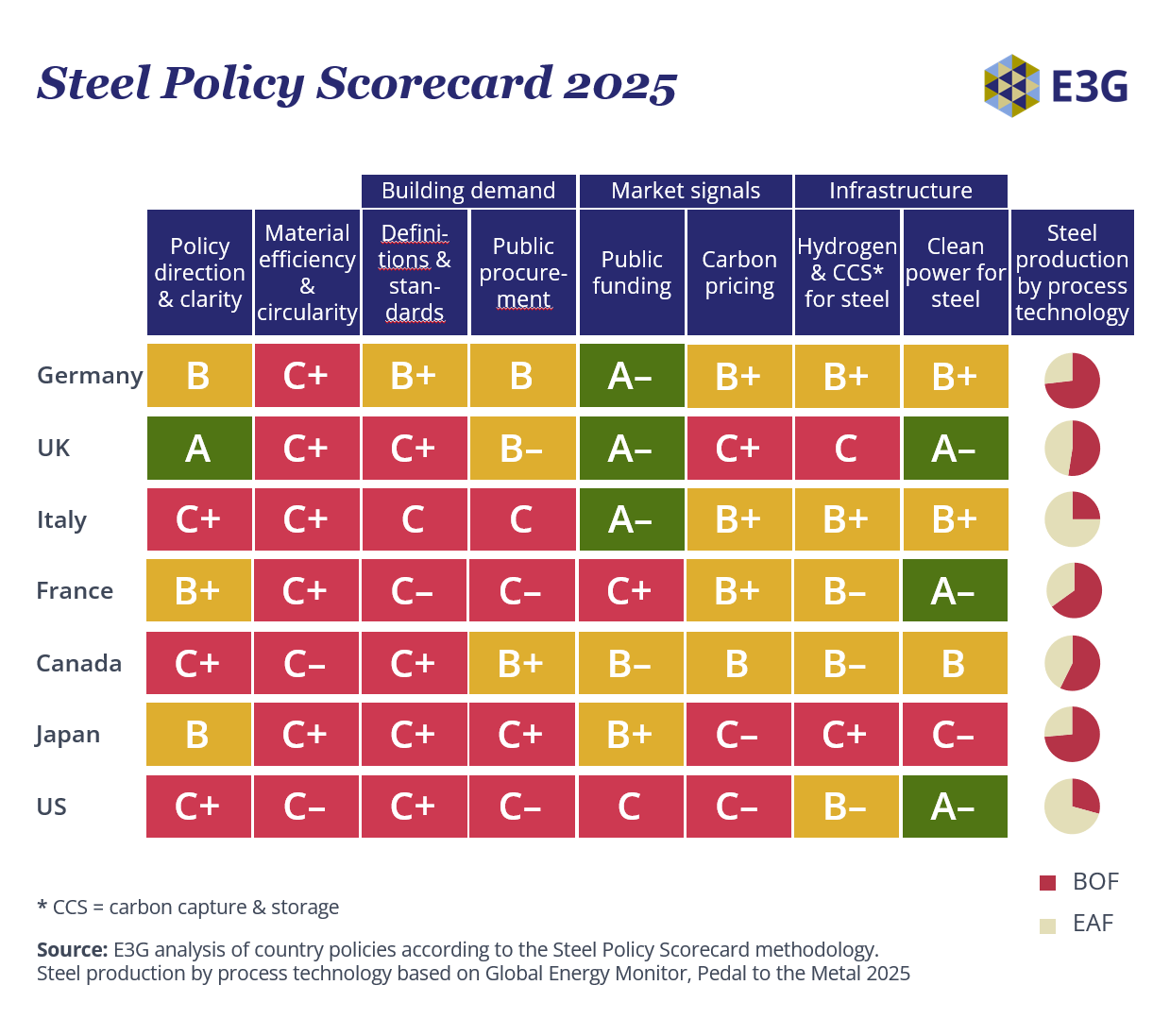

The 2025 edition of E3G’s Steel Policy Scorecard assesses progress on steel decarbonisation across the G7. We find that while ambition has advanced, delivery remains insufficient and fragmented. Without systemic change, the sector risks falling behind the pace of global industrial transformation required, undermining climate goals, economic resilience, and the ability to meet growing demand for low-carbon steel.

Efforts to decarbonise steelmaking are entering a decisive phase. The 2025 Scorecard assessment indicates improvements across several levers, including overall policy direction, public funding, procurement, and infrastructure build-out. However, near-zero emissions steel projects have been stalling and even cancelled in the majority of G7 countries, making it harder for them to position themselves as front-runners.

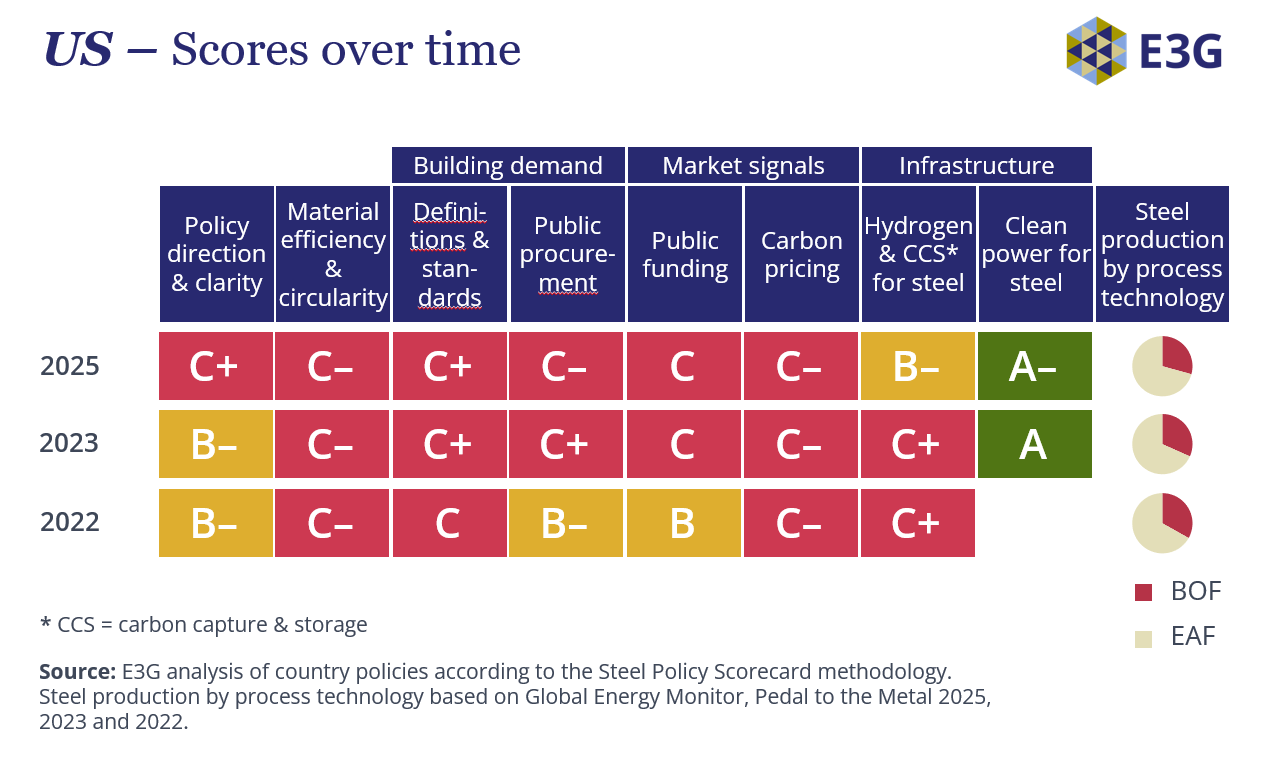

These developments are unfolding against a backdrop of intensifying political headwinds. Rising trade tensions and industrial policy rivalries are destabilising the global steel landscape. While some countries are pursuing collaborative approaches – through alliances like the Climate Club and the Industrial Deep Decarbonisation Initiative (IDDI) – others are retreating to protectionism. In some jurisdictions, notably the US, progress has been rolled back, with ratcheting steel tariffs undermining international momentum and investment certainty.

These tensions hamper the global coordination required to scale near-zero emissions steelmaking. At the same time, persistently high energy prices have delayed the commercialisation of key decarbonisation pathways in Western Europe – such as hydrogen-based direct reduced iron (H-DRI) – despite significant public financial support.

Beyond the G7, the pipeline for new coal-based steelmaking capacity is still growing and outstripping clean capacity additions. India alone is planning to build 200 mtpa of coal-based steelmaking capacity. G7 countries have a critical role to play in providing support to shift overseas steel investments and speeding up the global transition.

To get on track, the G7 must prioritise rapid deployment of clean, affordable electricity for industry, alongside renewed cooperation on standards, finance, and trade. A key test in the years ahead will be whether countries can reconcile national industrial strategies with global supply chain optimisation. That includes recognising that locating parts of green steel production – such as low-cost green iron – in energy-rich countries may offer the most competitive path to industrial decarbonisation.

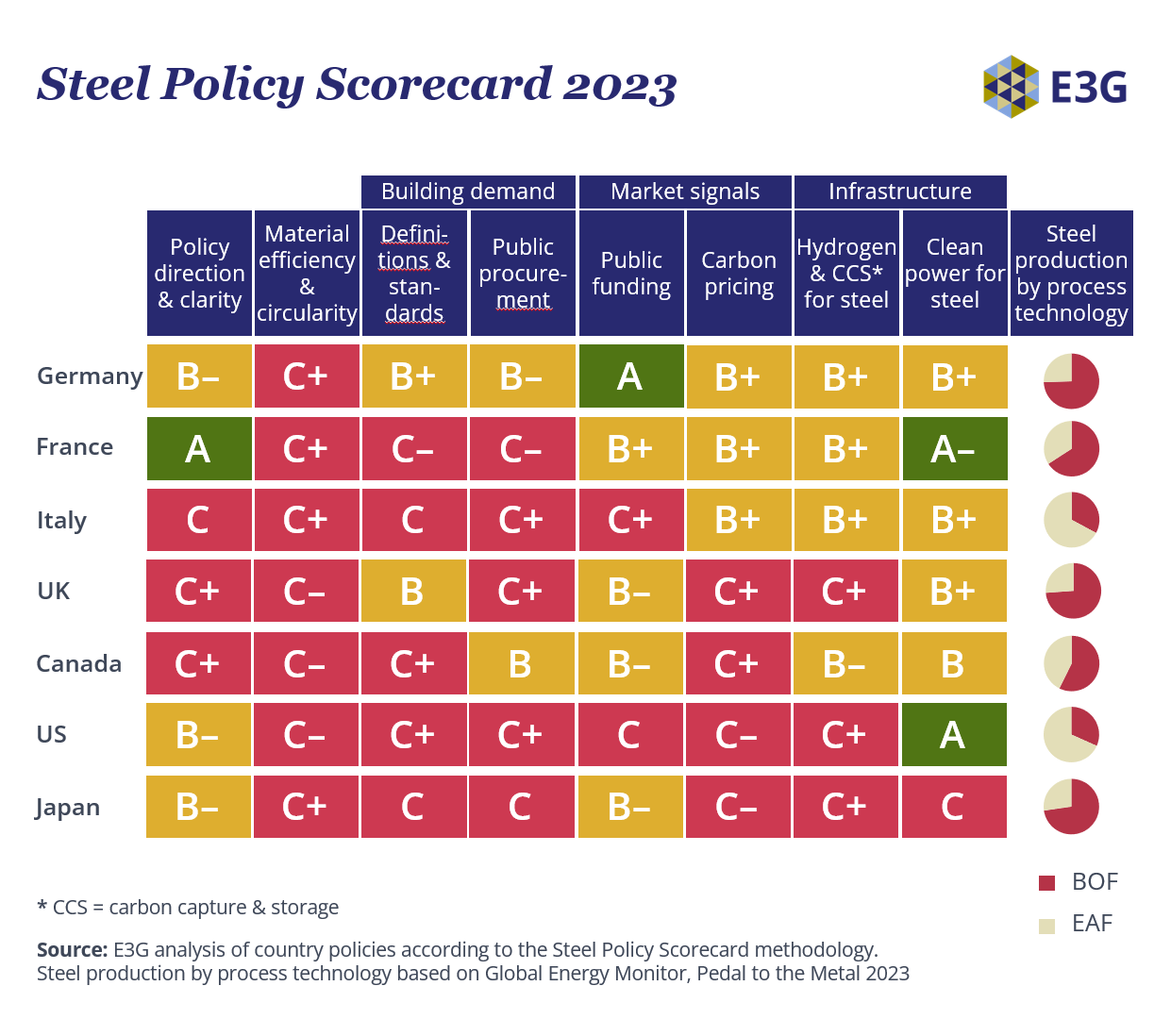

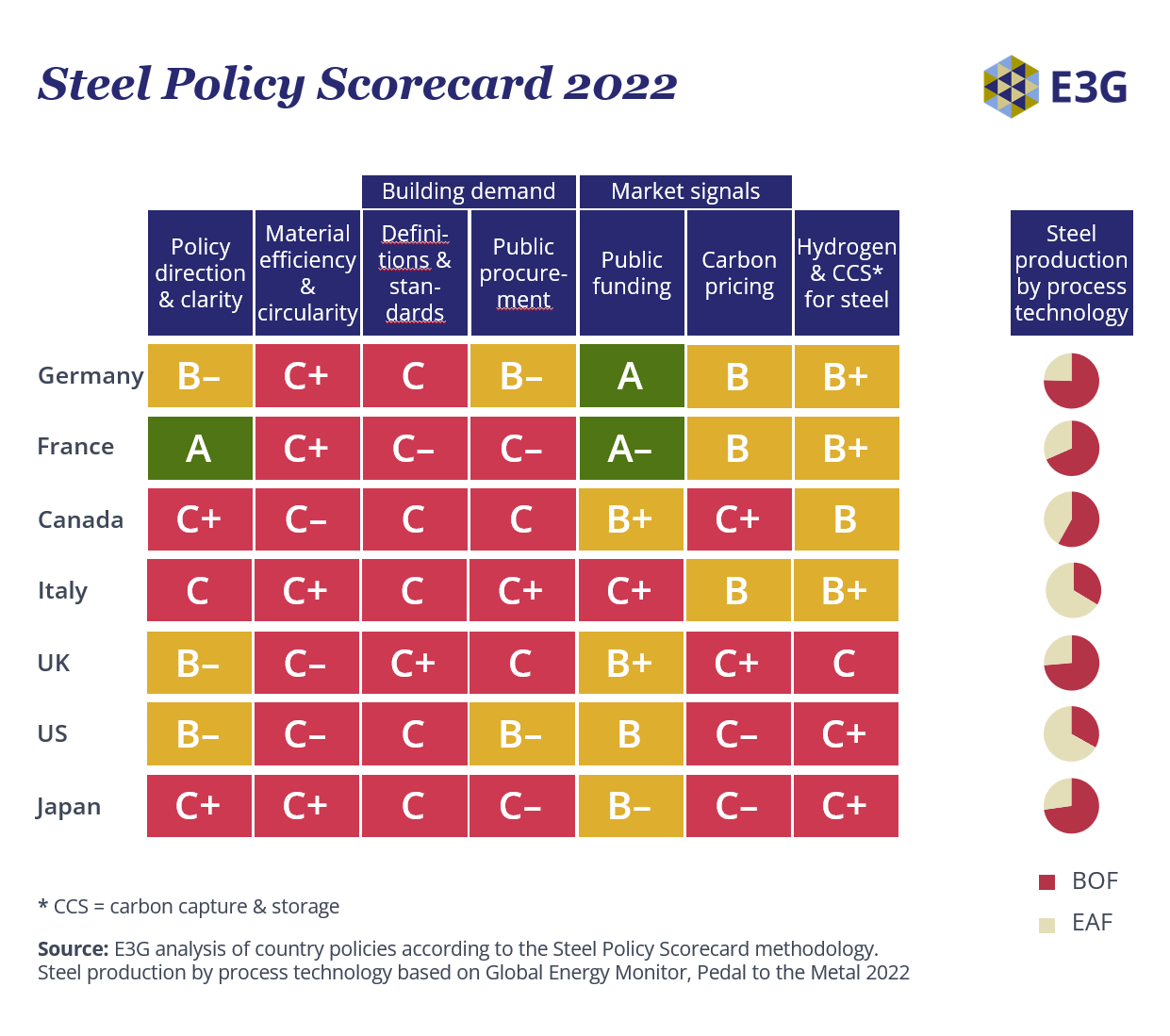

Key findings from the 2025 Steel Policy Scorecard

Tangible progress remains slow. Scores have improved in several categories compared to our last assessment in 2023, indicating an uptick in policy progress, but red still dominates the picture. Demand-side policy and circularity initiatives still lag behind, and while strategic policy direction and public funding have improved, they have not created enough progress on real green steel demonstration projects and enabling energy infrastructure.

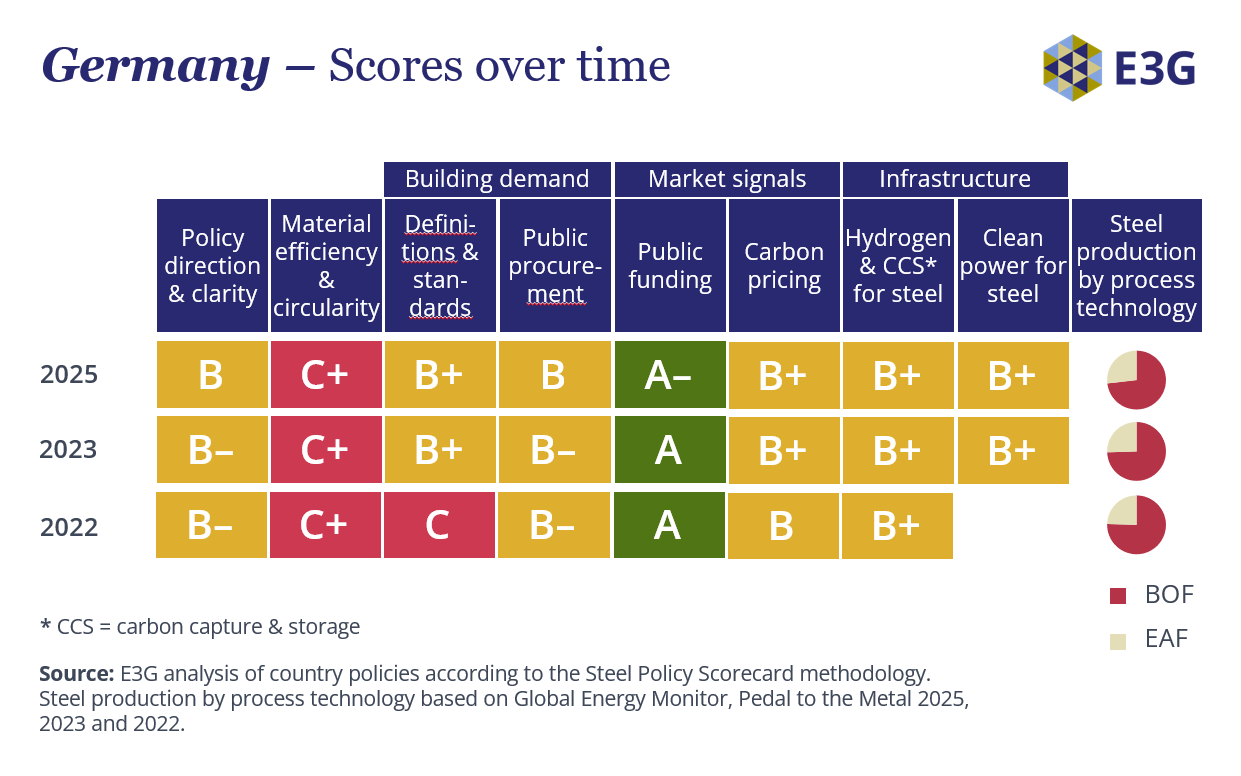

Germany is still leading in most policy categories, despite political shifts and corporate governance issues. Both policy uncertainty and high hydrogen prices have contributed to project delays. The freshly elected coalition government has committed to maintain the carbon contracts for difference (CCfD) policy to support industrial transition. However, Germany may lose its competitive edge, unless it meaningfully accelerates policy action, in particular on the Low Emission Steel Standard (LESS), which is still under development and which it aims to be adopted internationally.

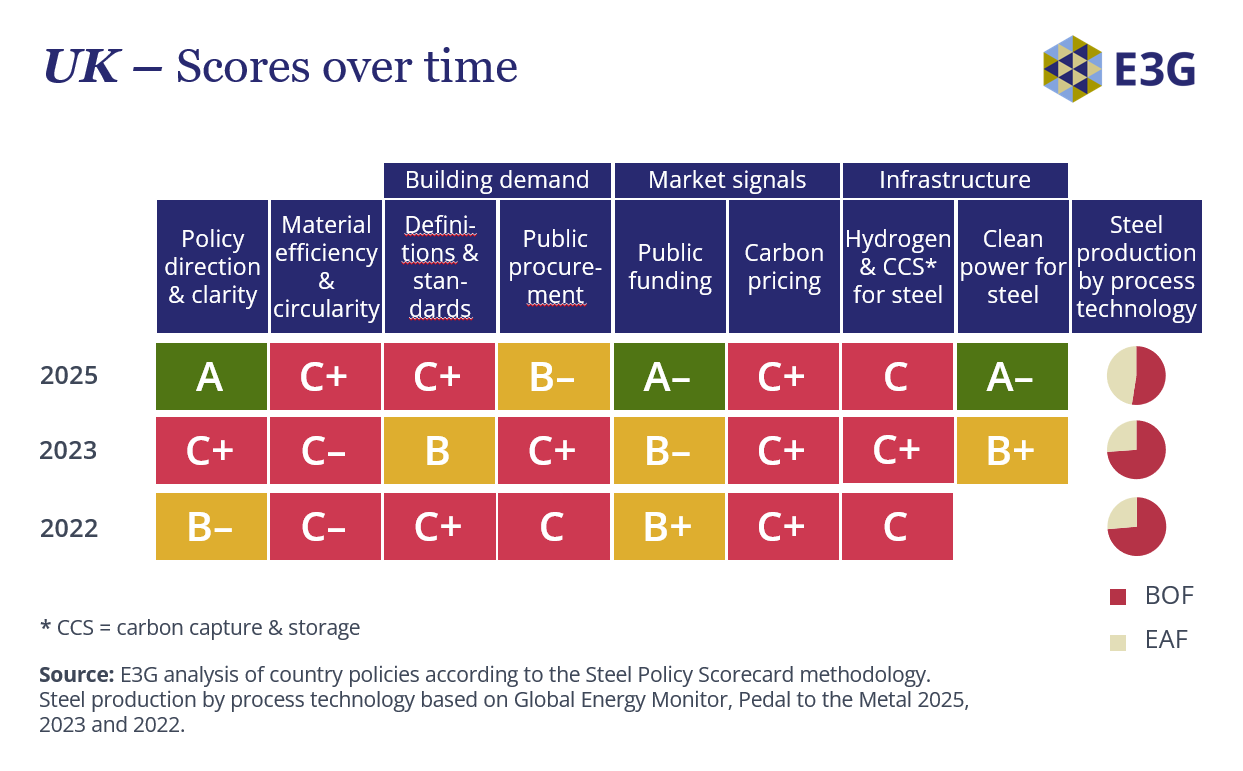

The UK rises to second place due to progress on its 2030 power decarbonisation target – including reforms to the grid connections process – and progress phasing out its last blast furnaces. The government has intervened to support British Steel and granted Tata Steel £500m to switch to an electric arc furnace (EAF) by 2027, potentially cutting sector emissions by 85%. However, this high score masks deeper challenges: years of underinvestment have led to crisis-driven subsidies, not strategic transition, with job losses, capacity risks, and no plan yet for domestic virgin steel production.

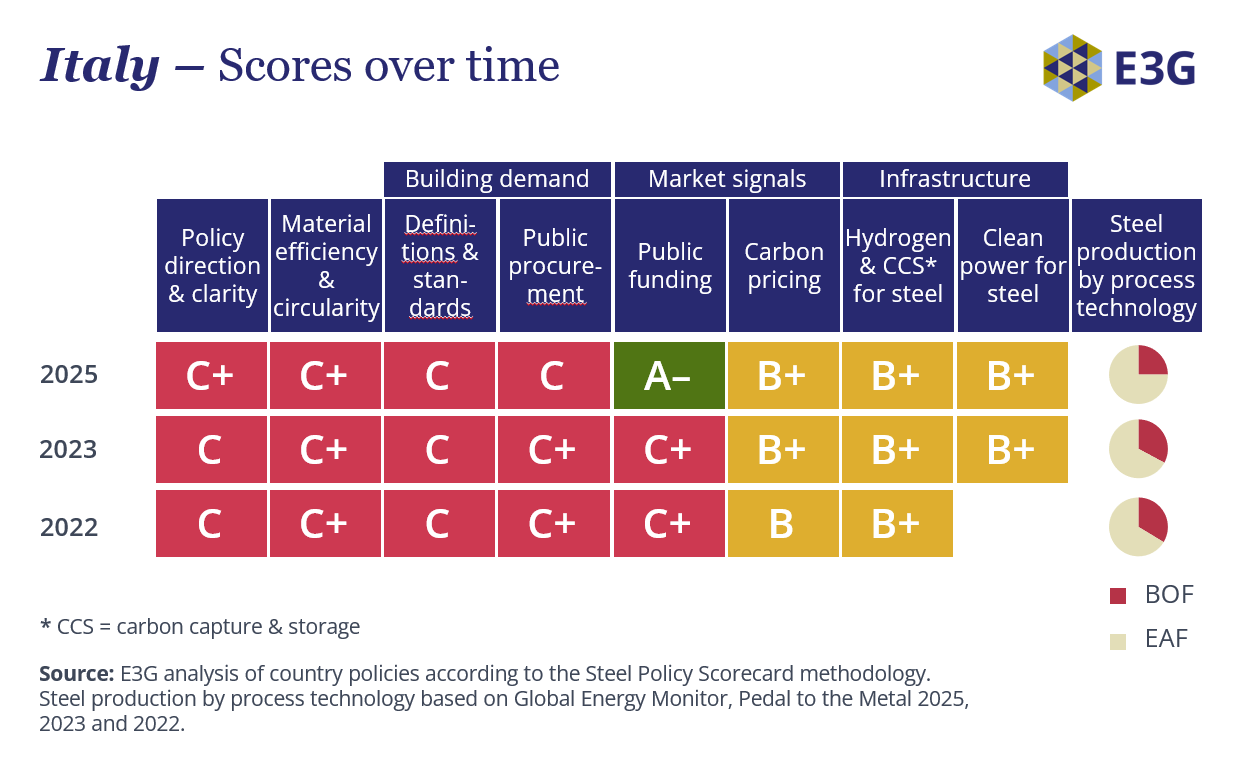

Italy and France are now in third and fourth place respectively. Italy’s score benefited from the partial resolution of the Taranto steelworks crisis, marked by government capital injections and concrete plans for transition. However, while the improvement reflects movement and intent, this does not translate to long-term plans for the site, or for demand creation.

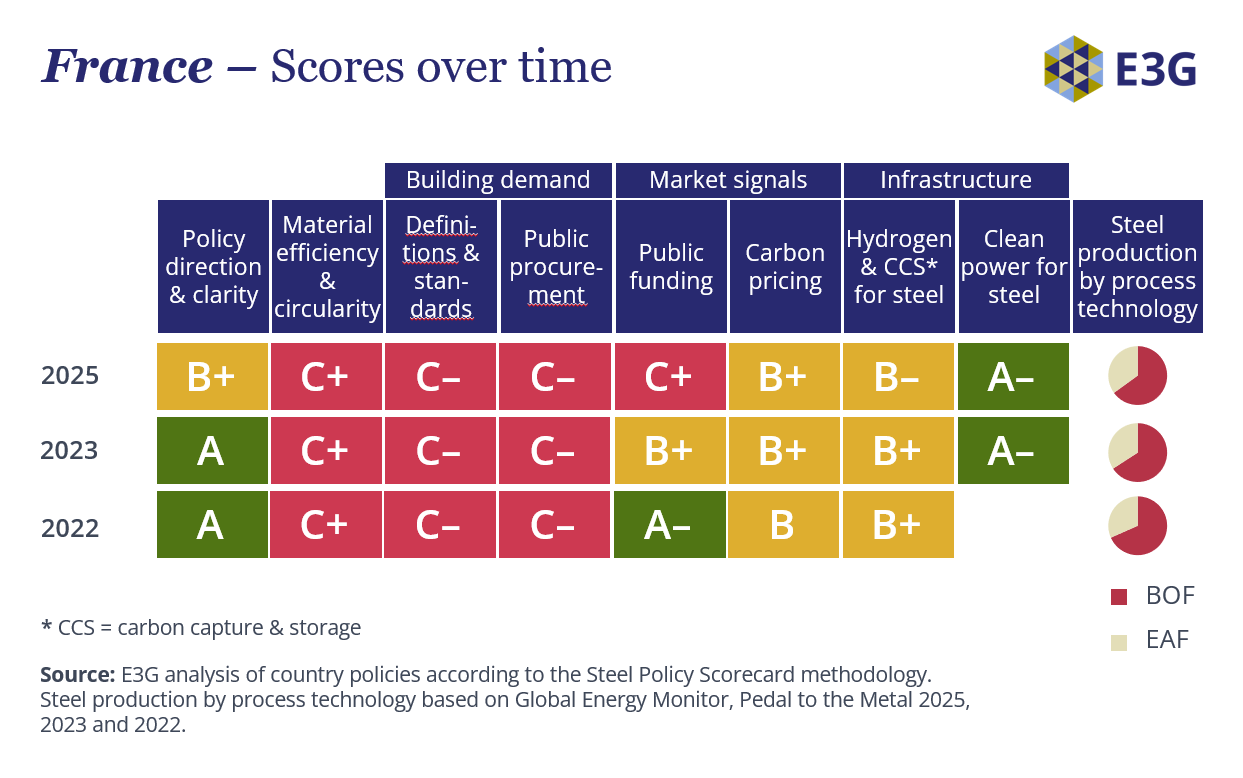

France, on the other hand, has lost some points due to uncertainty over ArcelorMittal’s DRI project – despite the French government’s appeal for more support in the EU’s Steel and Metals Action Plan – with an associated pause in funding and project development. Despite this, the country is at the forefront of industry-related grid updates, having clear plans for renewable energy supply and necessary network capacity upgrades for both of its steel production sites.

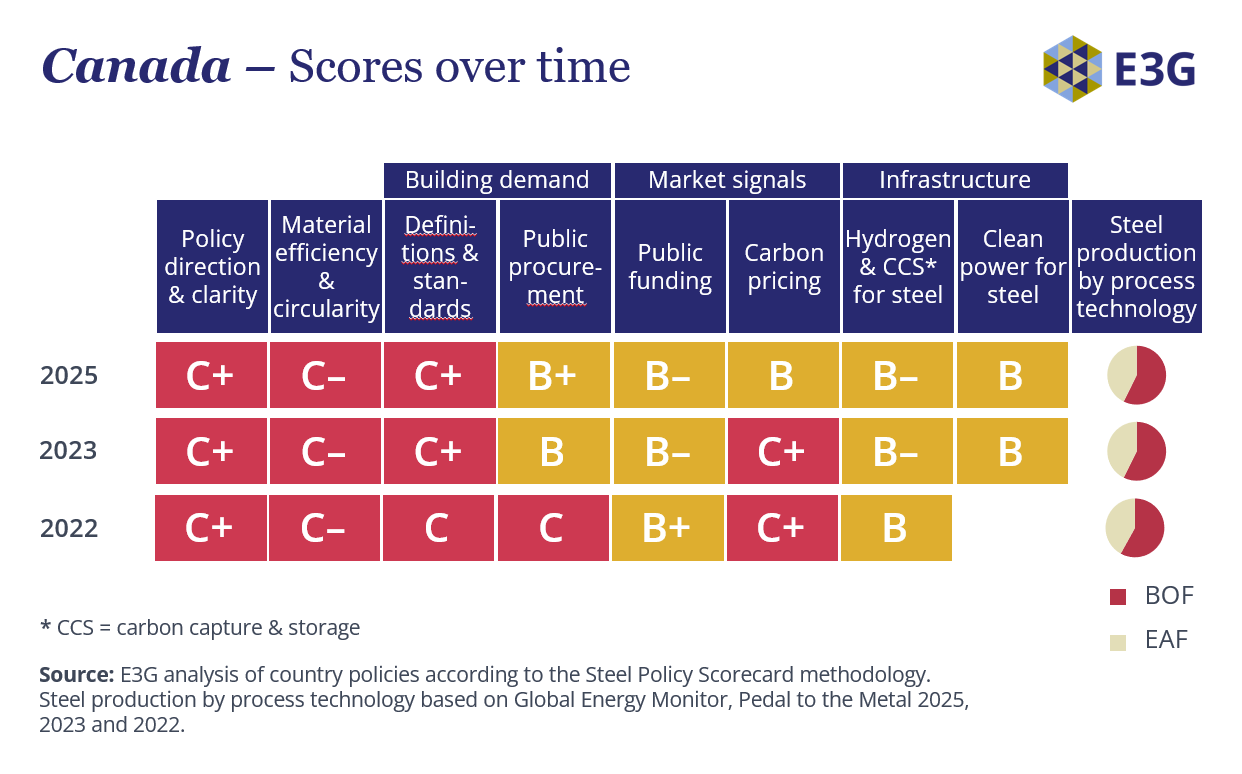

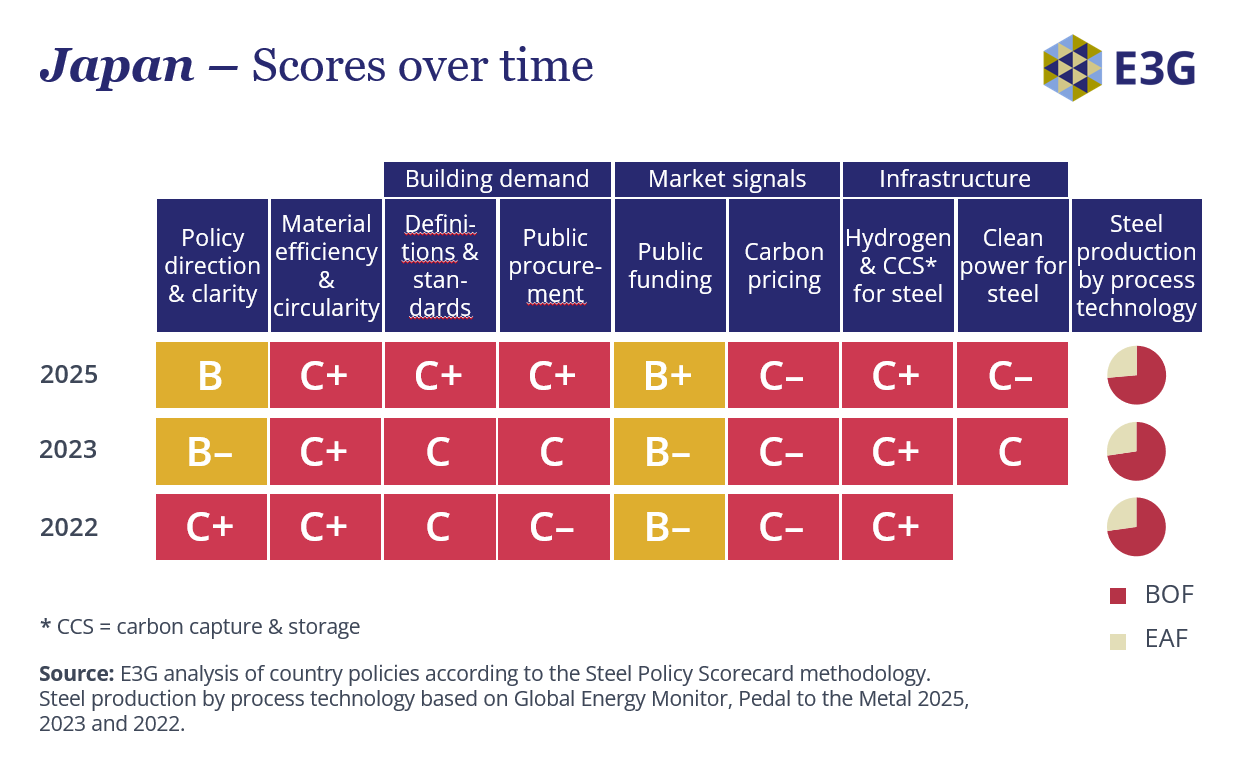

Canada remains in fifth position, followed by Japan with a similar set of scores to previous years. While Canada’s overall standing is stable, the new government’s focus on an industrial strategy that addresses both climate and competitiveness could unlock greater policy ambition. Japan, meanwhile, has introduced new support for EAF upgrades and is piloting procurement schemes in the auto sector, signalling early steps towards building a domestic green steel market. However, its grids – which power the EAFs – remain largely fossil-fuel-based, in contrast to Canada’s largely carbon neutral electricity mixes in steelmaking regions.

The US has moved to last place, with funding cancelled for industrial decarbonisation projects across the country, steel companies exempted from air quality regulations, and progress rolled back on public procurement. The situation remains dynamic.

Recommendations

2025 marks a pivotal juncture for global steel decarbonisation. While the Scorecard indicates some progress on policy ambition, we are still seeing commitments and pledges rather than the actual legislation needed to accelerate steel decarbonisation across key countries. In some jurisdictions, progress has been rolled back, in others delivery and implementation is lacking. This has had an impact on project timelines and investment appetite. The IEA near-zero emissions steel project tracker has shown no uptick in announcements between H2 2024 and H1 2025 and key projects in Germany and France are facing delays. Overall progress is far too slow and without an increase in policy ambition – particularly on clean energy – the delivery of near-zero emissions steel risks stalling.

We have identified the following 5 priorities to put global steel decarbonisation on track.

1. Clean In: Invest in clean steelmaking

EAFs are now the dominant route for planned steel capacity, helping to cut emissions – especially when coupled with improved scrap sourcing. But to fully decarbonise the sector, a major scale-up of H-DRI is essential. However, public funding for H-DRI remains too scarce, especially in geographies facing an energy cost disadvantage. Governments need to ramp up investments in next-generation clean steel technologies, including operational cost support and public procurement to stimulate demand, ensuring that public finance comes with strong climate and delivery conditions.

2. Dirty Out: Phase out high-carbon steelmaking

The G7 must commit to ending the era of unabated blast furnaces. This means no new permits or public finance for conventional blast furnace projects, and a timeline to stop reinvestment in existing ones. Phase-outs must be planned with long lead times and in accordance with just transition principles, including social dialogue (between unions, companies and governments), financial support and assistance in skills training or work redeployment.

3. Power Up: Deliver clean power for industry

Clean electricity is a foundational enabler of near-zero emissions steel, whether powering EAFs, carbon capture and storage (CCS), or the production of green hydrogen for reducing iron. Governments, utilities and steelmakers must coordinate to integrate steel’s power needs into national energy strategies, accelerate grid investments, and ensure affordable renewable energy if prioritised for major industrial hubs. They should further support energy storage integration and grid fee structures that reward industrial users for flexibility, demand response, and off-peak consumption, helping to integrate variable renewables and lower system costs.

4. Partner Up: Strengthen international collaboration

Decarbonising a globally traded commodity like steel demands shared standards, joint investment, and coordinated action. G7 countries should deepen international cooperation through platforms like the IDDI, Climate Club, and Industrial Transition Accelerator to create larger shared markets for green steel, collaborate on financial and technical assistance to pool resources for larger, commercial-scale projects, and share best practice. They must also address trade tensions and re-engage with China to build trust and unlock aligned action on industrial decarbonisation. One priority area is to improve cooperation on implementation of carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs), for example, technical capacity support for developing countries to implement the monitoring, reporting and verification requirements that will come with CBAM adoption.

5. Optimise: Build green iron corridors

The G7 should use trade and industrial policy to support efficient, low-emissions global supply chains. That includes enabling green iron production in renewable energy-rich countries and facilitating offtake agreements to supply downstream steelmaking hubs. Supporting this international division of labour – while ensuring benefits for both producer and buyer nations – can reduce costs, cut emissions, and enhance global competitiveness.

Download this briefing as a PDF.

Note

The goal of the E3G Steel Policy Scorecard is to provide a framework, year-on-year, for tracking and comparing how G7 countries (and key steel producers outside the G7) are meeting the challenge of phasing out coal use for steel and seizing the opportunity to future-proof their steel industries. The Steel Policy Scorecard tracks public policy development and it does not rank countries according to the emissions intensity of their steel production.

The methodology of the 2025 edition of the Steel Policy Scorecard remains unchanged since 2023, ensuring year-on-year comparability. However, in 2025 we added visualisations of the balance of steel production technologies alongside the main ranking figure to provide real economy context.

The data collection cut-off date for the 2025 Steel Policy Scorecard was 15 May 2025.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation for contributions to the data collection process from Carolina Bedocchi and Giulia Novati (ECCO), Aurélie Brunstein (Réseau Action Climat – France), Jana Elbrecht and Ollie Sheldrick-Moyle (Clean Energy Canada), Uni Lee and Oya Zaimoglu (Ember), Hilary Lewis (IndustriousLabs), Kenta Kubokawa (Transition Asia) and Tilman von Berlepsch (Germanwatch).