contribution based on the volume of non-collected electronics – and two new taxes: a tobacco levy and a tax on multinationals. The latter, the Corporate Resource for Europe (CORE), is the latest in a series of Commission proposals to make European and foreign multinationals that benefit from access to the Single Market contribute to its functioning, and which have repeatedly been stalled in the Council where unanimity is required. It is therefore unlikely to be adopted.

- Two new loan mechanisms for member states have been proposed in response to the European Parliament’s request to consider further joint borrowing. Totalling up to €545bn in total in current prices, they would support the implementation of NRPPs and be mobilised for future crisis response. Although they fall short of matching the NextGenerationEU mechanism in terms of either size, purpose, or ease of activation, they have already come under fire from frugal member states.

Source: European Parliament Research Service, except* which are from the Commission’s 2028-2034 MFF proposal.

Grading the MFF proposal for climate: What looks good and what leaves homework to be done?

The benchmarks below grade the Commission’s MFF proposal against the key elements needed for securing a fast, fair and funded transition in the EU and internationally.

Assessment: The 2028–2034 MFF grows slightly (from 1.13% to 1.15% GNI), with strong support for energy links and new loan tools, but overall spending declines as NGEU ends. The design of new borrowing mechanisms and new own resources can be detrimental to overall green spending.

Grade: Difficult

Assessment: A stable climate trajectory is signalled by the proposed 35% climate earmark, the ‘Do not significant harm’ principle across the budget and the link of NRPPs to a fair green transition. But broad objectives, weak tracking, an unclear role for regional and local authorities, and the absorption of the LIFE programme undermine credibility.

Grade: Mixed

Assessment: The new MFF clearly prioritises the EU’s competitiveness, including via a Competitiveness Fund with 43% climate earmarking and a dedicated stream for decarbonisation and the clean transition. Despite its broad coordination toolkit, it lacks social conditionalities and its impact hinges on private leverage and member states’ co-financing.

Grade: Has potential

Assessment: The MFF would boost energy infrastructure through a fivefold increase in the ‘Connecting Europe Facility – Energy’ stream (in nominal terms), ensure consistent investments across key areas such as grid infrastructure and energy savings, and fully exclude coal-to-gas conversions. However, member states could take advantage of lax eligibility criteria and avoid complementary investments.

Grade: Has potential

Assessment: While the Social Climate Fund for addressing ETS2 impacts is maintained, the absence of a dedicated Just Transition Fund and optional territorial plans, along with the Competitiveness Fund’s focus on strategic industries, risks leaving some regions and citizens on the sidelines of the green transition, as well as potentially overshadowing NRPPs’ 14% social spending target and the inclusion of investment for social housing.

Grade: Difficult

Assessment: The MFF proposes to strengthen the EU’s global role with a 37.9% increase in the external action budget. It also supports climate and development priorities with better alignment and financing. But by removing thematic targets and increasing Commission discretion, it risks undermining the credibility, coherence and predictability of EU partnerships.

Grade: Mixed