Policymakers are increasingly adding elaborate caveats to energy transition pledges in an effort to look ambitious on climate action, while refusing to fully engage with the implications of net-zero emissions for natural gas, writes energy analyst Jonathan Gaventa.

In an awkward 64-word sentence littered with caveats, G7 environment ministers last week committed to “phase out new direct government support for carbon intensive international fossil fuel energy”.

The pledge is the latest of a series of commitments from governments and international institutions on phasing out public financing for fossil fuels to align with Paris Agreement goals. However, the convoluted phrasing is a sign of the increasingly bitter disagreements taking place behind the scenes about continued financing for natural gas, particularly in low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

These disputes raise important issues about global equity and justice in the energy transition, the imperative of delivering energy access, the economics of gas and renewables investments in low income economies, and the risks of stranded fossil fuel assets.

By adopting vague language and non-transparent caveats, governments and financial institutions are obfuscating these questions rather than addressing them. Ultimately, they risk confusing, rather than accelerating, the transition to sustainable development.

Commitments and caveats

Governments finance fossil fuels internationally through a variety of channels. These include bilateral overseas development aid, export credit finance linked to trade, and lending through national development banks. They also include financing via multilateral development banks such as the World Bank or the African Development Bank.

In 2015, the Paris Agreement set an explicit goal to shift financial flows to make them consistent with low-emission development. Ahead of the COP26 climate summit later this year, governments and financial institutions are issuing a cascade of commitments to demonstrate they are bringing financing policies in line with Paris commitments.

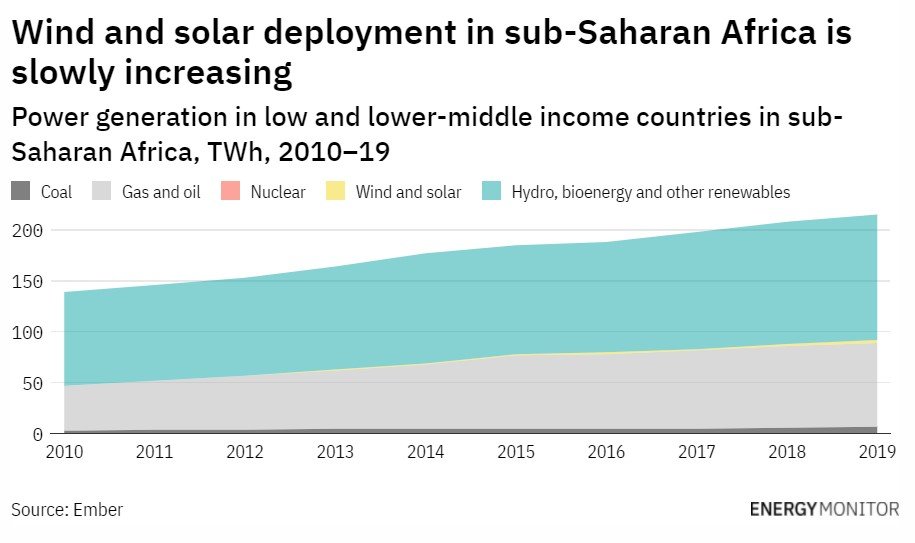

Far from operating as a backup to renewables, oil and gas are the fastest-growing source of power generation in low and lower-middle income countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

At the Finance in Common summit last year, a “joint declaration of all public development banks in the world” committed to align activities with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Earlier this year, seven European countries committed to end export credit financing for coal and assess how to phase out other fossil financing.

In a wide-ranging commitment, the UK decided last year to end all “direct government support for the fossil fuel energy sector overseas”. The US followed with a similar but vaguer pledge towards the energy transition this year.

Coal is clearly on the way out, according to these pledges. The G7 statement commits to an end to coal financing by the end of 2021. South Korea, long a holdout, committed to end coal financing earlier this year. That leaves China as the lender of last resort for new coal.

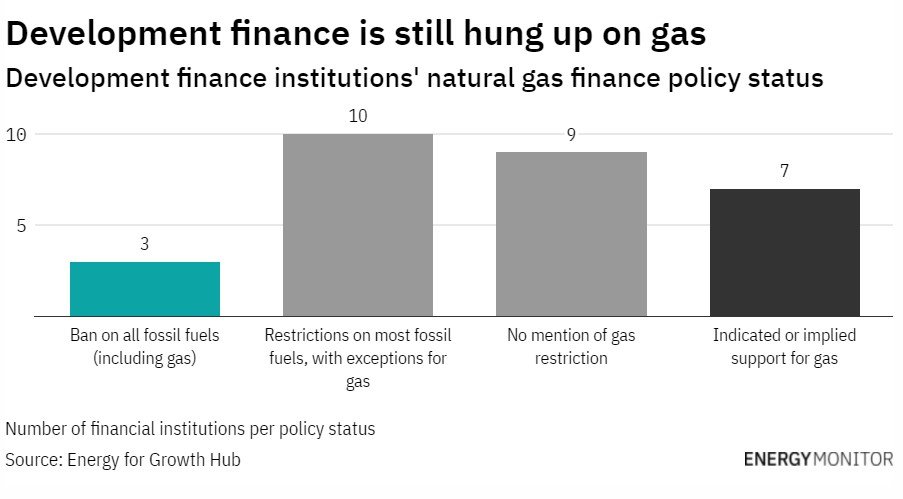

Again and again, however, these commitments stumble over the issue of finance for natural gas. Most development finance institutions committed to the energy transition and phasing out fossil finance have left some wriggle room for continuing to finance gas. These caveats and exemptions are increasingly elaborate, ranging from broad language on consistency with net zero and national Paris Agreement commitments to exceptions for the poorest countries.

The gas stumbling block

Natural gas projects are major recipients of international public finance for energy. Analysis of energy financing from the world’s largest governments and multilateral development banks shows that between 2013 and 2018 fossil fuels received three times more public financing than renewable energy, with gas as the largest beneficiary.

In a particularly notable example, export credit agencies and the African Development Bank recently provided $13.8bn in project financing to the now-troubled Mozambique LNG project – over 50 times more than the $245m in international financing dedicated to renewables support programmes.

While governments and financial institutions are beginning to increase investments in renewable energy projects in Africa, they are far from a breakthrough on renewables in Africa. Over the last ten years, only 2% of renewable generation capacity globally was installed in Africa. In 2019, Italy alone produced more solar power output than the whole of Africa.

Far from operating as a backup to renewables, oil and gas are the fastest-growing source of power generation in low and lower-middle income countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Since 2010, oil and gas generation has expanded 12 times more than wind and solar.

Moral arguments

Much of the argument around retaining international public finance for gas is framed in moral terms. Some commentators claim it is hypocritical for rich countries – which already have fossil fuels dominating their power mix – to deny poorer countries the same opportunities. Sub-Saharan African countries have low historic responsibility for climate change, and doubling or even tripling the low levels of electricity use in low-income sub-Saharan African countries using gas would add only a small amount to global emissions.

On the other side, campaigners argue it is hypocritical for rich countries to continue to finance fossil fuels abroad while phasing them out at home, especially given the harm they can present to local communities.

In this framing, rather than funding new gas, addressing the climate debt of industrialised countries should mean radically scaling up support for clean development pathways – commitments that remain unmet.

Meanwhile, the International EnergyAgency (IEA)’s net-zero pathway shows no new gas fields should be approved for development anywhere in the world, which means new investments could become stranded assets. In this pathway, developing countries move to net-zero power systems by 2040 – well within the lifetime of new combined cycle gas turbines investments, which can last 25–30 years. While the IEA pathway does not preclude some investment in gas resources in low-income countries, it is clear the potential for new gas investments is limited.

Energy for development

A second issue at stake is energy access. In sub-Saharan Africa, 580 million people remain without reliable modern electricity, and countries have committed to reaching universal energy access by 2030 as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Developing new LNG projects for export does not address this energy access challenge directly. New power plants such as gas facilities can play a role in addressing energy access where a shortage of electricity generation is the key bottleneck.

For most countries with low levels of energy access, however, the key gap is not power generation shortage, but a lack of access to transmission and distribution networks, especially in rural areas. Grid expansion and decentralised renewables are better options for energy access rather than investing in new gas power plants.

Grid expansion and decentralised renewables are better options for energy access rather than investing in new gas power plants.

Off-grid solar and mini-grids are particularly important for providing basic energy services to remote areas. However, only 1–2% of international public finance for electricity in Africa flows to distributed renewable energy.

A further area of dispute is the role of gas in economic development.

Gas is framed as an enabler of industrialisation, as a raw material for industry and as a source of power generation. However, the changing economics of power systems are beginning to shift this storyline as renewables become the cheapest form of new power generation across the world. Over-building gas generation presents economic risks including higher and more volatile energy costs, adding to debt strain and reducing the economic competitiveness of the region.

In some African countries, take-or-pay gas supply contracts intended to enable gas power generation have proven to be economically disastrous when the contracted volumes of gas turned out to be unnecessary.

Backing up renewables

A final line of argument for gas exemptions is around the role of gas in backing up variable renewables such as wind and solar. Flexibility resources are needed for a high-renewables power system to operate, particularly in countries with weak transmission and distribution grids.

However, most gas power investment in low-income countries in Africa is for combined-cycle gas turbines that run as baseload. Peaking plants that operate solely to back up renewables are seen as economically unviable.

As a result, new gas investment can freeze out renewables from the market, rather than enabling it. In countries without competitive power markets, new gas power often comes with inflexible, long-term contracts that crowd out cheaper renewable power generation rather than acting as a complement to wind and solar resources.

Clarity or confusion?

The problem with the vague caveats on natural gas being adopted by governments and international institutions is that they offer little guidance to project developers, African countries or citizens about what kind of projects will ultimately be financed. It is often unclear whether the pledges will permit business-as-usual financing for gas or whether gas investments will be curtailed. They neither lean in to a predominantly renewables energy transition and development pathway, nor do they own up to rejecting it. A key test for any new pledge must be whether it creates clarity or confusion.

Time is running out for meeting the Sustainable Development Goal of universal energy access by 2030 and the Paris Agreement aim to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Governments and financial institutions need to tell a clearer story of how they will shift financial flows from fossil to clean, meet commitments on climate finance for developing countries, deliver a just transition and support a massive scaling up of renewable energy investment to meet growing energy needs in sub-Saharan Africa.

This article was originally published by Energy Monitor.