In the run-up to COP30, all eyes are on the world’s most heavily emitting countries to see whether updated commitments to climate ambition in the form of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) will enable the world to preserve fading hope of limiting temperature rises to within 1.5 degrees of warming. But another set of pledges has received relatively little attention: commitments to provide support to developing countries through climate finance pledges.

Previous key moments to increase global climate ambition have been fuelled by renewed pledges from providers of international support, vital for building confidence in developing countries. These have set out how countries intend to contribute to global climate finance goals under the UNFCCC, such as the $100 billion climate finance goal.

Despite a new global goal agreed at COP29 to reach a collective $300 billion by 2035, almost all current pledges expire in 2025 or 2026, and no countries have set out what comes next. This leaves only the joint multilateral development bank (MDB) projection – to provide $120 billion by 2030 and mobilise a further $65 billion from the private sector – as a predictable indicator of the trajectory of future climate finance.

To meet the needs of developing countries, there is a clear need for the private sector to play a role, to increase domestic resource mobilisation, and to broaden the range of countries contributing support. But the immense need for international financial support is inarguable and failure for developed economies to show leadership in providing it risks undermining faith in the global transition. Combined with the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, aid cuts by several other large donors have undermined developing countries’ confidence that the necessary support will materialise.

Of the estimated $1.3 trillion needed in external investment in developing countries (excluding China) by 2035, approximately half is projected to come from public sources. These flows are particularly crucial for the most vulnerable countries, and as catalysts for private finance.

Several countries – including the UK, Canada, Switzerland, and Australia – are actively considering how to increase their climate finance in this shifting context, using the full range of resources available to them. Failure by these countries and others (such as France and Germany, which have played major roles historically but have thus far been silent on their future commitments) to come forward soon will slow implementation and cause further rancour in the COP30 negotiating rooms – an outcome the world cannot afford at a strained time for multilateralism and a pivotal moment for climate action.

The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) agreed at COP29 in Baku represents a vital evolution in climate finance under the Paris Agreement by setting two goals for 2035: developed countries take the lead in mobilising $300 billion for developing countries, and all actors work together to channel $1.3 trillion to developing countries. Nevertheless, climate finance provision – particularly in the form of grants and concessional loans – remains vital for meeting needs and providing political reassurance to developing countries.

New commitments needed

Even in challenging political times, an increase in public finance is a small price to pay to avoid the risks of greater financial, security and humanitarian stressors posed by climate impacts. This is before accounting for the major opportunities for international collaboration to enhance energy security and build shared prosperity in the clean economy of the future. But these pledges must respond to the trends facing global economic development and international partnerships, marking a step change in the evolution of climate finance.

To meet this moment, and in response to the NCQG, governments in wealthy countries must announce new climate finance commitments at (or before) COP30. In the case of developed countries, providing climate finance also represents an obligation (reaffirmed by the International Court of Justice advisory ruling) that underpins the delivery of the Paris Agreement. As COP30 president, Brazil must ensure there is sufficient airtime for such announcements at the Leaders’ Summit and work with contributors ahead of time to encourage ambitious, high-quality pledges.

At their core, climate finance commitments should be designed to accomplish three goals:

- Support effective delivery by channelling the right type of finance to where it is needed.

- Galvanise maximum ambition within all parts of the contributor government.

- Create predictability of delivery for recipient countries and enable comparability of donor efforts.

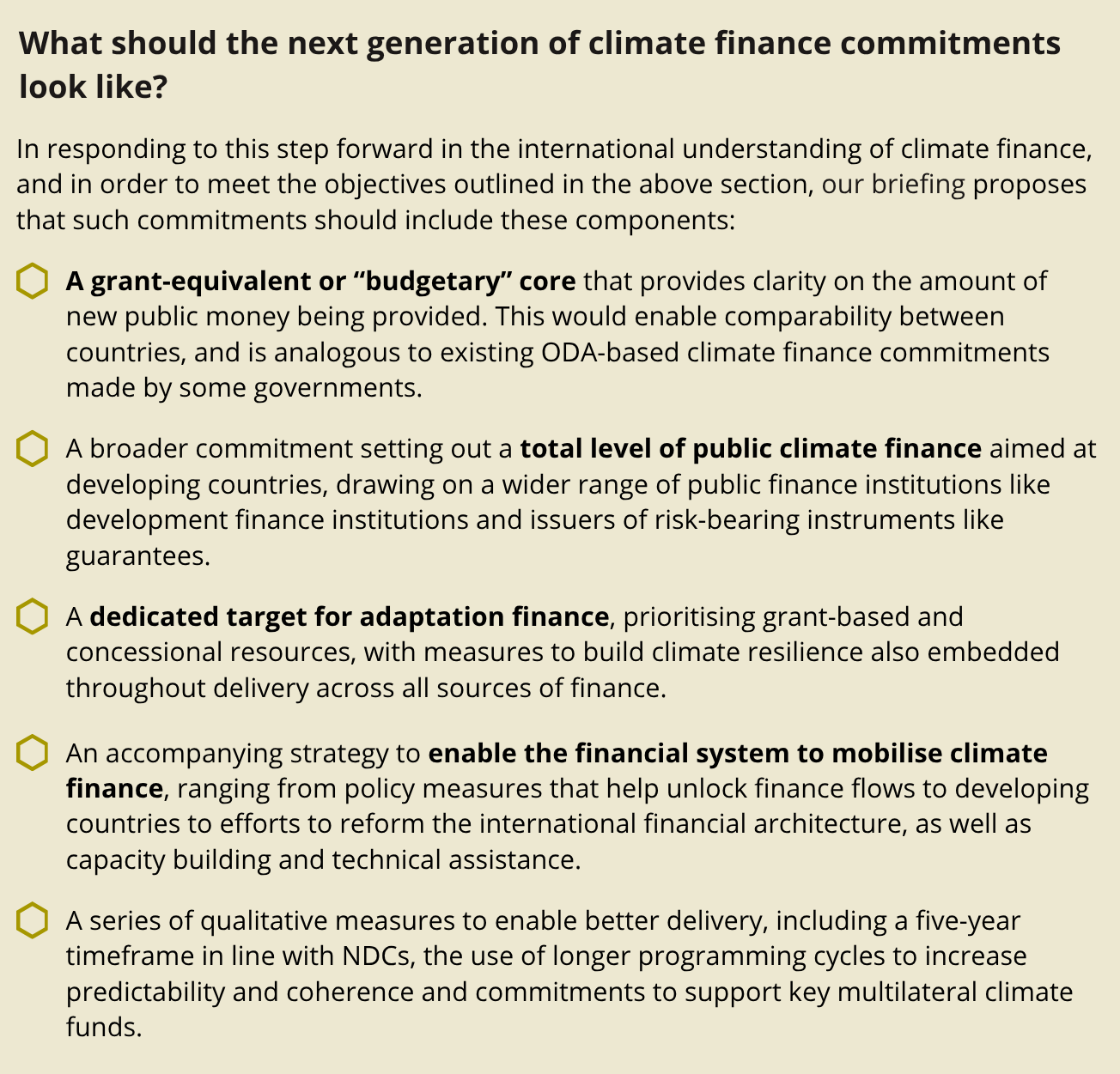

In our accompanying briefing, we provide a checklist for what robust and effective pledges should include. We intend for this to support policymakers and politicians in delivering credible new commitments which maintain international ambition, lay the groundwork for better international collaboration and respond to challenging political and economic times.