By 2030, the EU must cut its emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels. Agreeing on the target was hard enough. Much harder will be agreeing on the policy design of the rules, regulations and financial support needed to achieve it.

Pieter de Pous at E3G scopes out the major decline already experienced by coal – the worst emitting energy source – before looking at the challenges faced by heavy coal users in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The good news is that wind and solar is still getting cheaper, making the economic case easier every year. But they will depend upon the development of long-term storage solutions and grid modernisation. All this must go hand in hand with the creation of decent careers in clean energy and the re-skilling of coal workers. That mix of technological and social strains means the policies and funding mechanisms matter more than ever. De Pous points to the upcoming revision of the EEAG (Guidelines on State Aid for Environmental Protection and Energy), the EU ETS, and their impact on carbon prices and funding sources. The right policies are needed to make this crucial decade a success for the CEE transition.

The EU’s climate and energy debate has moved from the question of speed to the question of design. By 2030, the EU will have cut its emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels.

Agreeing to this new level of ambition came after long negotiations involving multiple all-nighters among EU heads of government. The economic and social implications of the energy transition were cited as a major concern for Central Eastern European (CEE) countries and were behind the reluctance of some of them to agree to more ambitious climate goals.

Coal is already on its way out

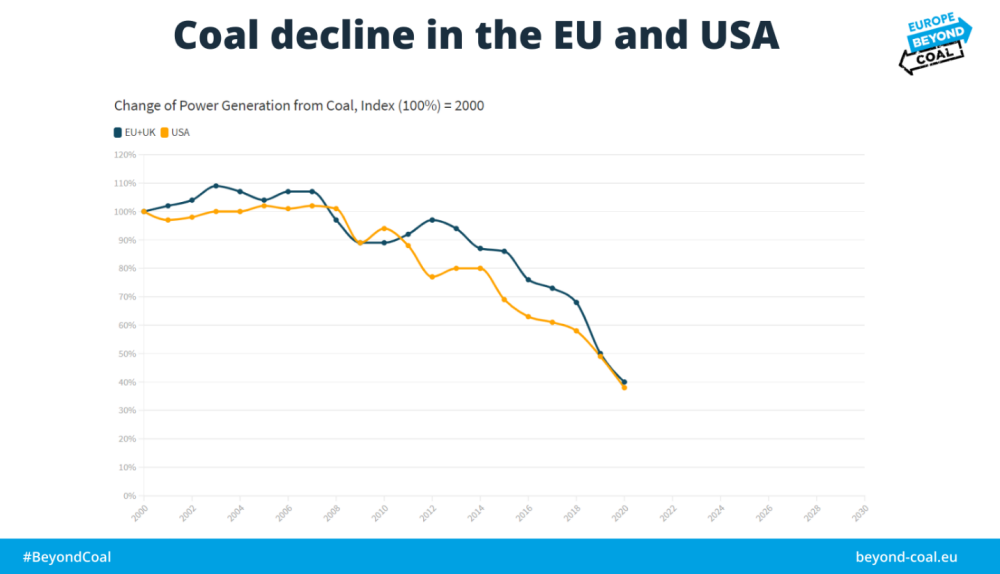

This political debate, however, has sometimes obscured the fact that energy markets have already changed profoundly. The economics of coal-fired electricity generation have already been deteriorating for years, leading to a reduction in coal generation across Europe of over 50% between 2012 and 2020. Just the year 2018-2019, before the COVID pandemic, saw a fall of 24%. And 65% of the remaining European coal power plants’ capacity is already covered by a phase-out commitment.

Declining economics are already impacting European Commission probes into state aid such as German compensation for lignite. And while gas is seen as an alternative to coal, gas power plants are already under pressure from cheaper renewables just as coal is, as Carbon Tracker analysis for Italy recently found.

Across the world the picture is a similar one. The pipeline of new coal plants has been evaporating in countries like Turkey and Egypt. During the time of the Trump administration, the US coal fleet continued to retire at the exact same rate as before, despite every effort made to turn that trend around. In fact, the EU and the US are both on a track to becoming coal free by 2030 if existing trends continue.

A landmark report, “How to retire early”, found that by 2025 all coal plants in Europe, including in CEE, will be uncompetitive when compared with an alternative combination of onshore wind, utility-scale solar PV and four hours of battery storage. Capacity mechanisms may shield coal plants for a few more years, but by 2030 at the latest most of these contracts will have ended.

Coal’s transition in Central & Eastern Europe

The biggest challenge for coal countries now lies in pushing hard on the technical, administrative and institutional boundaries to speed up the rollout of cheaper renewable capacities to allow the retirement of money-burning coal assets. This effort needs to be supported by the development of longer-term storage solutions, modernising the grid to allow for the integration of high shares of renewable energy, ensuring jobs in clean energy benefit from union representation and reskilling of coal plant and mining workers.

To address some of these challenges, CEE countries can draw from the experience of other countries that are more advanced in the coal to clean transition. This includes the UK National Grid, which has already been managing extended periods of a coal-free power mix and is now planning to be operating its first fossil free day in 2025, or Spain, which has agreed a comprehensive Just Transition package with its unions.

Within the CEE region, the green race has started too. Both Slovakia and Hungary have joined the international Powering Past Coal Alliance, the region of Greater Poland (west-central Poland) is planning to terminate its lignite operations by 2030 and Poland is planning for a 23% share of RES in 2030 after seeing its solar PV capacities triple in the last year alone. A new report by Instrat found that if Poland were to align its energy policy with the EU’s new 55% target, it would be a factor 4 cheaper than current plans being considered.

In 2019, Tesla’s decision to build its first European Gigafactory in Germany and near Poland was motivated by Poland’s high coal mix. Now, Polish wind energy manufacturers are partnering with energy-intensive industry to develop renewable power purchase agreements, in response to concerns about the high energy prices associated with coal. Czechia too is considering a coal phase-out date. New nuclear is another option considered, though not relevant to the achievement of climate targets for 2030.

Revision of the EEAG and other EU policies

For CEE countries to overcome these challenges it will need the right EU policy framework and, just as much, the right national government policies to seize the opportunities. The adoption of the EU’s Just Transition Fund, an entirely new financial instrument, already provides an important first step with several more to come.

The revision of the Guidelines on State Aid for Environmental Protection and Energy (EEAG), planned for later this year, will play a particularly important role to ensure a strong alignment between national investments with European Green Deal objectives, as most coal plants in Europe will soon be running at a loss. An overhaul of the Emissions Trading Scheme Directive to align with the new 2030 target is expected to lead to carbon prices between 56-89 EUR per ton in 2030, which will accelerate the coal to clean transition as well as providing revenues for a revised Modernisation Fund.

Globally, a debate about developing dedicated financial instruments for early coal retirements, pioneered in US states and currently considered by the World Bank’s Climate Investment Fund, is gaining traction. These instruments are designed to help coal-heavy utilities gain access to cheaper sources of capital as part of a deal that sees the utilities swap their coal assets for cheaper renewables.

In short, conditions for the CEE region to catch up in the clean energy transition have never been better, provided EU governments now develop policies that take advantage of new economic realities.