With Germany slipping from its position as a climate leader, an industry with just 20,000 jobs is dictating policy to the federal government

The German energy transition has long been seen as one of the world’s most ambitious and effective undertakings in the fight against climate change, and the country has widely been praised as a climate leader.

And Germany has indeed achieved significant progress: public and private investments in renewables have helped drive down costs of clean technologies and the share of renewables in the country’s electricity mix has quickly grown to over 40%.

Recently, however, German climate policy has been subject to international criticism. Former US vice-president Al Gore has warned Germany risks being “left behind” as other countries outpace the former energy transition leader.

He is right. Germany will fall far short of its 2020 emission reduction targets and it is unclear how the country will reach its goals for 2030. The large share of dirty lignite coal in the country’s electricity mix, coupled with continuously high emissions from agriculture and transport, make it impossible for Germany to meet its national and international climate obligations.

If Germany is to honour its obligations, a timely coal phaseout is a crucial step. A recent analysis by WWF showed that, given the goals of the Paris Agreement, the remaining German emission budget for the energy sector alone would be completely used up if all currently available lignite reserves were burned.

A few weeks ago, the country took a first, cautious step towards a coal-free future. At the end of June, the so-called Coal Commission began its work. The body brings together experts from civil society, politics, academia and the real economy with the aim of drafting a plan for the coal phase-out.

The ministry of the economy, which is charged with coordinating the commission’s work, has given it a clear mandate: saving jobs in the coal sector is its first priority, followed by designing the structural change in the coal regions towards low-carbon economies, with climate protection and coal phase-out coming last. An analysis by think-tank E3G has shown that this focus on the employment consequences of moving beyond coal will most likely lead to a phase-out date that is well beyond the timeline required by the Paris Agreement – inevitably bringing up the question why jobs in the coal sector are so politically charged in the first place.

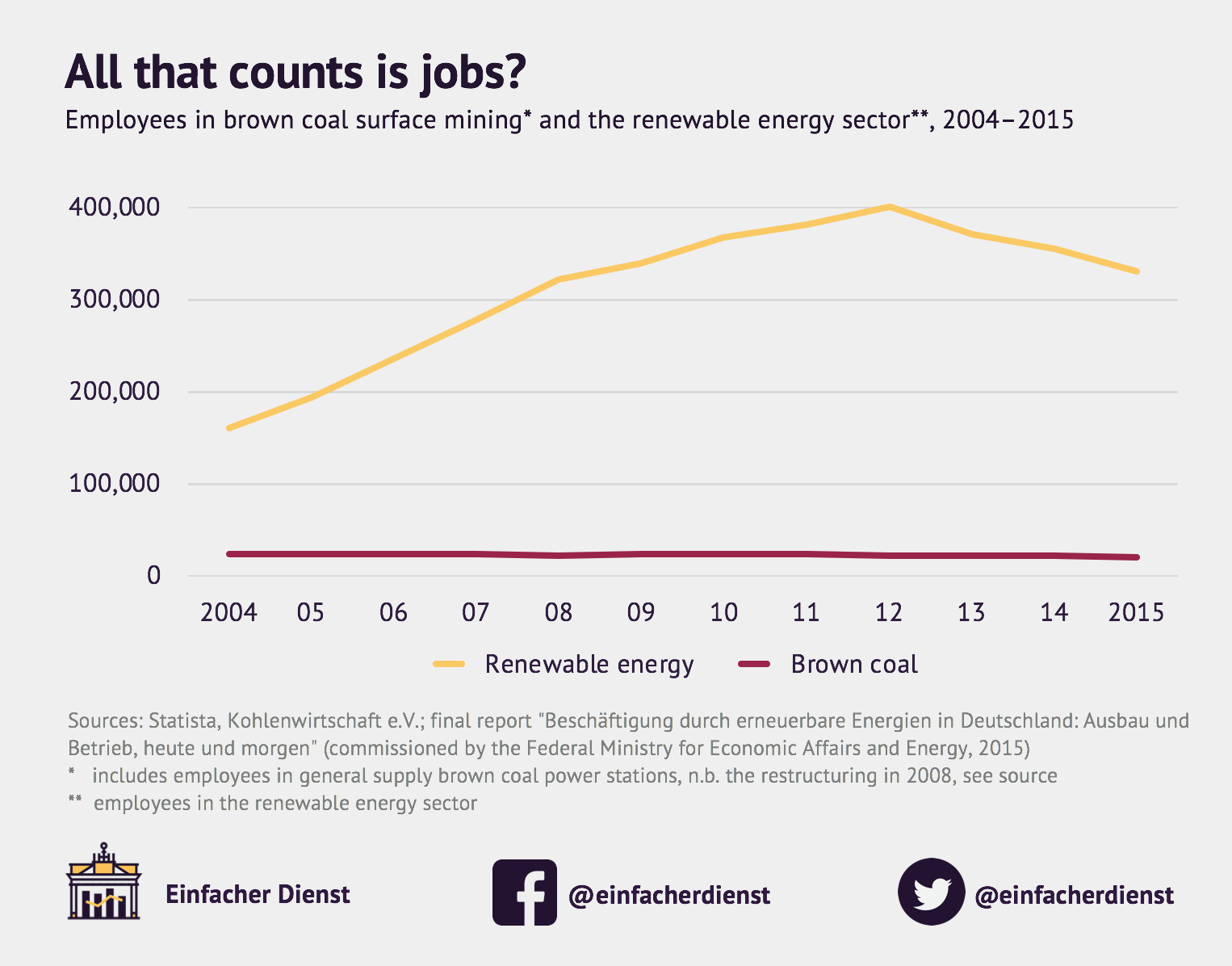

A first thought might be that, as is the case in Poland, coal jobs are simply so numerous that an early coal phase-out would be extremely disruptive. Comparing the employment levels of the coal sector with those of renewables shows that this is not the case: today, the German coal sector employs roughly 20,000 people, compared to the 330,000 people employed in renewables. Even more notable is that more than 50,000 jobs were lost in the renewables sector since 2012 – far more than would be threatened by a transition away from coal. Those cutbacks were actively caused by the federal government in 2012 through an energy policy devised to rein in the growth in renewable energy.

Another prominent topic in the coal debate concerns the required structural change, known as ‘just transition’, from high-carbon to low-carbon regions. Central to a just phase-out plan needs to be a strategy for how to transition former coal regions into regions that are fit for a low-carbon future. Many proponents of coal worry that such a transition will be impossible in the near future, and that an early phase-out would hit the affected regions badly.

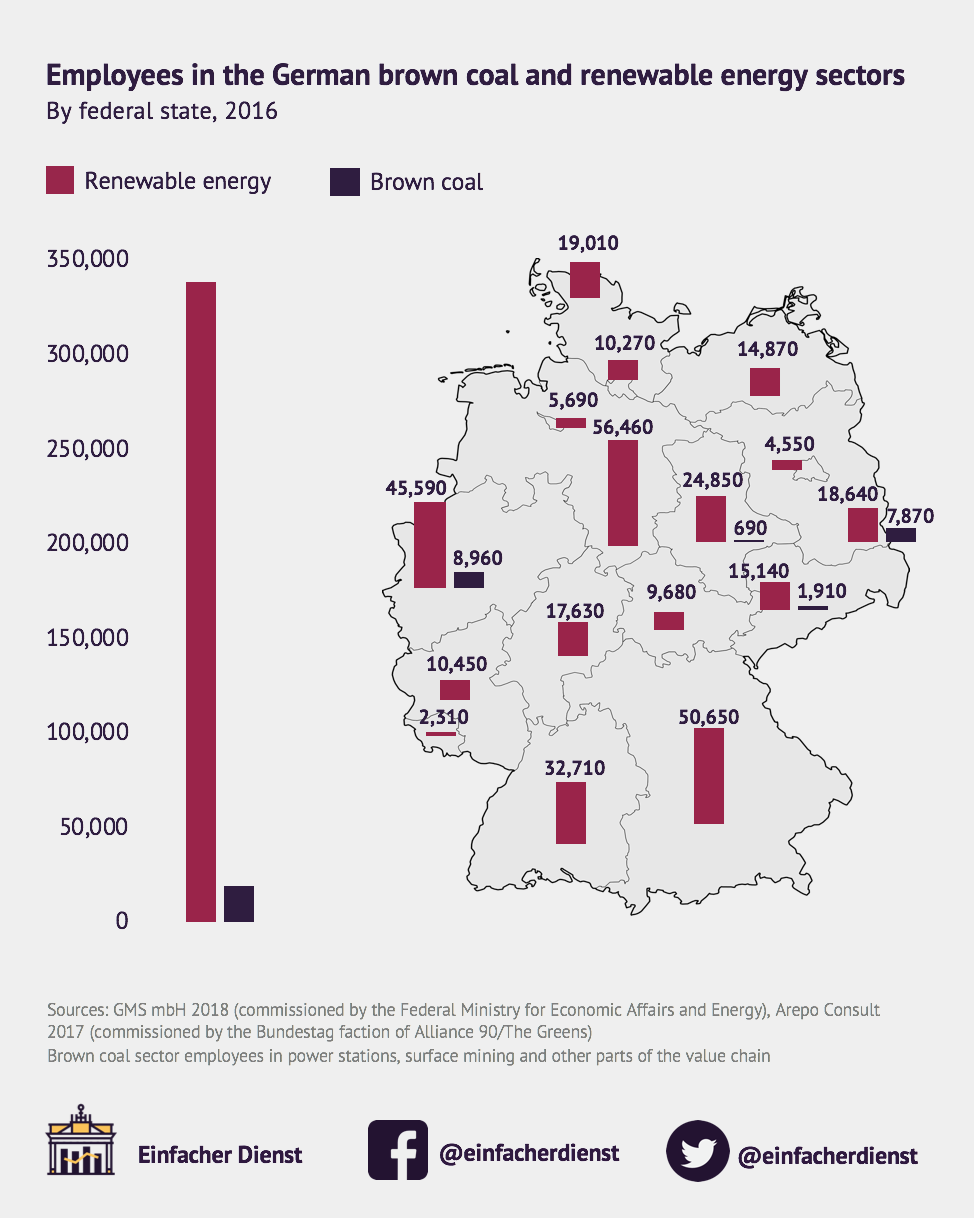

A comparison of the employment importance of coal and renewables in the German federal states shows, however, that renewables already employ many more people in every federal state – including in the traditional coal states. Another relevant insight comes from the Federal Environment Agency, which has recently calculated that almost two thirds of those employed in the coal sector will go into retirement by 2030 due to the sector’s ageing workforce and that the climate targets for 2030 could thus be met without any additional lay-offs. A just and well-planned coal phase-out would therefore be possible without any significant harmful effects on the lives of those currently working in the coal sector.

Furthermore, the indirect employment effects of coal, which are often cited as another major hurdle, are also limited. Even in the often mentioned structurally-weak coal region Lusatia in the country’s east only 3.3% of jobs are directly or indirectly dependent on the coal sector. All this shows the challenge posed by employment in coal is significantly smaller than it’s often being presented, particularly in light of the federal government’s guarantee of providing at least 1.5 billion euros for the coal regions’ transition.

A few other reasons seem to contribute to the nonetheless prominent role of coal jobs in the political debate on energy and climate. Firstly, around 80% of coal workers are union members, making them considerably better organised than workers in renewables. Also, it is undeniable that coal energy companies have a strong economic interest in making as much profit as possible with their written-off facilities, and often use the fate of coal workers for political leverage.

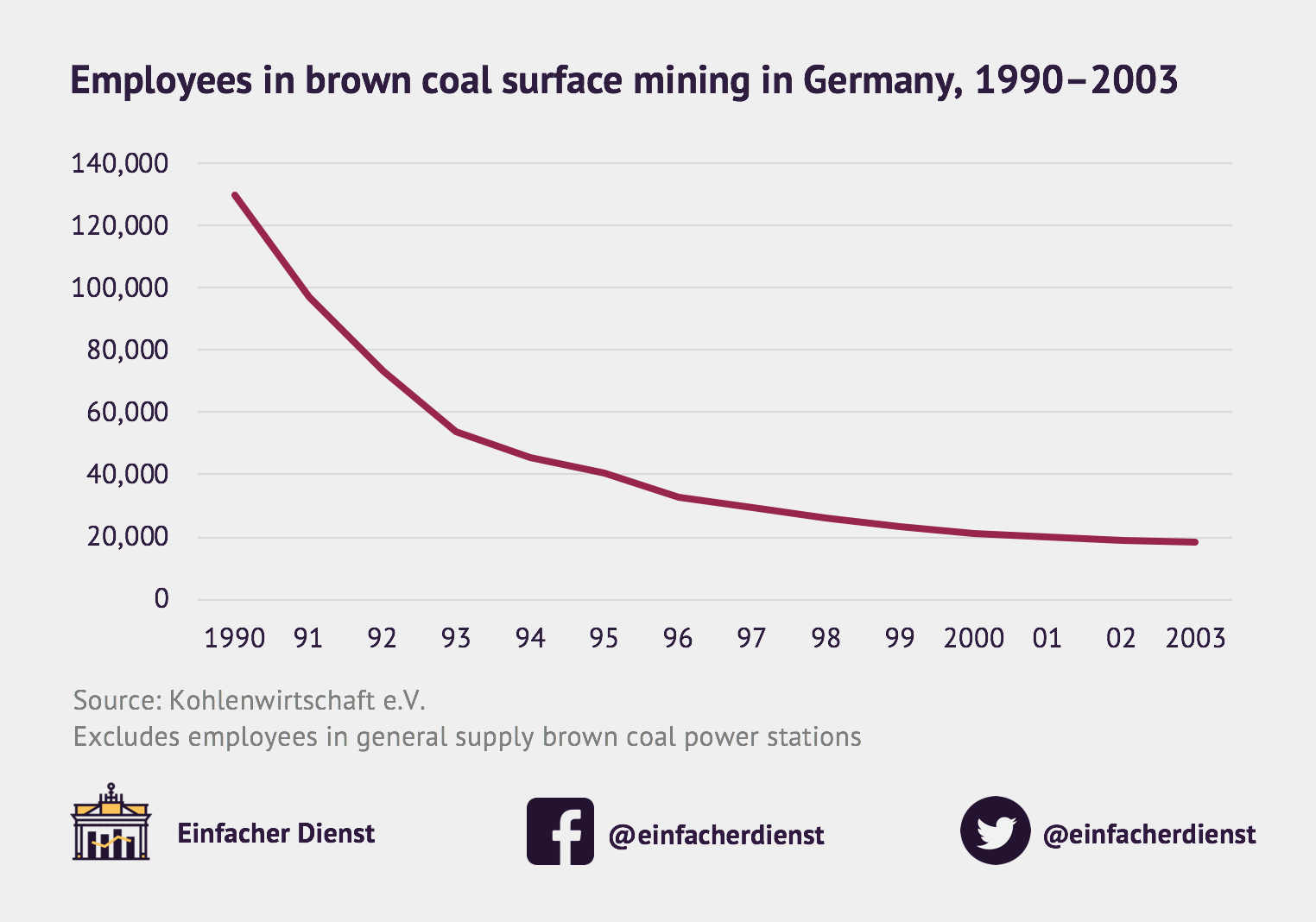

Ultimately, a certain nostalgia may also play a role, centred around the lignite that fired up the German ‘Wirtschaftswunder’ (economic miracle) in the post-WWII years. And, lastly, it is important to recognize that many of those living and working in the coal regions especially in eastern Germany are still carrying some scars from the dramatic structural break that took place there during the 1990s. Within a few years, the numbers of jobs in coal mining alone dropped from 110,000 to 10,000, and the total number of coal jobs dropped from 130,000 to 23,000.

That dramatic historical development was poorly managed and should not repeat itself. But the upcoming transition in German coal regions is already better prepared and renewables have already overtaken coal; not only with regards to the number of jobs created, also in terms of their costs and the amount of electricity generated.

The members of Germany’s Coal Commission are facing an important task and must set the right priorities in an emotional debate. They have to find a plan that guarantees a secure future – both for global stability in face of climate change and for those employed in the coal sector. This analysis strongly suggests that the best way to chart such a plan is to focus on the jobs of the future rather than on the jobs of the past – especially in light of Germany’s pressing climate commitments.

This article was originally published in German on Einfacher Dienst.