In the context of Coronavirus and climate, Tom Burke sets out the battle-lines in the conflict over the planet’s future – between policy and politics, cooperation and competition, young and old, freedom to and freedom from.

Ever since the arrival of the Coronavirus pandemic, we have all struggled through a fog of uncertainty to rebuild some future we recognise. But, just as this fog shows signs of beginning to clear, another deeper and darker fog is descending on the future.

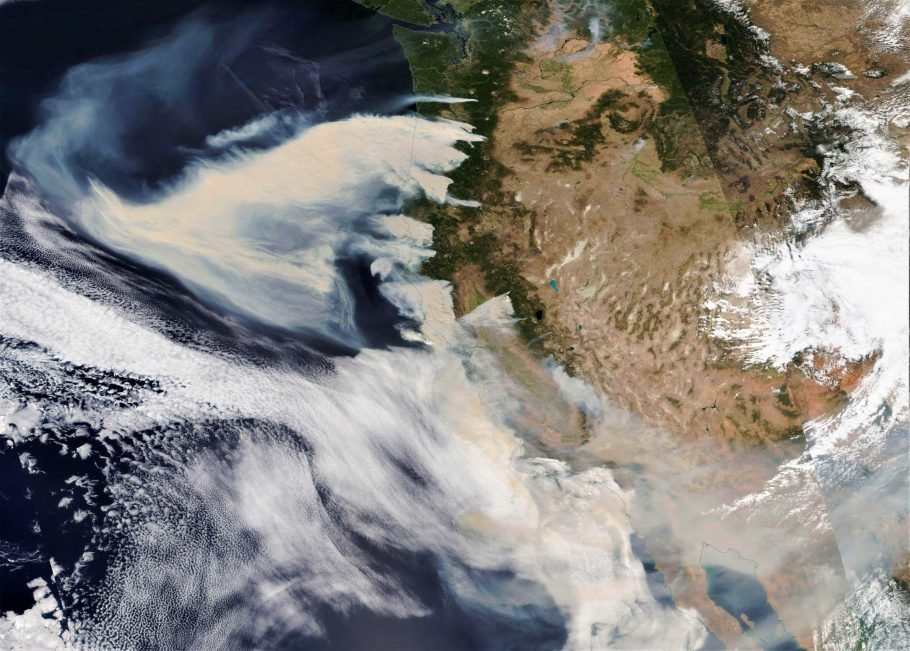

The unprecedented, though not unexpected, outbreak of simultaneous floods, fires, and droughts in every part of the planet tells us that climate change is here now. It is cancelling futures more powerfully and methodically than Coronavirus or any ‘culture war’.

The visible political battle to shape the future is already underway – a battle between familiar conflicting interests and ideologies. There is a deep desire on the part of today’s politicians to return to yesterday’s comfortable contests.

But there is an altogether different, less visible and much more important battle emerging within the fog: a battle over the political ideas and narratives that will shape the history now in flux.

The policy ideas that make up the daily matter of political discourse are not the same as political ideas. Policy ideas reveal what a party promises to do; political ideas explain why.

Current political debate focuses almost exclusively on policy ideas. Parties set out a smorgasbord of policies to attract voters and there is only rarely a discussion of the political ideas that underlie them – the ideas we use to make the deeper choices about how we organise our societies. They have little value in today’s politics and are seen as a distraction, irrelevant to the task of seducing voters with intensively focus-grouped policy enticements.

The Coronavirus pandemic has disrupted this comfortable collusion. The psychological shock of the abrupt cancellation of everyday habits will not quickly fade – personal experience leaves a deeper mark in the memory than an encyclopaedia of facts. And it is already validating the warnings from climate scientists and shaking our confidence in the future.

As we rebuild our lives in the wake of the Coronavirus, the questions of how, and to what purpose we rebuild are emerging. The less visible battle over political ideas will matter more than that over policy programmes.

It will be a battle on four fronts.

The Battle Fronts

The first front has come into focus over the lifting of restrictions during the pandemic. This is the battle between freedom from and freedom to. The protestors opposing pandemic lockdowns defended their freedom to leave their homes, while those arguing to keep the lockdowns were defending their freedom from infection with a deadly disease.

Freedom of choice has become a dominant policy purpose in recent decades – but freedom to is bought at the price of freedom from. Is my freedom from a climate I cannot live with more or less important than your freedom to burn fossil fuels? If climate policy fails, will the consequent social and political disruption mean that no one is free in either mode? Who should decide and with what legitimacy?

The second front is the battle between competition and cooperation as a fundamental organising principle of our political economy. The dominance of cooperative over competitive responses established in the aftermath of World War Two has been eroded and competition has been the dominant note for the past 40 years. This is true both within nations and between them. The consequence has been a progressive loss of social cohesion as inequality has grown. None of the pressing global problems of the 21st Century – climate change, novel pathogens, international terrorism, people trafficking – can be successfully tackled unless we can relocate competitive forces within an envelope of cooperation.

The third front is a battle between knowledge and belief as the operational foundation for political decisions. Should what I know to be true or what I believe to be true define the choices that we must make? Our failure to make the promise of prosperity authentic for all has undermined confidence in knowledge as the basis for political judgement. If knowledge does not actually make things better, belief can at least make me feel better. Accelerating change is discomforting and makes belonging matter more.

The fourth front is the battle between the political ideas of the incumbents and those of the inheritors. Incumbents are those who were comfortable with the way the world was before – when they had power, affluence and influence – and they would like it restored. The inheritors are those for whom the future was increasingly constrained by inequality and the breaching of planetary boundaries. They wish to build a new and different future that is socially and environmentally just. The incumbents are older; the inheritors younger.

Climate change means that we must decide what kind of future we want or let the climate decide it for us. This is a prospect that fills some of us with hope and others with fear. In choosing our political leaders, we must choose carefully between those who will seek to divide us with fear or unite us with hope.

‘Whose side are you on?’ is always the unspoken question in politics. Those who want to live in a world that is, for the inheritors, driven by knowledge, asserting the primacy of cooperation, having freedom from as its priority, and motivated by hope will be focused on renewal. Those who want to restore the status quo for the incumbents, basing their political judgements on belief, asserting the dominance of competition, having freedom to as their purpose, and motivated by fear will focus on hanging on.

Answers to all of the practical questions on how to construct a climate-constrained future will be determined by which of the coalitions promoting these alternative world-views wins political power by whatever means.

Whoever does so, will inherit the Earth.