2017 may well mark a turning point in getting international oil companies’ (IOCs) to align their business operations with a 1.5/2°C target. Looking back, it may also be viewed as the year IOCs seriously began to consider their own managed decline.

Earlier this year, over 60% of shareholders in ExxonMobil - the world’s largest privately owned IOC – backed a resolution for the company to publish annual assessments of the impact of climate policies on the business. A similar resolution was also proposed at Chevron.

To help develop annual climate policy assessments, shareholders have asked both companies to appoint expert independent directors to the board. So far, only Exxon has complied.

Like Shell and BP, the companies now need to set out how they can best protect shareholder interests in a world where demand for their products is highly likely to substantively decline.

This briefing note examines what happened when we simulated the IOC 1.5/2°C transition in an on-line war game developed by the Oxford Smith School, E3G, and Chatham House. The brief goes on to give insights into the difficult conversations that lie ahead for the boards of these companies.

Background

In a world committed to global temperature increases of no more than 1.5/2°C, the current business models of IOCs and the largest domestic listed companies face significant profitability challenges. Among other factors, profitability challenges for the IOCs are likely to be intensified by several structural factors relating to national oil company (NOC) competition as well as shifting demands for oil and gas. The exact speed and scale of these changes is uncertain. It will depend on policy and regulation to promote clean energy and clean transport; advances in technology; and actions to reduce energy demand through increased energy efficiency. These changes create significant potential for stranded asset risk for the IOCs and therefore significant value loss for private investors. This in turn raises public policy concerns about financial instability and a growing pension deficit in the UK. As such, active consideration of how the IOCs could transition to a 1.5/2°C-compatible business model seems advisable.

War Gaming

The Oxford Smith School, E3G, and Chatham House have created a dynamic decision support tool to explore different pathways companies could take and model impacts on shareholder value. The 2 Degree Pathways decision support tool, is an oil majors war game. This decision support tool helps inform company, investor, government and civil society strategies how to deliver and adapt to various energy transition pathways. The tool does not aim to devise a corporate strategy, but instead highlights the risks and opportunities inherent in a managed transition.

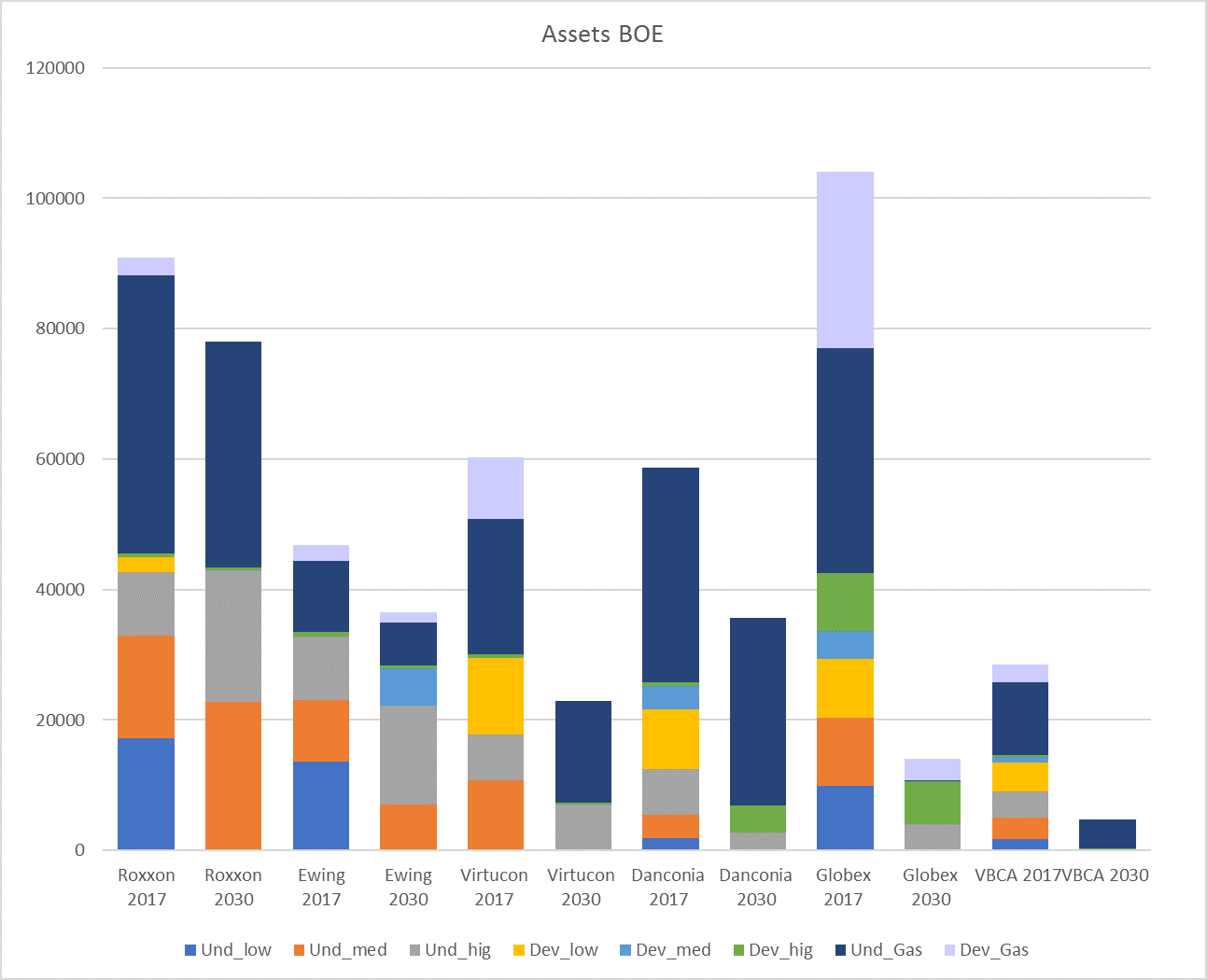

Six fictitious IOCs were created for the game: Roxxon, Ewing, Globex, Virtuocon, Danconcia and VBCA. Each of the IOCs had different portfolios of gas and oil assets at the start of the game that bore resemblance to real IOCs. The player’s task was to role play company board-level decision making. The capital planning time horizon was from 2017 to 2040.

Main Observations

The winning IOC player, Globex, acted differently to most of the other IOCs – responding to policy signals. In the debriefing session, this player acknowledged they had been influenced by their duties under the UK Company Act 2006. Globex achieved success by aggressively divesting its oil assets, before opportunistically buying developed medium cost oil assets when the price crashed.

According to E3G analysis on options open to the IOCs to align with a 1.5/2°C world, this strategy was closest to a ‘Planned transformation strategy’. One tentative conclusion is that a ‘Planned transformation’ strategy such as this will need to be developed early and retained, despite short-term valuation pressures. While Globex’s valuation was initially reduced, in the long run this strategy was vindicated as shareholders received significant dividends and a valuation bounce-back. Despite this however, Globex couldn’t fully wind down all its fossil fuel assets. It was left with approximately 24% of its initial fossil fuel assets, concentrated as undeveloped high cost oil and developed high cost oil and gas (see figure below).

In the real world, this type of strategy would likely need shareholders to explicitly buy-in to a managed decline/divestment strategy run over longer than usual time-periods (up to 15 years). This is more prolonged than the usual market-based ‘long-term’ view of 1-3 years. In this context, to deliver an orderly transition it would be as important to shift investors’ attitudes and expectations on IOC capex and dividend policies, as to shift IOC’s business strategies. Without doing so, a management team trying to execute such a strategy would most likely be ousted before really getting started.

One key observation from the game was that not all assets held by the IOCs could be monetised. Therefore, at some point asset stranding became inevitable as fossil fuel assets became unsellable. Success by players in the game – much as in real life – relied on good timing in terms of developing and/or selling assets. In fact, players could have made good returns up to 2025 by developing their existing reserves base; after 2025 this strategy becomes exhausted.

One final observation is that most players seemed to bet on an increased role for gas as a major climate transition fuel. Based on this they aggressively bought up gas assets, held them and waited for demand to recover. As the years passed the expected gas boom did not come to pass however – and much of the asset stranding observed was unsurprisingly concentrated in gas and high cost oil.

The decline in market valuation that came from the ‘Planned transformation’ strategy deployed by Globex (as well as a ‘First one out’ deployed by VBCA) has some significant implications for a real world IOC ‘First one out’ strategy.

Conclusion

The game indicates that for real IOCs an early and realistic consideration of their options going forward is imperative – including whether a ‘First one out’ or ‘Planned transformation’ strategy is the most appropriate for the Directors to advocate given their obligations under the UK Company Act 2006. Namely, the CEO and management team would need to engage with shareholders at an early stage of strategy development and set out a credible long term plan to align with the reality of a 1.5/2°C world.

In the short-term, a new growth story based on switching capital investment to gas and renewables would seem to be the most credible in keeping shareholders happy. Even that has significant weaknesses however as discussed in separate papers by E3G and Chatham House.

The Directors of the IOCs have their work cut out for them in trying to meet their fiduciary obligations under the UK Companies Act and similar legislation in other jurisdictions.

Market valuation techniques need to evolve to fully reflect the cost of asset stranding. Additionally, better disclosure and communication of a longer-term strategy is important to give IOCs ‘breathing space’ to open meaningful dialogue with investors over how to address disruption to their industry. These actions are also crucial for delivering an orderly transition to 1.5/2°C.