This article is part of our series on coal phase out and the G7 in 2021. You can find a full list of articles, along with the backstory of our analysis of G7 coal trends since 2015, here.

Japan has shown promising signs of change in its climate policies since last year. In October 2020, Prime Minister Suga announced Japan would aim for carbon neutrality by 2050. At April’s Leaders Climate Summit, Japan followed up with a strengthened mid-term target of 46-50% emission reductions by 2030 compared to 2013 levels, up from a previous 26%. The pledge is still pending formalisation into Japan’s official NDC contribution.

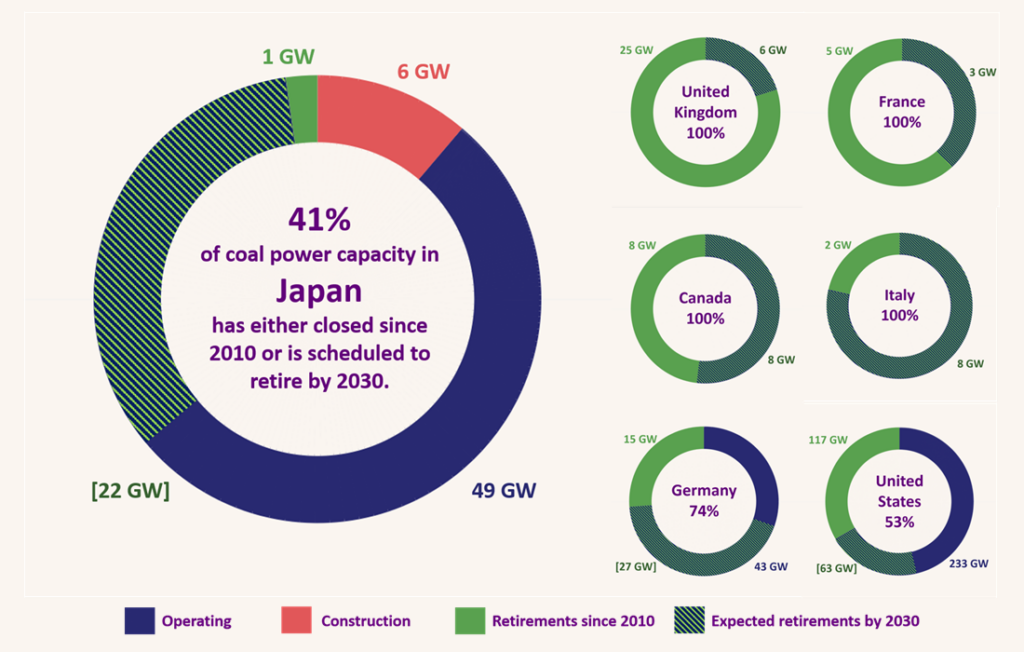

But Japan is now faced with the delivery challenge that its G7 peers have already grasped. Realising this new 2030 climate commitment requires a step change in the power sector, the key source of Japan’s emissions. Some of the country’s power companies have already drawn their conclusions. In April, Japan saw the cancellation of the last two projects in its planning pipeline, meaning no new coal plants are planned in Japan (or anywhere else in the G7). However, Japan’s utility companies still have 6GW of new coal power under construction, a set of ready-made stranded assets that should be abandoned or converted before it is too late.

It is not enough for Japan to move away from plans for new coal. It must now also come to terms with the need to start planning its phase out of coal power generation to meet the 2030 timeframe expected of all OECD countries.

Japan’s path ahead hinges on its national energy strategy review. This is currently underway with a first draft expected in the very near future. Until recently, signs from the administration raised concerns as to whether the revised energy policy will adequately support Japan’s climate targets. Approximately 40% of power in 2030 is predicted to be sourced from coal and LNG. A recent government sub-committee’s proposal (in Japanese) shows the administration is considering new efficiency target levels for the existing coal fleet. This is prompting utilities to choose between closing their least efficient units, co-firing biomass or other fuels with coal, or technical improvements to reach 43% efficiency standard by 2030. This could drive up costs and weaken the plants’ competitiveness against alternatives, helping to the fill a gap left by the absence of effective carbon pricing.

However, it appears that elements of the government and bureaucracy are still attached to Japan’s ‘efficient’ coal technology paradigm, which ignores lifetime emissions and allows coal plants to operate beyond 2030.

To align with G7 peers, Japan could accelerate and expand last year’s policy announcement to phase out less efficient coal units by 2030, expected to result in approximately 100 units closing. The energy strategy review should build on this and develop scenarios that lead to Japan phasing out its entire coal fleet by 2030. Figure 1 highlights that Japan has only seen approximately 1GW of capacity close since 2010 and that its current plans would only see 41% retired by 2030.

Helpfully, a push for accelerated decarbonisation is growing in Japan’s progressive business community and at subnational level too. Kyoto has recently joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance, and is advocating for utility company Kansai Electric to shift to a carbon emission-free power supply system as soon as possible. Similarly, Tokyo has set a notable target to use 50% renewably generated electricity by 2030.

Japan needs to end its international coal finance

More is also expected from Japan in terms of its international contribution to decarbonisation. Though Japan made a commitment in 2020 to restrict public overseas coal finance in principle, it left open the opportunity to support ‘high-efficiency’ projects based on host country circumstances. Currently, Japan still is believed to be considering support for two coal power projects, Indramayu in Indonesia and Matarbari 2 in Bangladesh.

Japan is now under pressure to join with the rest of the G7 in announcing an end to public finance for coal. Four recent developments could help push it in the right direction:

- Peer pressure from near neighbours. The recent announcement that South Korea will end coal finance leaves Japan and China as the last major countries left publicly supporting coal. China has already indicated it will not support further coal power projects in Bangladesh.

- Private sector progress. Japan’s major financial institutions and trading houses have continued to set increasingly strong restrictions on further participation in new coal power projects or expansion of existing power plants. In May 2021, SMBC joined Japan’s other megabanks by ending a previous exemption that allowed financing of ‘efficient’ ultra-supercritical coal plants. The government should take the opportunity to show leadership by extending the public financing restriction to all new coal plants, regardless of technological fine print.

- Regional rethink. The Asian Development Bank’s new draft energy policy rules out further finance to coal power and heat. Moreover, it commits to support its member countries to “achieve a planned and rapid phase-out of coal in the Asia and Pacific region”. Japan is ADB’s biggest shareholder and a major influence. Aligning with this regional approach would provide a coordinated tack away from coal.

- Major power influence. The US-Japan Climate Partnership, agreed during PM Suga’s recent bilateral with President Biden, includes the following commitment. “Japan and the United States will align official international financing with the global achievement of net zero greenhouse gas emissions no later than 2050 and deep emission reductions in the 2020s, and will work to promote the flow of public and private capital toward climate-aligned investments and away from high-carbon investments”.

All these developments make the time ripe for Japan to commit to end overseas coal finance.

Speaking at the Leaders Climate Summit this April, Prime Minister Suga emphasised Japan “is determined to take the lead in solving the challenge of climate change for the whole of humankind”. To deliver on that promise, Japan should stop searching for loopholes and recognise that the coal era is coming to an end. It should seize the 2021 moment to finally join with its G7 counterparts in delivering this step change.

Jump to another article in this series:

- Charting the course away from coal: the G7’s leadership opportunity

- Strong currents: G7 coal transition data trends

- Surfing the waves: G7 progress towards coal phaseout

- Picking up the pace: Germany’s coal exit is getting closer to 2030

- Anchors aweigh: USA rejoins the coal transition mainstream

- Time and tide wait for no one: Japan’s coal progress