Das Ende Der Wende?

After the dizzying speed and scale of the EU response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the familiar anticlimax has set in. Deep-seated national interests are reasserting themselves and longstanding fault lines are reappearing in fiscal policy, energy security and defence. Has Wendepolitik spluttered to a premature halt? Or is this merely a pause for breath?

While the EU has presented plans to reduce demand for Russian gas by two thirds before the end of the year and become fully independent of Russian fossil fuels “well before” 2030, there is no political appetite for an immediate boycott.

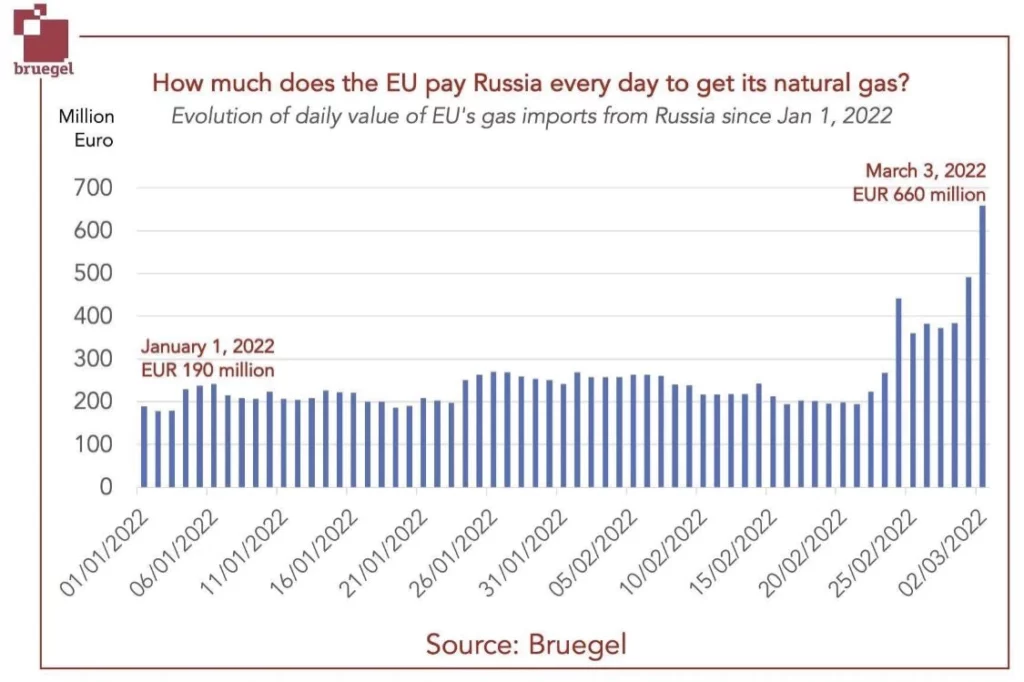

According to Bruegel, the current export value of Russian piped gas to the EU is just short of €700 million dollars a day. Research from the NGO Transport & Environment puts the daily value of Russian oil exports to the union at $285 million.

Given that revenues from oil and gas-related taxes and export tariffs accounted for 45% of Russia’s federal budget in January 2022, the continued flow of energy revenues and the escalating prices for these commodities has significantly cushioned the blow of the wider sanctions regime and enabled Putin to finance his war.

This is most visible in the rebound in the value of the rouble: while Russia’s currency initially lost half its value against the dollar, it has now recovered to a rate about 30 per cent below its prewar level.

As the EU’s biggest importer of Russian fossil fuels, Germany is at the sharp end of these contradictions.

In pushing back against calls from Eastern member states like Poland and Czechia for an immediate ban, the government has argued that this would plunge Germany and all of Europe into a recession, with Chancellor Olaf Scholz warning that “hundreds of thousands of jobs would be at risk, entire industries would be on the brink.” These claims have been presented with little empirical evidence. Indeed, the most sophisticated external analysis suggests that they are overstated:

We combine macro data, household micro data, & state-of-the-art theory to derive at 4 key findings

— Moritz Kuhn (@kuhnmo) March 7, 2022

(1) Stop of Russian energy imports would lead to a GDP decline bw 0.2% and 3%. Range depends on possibilities to adjust gas usage (baseline 0.3%, very conservative estimate 3%) 3/ pic.twitter.com/Qhkaejwc4l

At the weekend, Scholz doubled down on his refusal to contemplate an energy boycott, arguing that Putin could not use the hard currency because of existing sanctions, and excoriating economists who advocate this. Not only are they “wrong,” he told German television, but “honestly irresponsible to calculate around with some mathematical models that don’t really work.”

The Government’s reluctance to cut off this key source of funding for Putin’s war machine is better explained as a response to shifting public opinion. While support for Ukraine remains strong, the willingness to tolerate material sacrifices in pursuit of this is weakening:

SURVEY: Die 🇩🇪 Zeitenwende continues to un-wende:

— Ryan Bridges (@ryanbridgesgpf) March 23, 2022

After previously (8-10 Mar) SUPPORTING a 🇷🇺 oil/gas ban 55-39…

Germans now OPPOSE a gas ban 48-41.

Oil ban support is just 48-42.

Compare to:

4 Mar: 60-28 support gas ban

7-9 Mar: 54-38 support oil ban

Lobbying works. pic.twitter.com/6auvhioBxY

The contradictions of German policy were exploded by President Zelensky’s address to the Bundestag on March 17th, where he excoriated the country’s prioritisation of its own narrow economic interests over its obligation to try to end the war by turning off the energy spigot. The effect was to send Ostpolitik’s tainted successor “change through trade” to the dustbin of history:

I am grateful to the German businessmen who put morality and humanity above accounting. Above the economy. Economy. Economy. And I am grateful to the politicians who are still trying… Trying to break this Wall. Who choose life between Russian money and the deaths of Ukrainian children. Who support the strengthening of sanctions against Russia that can guarantee peace. Peace to Ukraine. Peace to Europe. Who do not hesitate to disconnect Russia from SWIFT. Who know that an embargo on trade with Russia is needed. On imports of everything that sponsors this war.

Wendepolitik has unfolded at bewildering speed. For now, as it relates to the choices on energy, defence or fiscal policy that this historical turning point demands, it is merely an aspiration for which there is no clear public or political consensus within Germany.

But Germany alone will not decide the course of European politics and statecraft: from the ashes of the old, discredited Ostpolitik, and with Zelensky leading the charge, a new Ostpolitik is coming into view.

This article was originally published by Ed Brophy on the Fault Lines. Read the original here.