On the streets of Maputo, Mozambique, the majority of vehicles have one thing in common: they are at least a decade old. Brand new cars are a rare sight. Electric vehicles are nearly unheard of. Instead, most vehicles have been imported to Mozambique after years of use in Japan.

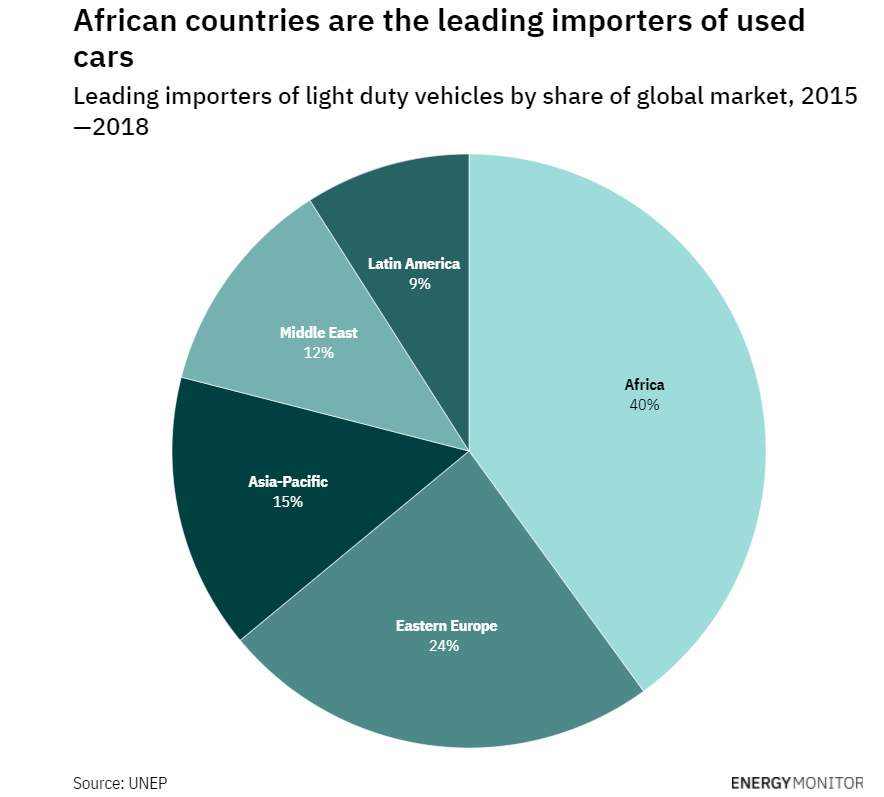

The same is true in many other African countries: 40% of the global exports of used light duty vehicles (cars, vans, SUVs and pickup trucks) go to Africa, compared to only 2% of new vehicles. An estimated 80-90% of vehicles imported to Kenya, Ethiopia and Nigeria are used – and this proportion may be even higher in lower income African countries. In Kenya, the average age of used car imports is 7 years; imports beyond 8 years old are banned. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, most imported vehicles are more than 11 years old; a quarter of vehicles imported to Nigeria are more than 19 years old. Only South Africa, Egypt and Sudan have banned used car imports entirely.

This picture may soon be disrupted: global automotive markets are changing fast. A combination of technology improvements, rapidly falling costs and technology improvements mean that electric mobility is expanding fast in vehicle markets across the world. Major manufacturers are beginning to shift away from internal combustion engine vehicles to producing hybrid or fully electric models. In an “ambitious yet feasible” scenario in line with Paris climate goals, 22% of global vehicle sales could be electric by 2025 and 35% by 2030.

But due to heavy reliance on used car imports and major infrastructure constraints, the pathways for electric vehicles in many African countries is far less clear.

The global shift to electric mobility

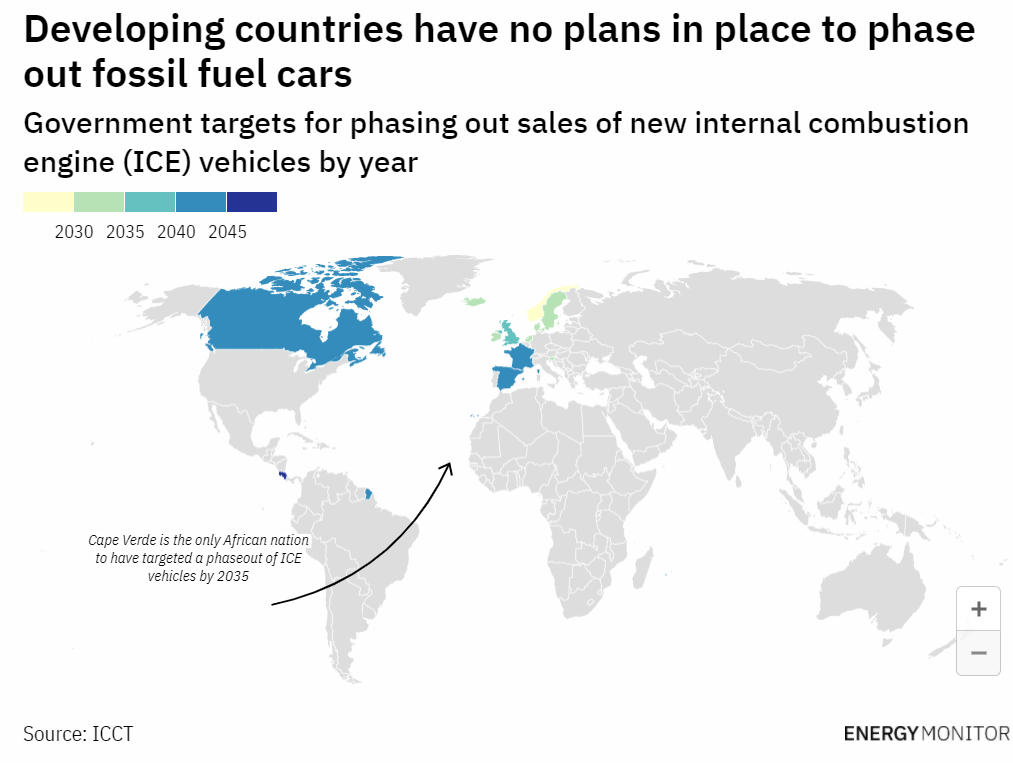

Globally, at least 17 countries have announced phaseout target dates for sales of internal combustion engine vehicles. Only one African country has done so, however: the small island nation of Cape Verde is targeting a phaseout of ICE vehicles by 2040.

Electric cars are still very rare in most of Africa. In South Africa, thought to be the largest EV market on the continent, only 1000 EVs had been purchased by 2019 – out of more than 12 million vehicles on South Africa’s roads. Even fewer electric cars are in operation in most other African countries.

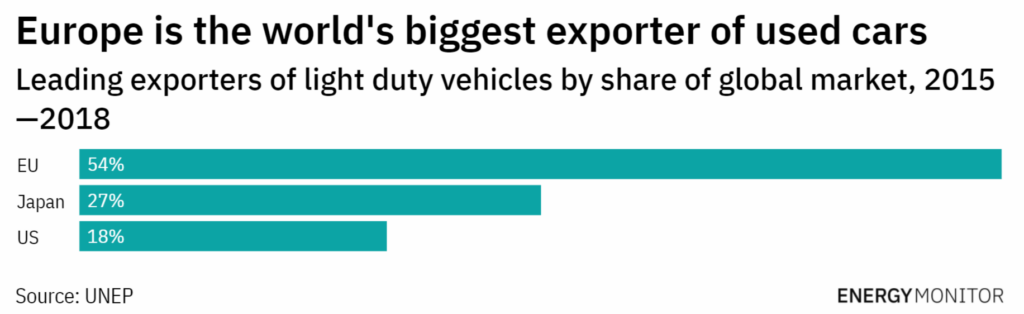

By contrast, electric vehicles are expanding rapidly in the countries responsible for most used vehicle exports. Three regions account for the majority of used vehicle exports globally: Europe (55%), Japan (27%) and the USA (18%).

Europe primarily exports its cars to West and North Africa. Nine European countries have already announced internal combustion engine phaseout targets, and a stronger electrification push is expected across Europe to meet its net zero 2050 goal and stronger new 2030 carbon target.

In Japan, the biggest exporter of used cars to Mozambique and other right-hand-drive countries in Eastern and Southern Africa, a phase-out date of 2035 for internal combustion engine cars has recently been floated, to meet Japan’s new climate targets.

The largest vehicle market in the US, California, has also announced a phase-out of internal combustion engine cars by 2035. Vehicle electrification efforts across the rest of the US are expected to accelerate further under the new Biden administration.

Petrol and diesel dumping

There are different scenarios for how this rapid change in automotive markets in exporting countries will impact importers in Africa.

The first is a “dumping” scenario. A fast exit from internal combustion engine vehicles in rich countries would mean that a flood of redundant petrol and diesel cars are exported to Africa – while vehicle electrification within Africa itself remains sluggish.

This risks exacerbating global environmental inequalities. Health impacts from air pollution within African cities would continue to worsen, even as phasing out diesel and petrol vehicles improves air quality in the rich world.

Dumping of polluting and unroadworthy vehicles in Africa is already a serious problem. A UNEP report in October 2020 warned that:

Millions of used cars, vans and minibuses exported from Europe, the USA and Japan to low- and middle-income countries are hindering efforts to combat climate change. They are contributing to air pollution and are often involved in road accidents. Many of them are of poor quality and would fail road-worthiness tests in the exporting countries.

Taken to its extreme, this scenario could see a Cuba-style prospect of ageing and increasingly obsolete petrol and diesel cars kept running in African countries for years after they exit general circulation in richer countries.

Trickle-down electrification

A second scenario would see electric vehicles begin to “trickle down” to importing countries in Africa once their original owners in Europe, Japan or North America have moved on to newer models. This would see a small number of used EVs exported to Africa over the next few years, but then a far greater number 5-15 years after the electric vehicle market takes off.

This scenario is also problematic. From a climate perspective, relying on a trickle-down of used vehicles will not decarbonise transport in developing countries quickly enough.

The global fleet of light duty vehicles is expected to double by 2050, with 90% of this growth expected in developing and industrialising countries that import used vehicles. However in Paris-compliant decarbonisation scenarios, around 40% of light vehicles in Africa are electric by 2050 – which implies much faster take-up than could be achieved by importing used EVs alone.

But even a relatively slow diffusion of EVs may face challenges in African countries with weak electricity grids. While electricity grids in Europe have easily been able to cope with EV integration, electricity systems in many African countries are already under strain. Frequent brownouts in some countries could limit consumer demand for EVs – as electricity cuts would also cut off access to transport.

Outside of cities, access to electricity to power EVs will also be a challenge. In Mozambique only a third of households have regular electricity access (though the government targets universal energy access by 2030). While most of these households are not car owners, transport services in rural areas such as minibus and motorcycle taxi will struggle to go electric until a more extensive electricity grid is in place.

A further uncertainty relates to the longevity of electric vehicles and how long used EVs will continue to operate. Electric drivetrains have fewer moving parts and therefore less to go wrong. However EV batteries degrade with use and gradually lose range and performance.

A final complication is that the economics of exporting used EVs may turn out to be rather different than exporting used petrol and diesel vehicles. Internal combustion engine vehicles earn relatively little when sold for scrap – and in some cases owners must pay to dispose of them – which provides an incentive to sell used vehicles abroad. For electric vehicles, however, importers face competition: ‘second-life’ EV batteries will be valuable as a source of stationary energy storage, according to McKinsey.

African-led electrification

The third more positive scenario is a more home-grown approach to transport electrification, where the EV market adapts to local needs.

With smart technologies and appropriate regulation, electric vehicles could become an asset rather than a threat to grid stability, through dynamic charging and vehicle-to-grid applications. For consumers affected by regular power cuts, it may be possible to use electric car batteries to power domestic appliances until grid electricity is restored.

And while electricity systems in many African countries are currently limited, they are expanding fast: power generation capacity is expected to more than double by 2040. The shift to transport electrification will be far easier to manage if it is factored in to grid upgrades at an early stage, instead of taking grid operators by surprise further down the line.

In this scenario, it is also likely that electric cars will only be a minority part of Africa’s electric mobility journey. Africa has the smallest per capita car ownership level of any region in the world. Private cars represent a minority of journeys in sub-Saharan Africa. Other segments – buses, shared minibuses, taxis and moto-taxis, motorcycles and even bicycles – may be better suited to electrify first.

A few countries are already tapping in to this potential. In Kigali, Rwandan start-up company Ampersand is introducing a fleet of electric motorcycle taxis and plans to expand to other east African countries. In Uganda, locally-manufactured electric buses from Kiira Motors have started transporting passengers in Kampala. Namibian start-up ebikes4africa has pivoted from its electric bicycles supplying the tourist market – which vanished due to the Covid-19 pandemic – to their use for deliveries by food vendors and pharmacies.

Rather than being merely a dumping ground for the world’s most polluting vehicles, African countries may become a fast-growing source of demand for electric transport, and a source for innovation for new electric mobility technologies and business models. Governments and investors can support this innovation to scale up, and accelerate planning for Africa’s electric vehicle future.

Jonathan Gaventa is an energy policy consultant and a senior associate at E3G, a climate think tank. He is based in Maputo, Mozambique.