E3G’s Political Economy Mapping Methodology (PEMM) assesses threats and opportunities to countries presented by the low-carbon transition. PEMM aims to identify underlying tensions across national conditions, political system and external projection to determine what constructs a country’s core national interest and to identify key interventions which could help to increase domestic climate ambition and enable progress on the low-carbon transition. PEMM is based on desk-based research, expert interviews and in-country testing.

Our assessment of Bulgaria shows clearly that many aspects of the country’s political economy stand in opposition to a low-carbon transition. In all three headline categories of our analysis – national conditions, political system, and external projection – we conclude that most factors actively oppose the transition. Nevertheless, we have identified several access points for an accelerated low-carbon transition in Bulgaria:

National Conditions

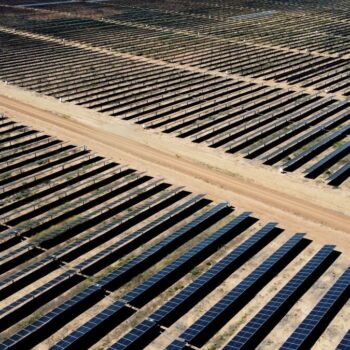

Overall, the national conditions oppose an accelerated low-carbon transition. In particular the salient debates on energy prices, incumbent energy producers and energy security stand in sharp contrast to a move away from fossil fuels. Energy is a highly political issue in Bulgaria, and coal accounts for almost half of the electricity mix. Nuclear power provides another third of electricity, and the construction of new nuclear power plants is under discussion. In addition, inefficient energy infrastructure, high concentration of ownership in the energy sector, close ties of incumbent businesses and politics, and energy poverty are perceived as key issues for the country. Despite high economic pressure on coal Bulgaria has not yet defined a phase-out date or a Just Transition strategy. After a generous support scheme for renewables had fostered growth, recent cutbacks and new regulatory roadblocks have quasi-ended the deployment of renewable technologies. Other sectors, particularly transport, are not yet ready for more ambitious emission reduction targets that should be expected in the future. Existing targets for renewables and emission reductions in the non-ETS sectors will, however, be met. While import dependence in the energy sector is below EU average, driven by domestic coal and the recent expansion of renewables, it is a major issue for imports of gas, oil and nuclear fuel, mainly from Russia. Lower dependence is hindered by missing energy infrastructure, and Russia’s role as guarantor of energy security has significant implications for foreign policy. There is huge potential for additional wind and solar capacity across the country.

Potential drivers of the low-carbon transition such as technology, innovation, finance and the perception and role of public goods are not yet playing a relevant role in Bulgaria’s transition. Nonetheless, Bulgaria is a regional leader in outsourced digital services which is a well-paid high-growth sector in cities. Low investments in R&D, brain drain, demographic decline and a lack of skilled workforce in many areas are, however, key challenges for further technological development. The boom in renewables has shown that Bulgaria could benefit from active engagement in low-carbon supply chains. This would, however, require targeted public investment. While overall macroeconomic factors are relatively positive and stable, and poverty reduction is progressing at a modest pace, investments in a low-carbon transition are largely dependent on the EU budget. Significant investment gaps in renewables, energy efficiency and low-carbon transport persist. While climate change is not perceived as a key challenge for the country by the public, more tangible environmental issues are of public concern. In particular, air pollution and the protection of Bulgarian national parks are discussed widely. In addition, while Bulgaria has a relatively low risk of natural disasters, it is one of the EU countries most vulnerable to climate impacts, and economic costs are rising.

Political System

Overall, key actors and institutions of the political system oppose an accelerated low-carbon transition. Government and businesses tend to support incumbent high-carbon industries. Government policies are centred around the office of the Prime Minister. However, the involvement of a nationalist party in the current government has changed the public discourse, placing a stronger focus on “illiberal” issues such as migration. Overall, trust in domestic political institutions is relatively low, and corruption is identified as a systemic challenge, including in the energy sector. Close ties between politicians and incumbent businesses, in combination with a lack of administrative capabilities in government, cause difficulties for implementing long-term policies and measures.

The service sector is at the core of the current economy, and its importance is growing. Heavy industry played a crucial role in socialist times but is in continuous decline. While the importance of state-owned companies is generally limited, after a wave of privatization, it is quite significant in the energy sector, blocking further market liberalization.

The quality of public debate and press freedom in Bulgaria are under pressure, and civil society has relatively limited access to political decision-making, in which climate politics, in contrast to energy politics, receives very limited attention. Participation in civil society organisations is low; however, public opinion of environmental groups is relatively positive as they are perceived as one of the few stakeholders speaking out against structural ties between politics and incumbent businesses.

EU accession in 2007 provided an impetus for political and economic reforms, and the EU remains the key driver of environmental and climate legislation in Bulgaria. However, the country plays a reactive role at the EU level, and overall lacks the resources and political influence to advance its political interests in Brussels. Membership of the Schengen area and the Eurozone are foreign policy priorities but have been blocked by other member states.

External projection and choice

Western countries are important partners for Bulgaria, mainly due to their impact on the country’s economic development. At the same time, energy supply and historical links connect Bulgaria to Russia. The European integration of the Western Balkan countries is Bulgaria’s primary foreign policy priority, and most Bulgarian governments have continuously advocated for improved economic cooperation in South East Europe. One of the most important components of such cooperation is the development of transport and, increasingly, nuclear and fossil energy infrastructure, creating risks of high-carbon lock-in. Bulgaria is not an active climate diplomacy player but has spoken out against more ambitious climate targets both in UNFCCC negotiations and within the EU.

You can read the full report, The political economy of the low carbon transition: climate and energy snapshot: Bulgaria, here.