The renewable energy sector has had a remarkable decade. The biggest renewable energy success story in the last 10 years is not measured in gigawatts, but in lives transformed. Off-grid solar represents a tiny proportion of global electricity output, but has brought access to lighting and other energy services to hundreds of millions worldwide.

The growth of the off-grid solar market is based on catering directly to a large but much-neglected consumer segment: poor rural households without access to grid electricity. These consumers have limited spending power but strong unmet demand for energy services, and the potential size of the market stretches to hundreds of millions of customers. While many of these households will eventually connect to centralised electricity grids in the long run, the glacial pace of grid expansion in many countries means that off-grid solar offers the best opportunity of expanding energy access quickly.

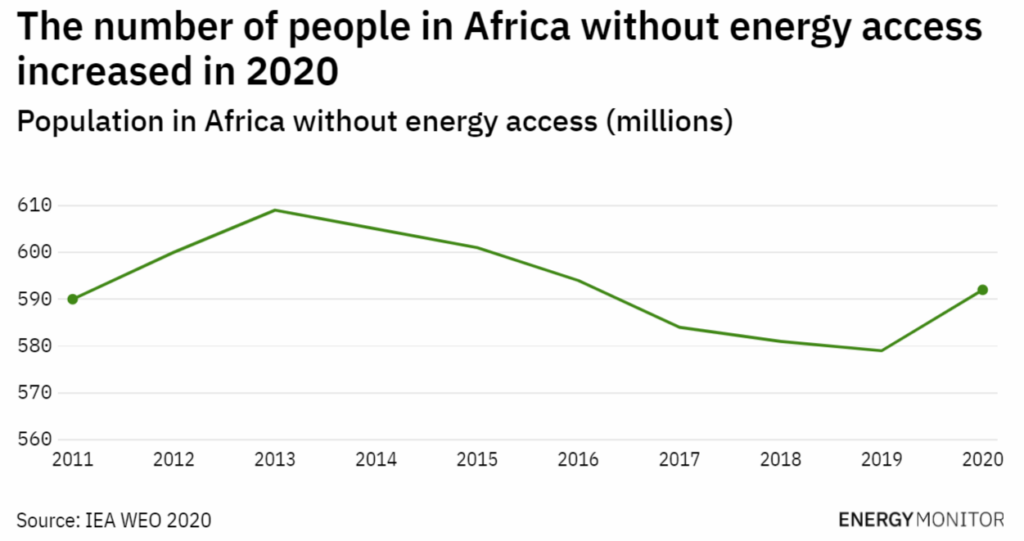

This story of success, however, is on the edge of becoming a story of crisis. The economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly hard on low-income consumers in developing countries – the very same customers that underpin the off-grid solar market. As a result of this economic shock, sales and repayments have shrunk and dozens of off-grid solar companies are now on the brink of collapse.

If the sector can survive the immediate crisis, off-grid solar will play a key role in post-COVID recovery for least developed countries, by creating jobs and underpinning economic opportunities. As governments and international institutions begin to develop economic recovery strategies, a financial rescue mission for off-grid solar is needed to put the sector back on a solid footing.

The rise of off-grid solar

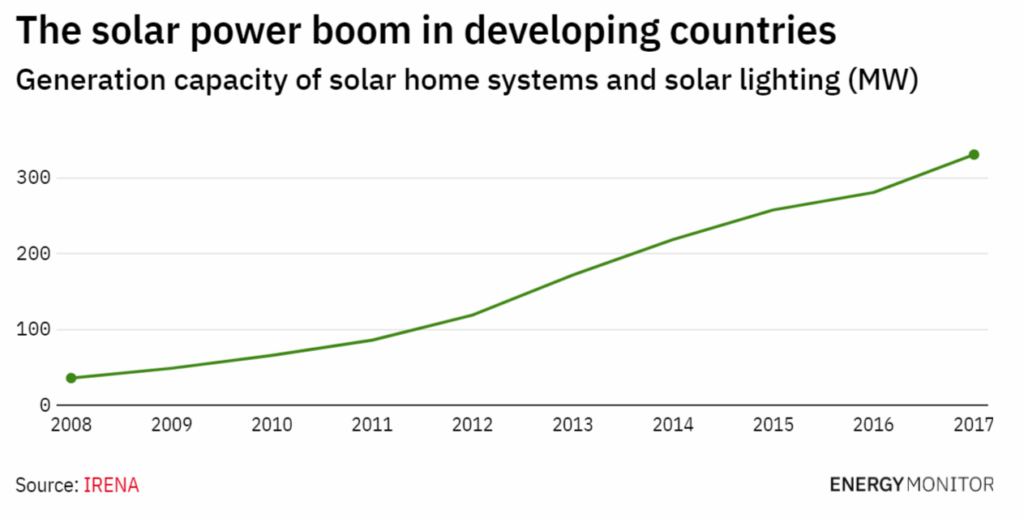

A decade ago, off-grid solar was a niche, barely-existing industry. Since then, the sector has seen €1.5bn of investment. More than 180 million solar units have been sold, providing energy services to over 420 million people.

The off-grid solar market comes in different forms, ranging from ‘pico-solar’ products such as solar lanterns, to solar home systems, agricultural and commercial applications and solar-powered mini-grids.

These products are on a completely different scale to other parts of the solar PV market. A solar home system may have a capacity of 10-100 watts. A domestic rooftop solar system in the US or Europe is 100 times larger (1-10 kW). The world’s largest grid-scale solar arrays are now over 2 GW – or 20-200 million times the capacity of a typical off-grid solar home system.

The small scale of the product means that despite reaching hundreds of millions of customers, the total installed capacity of off-grid solar homes systems globally was only 331 MW in 2017 (slightly less than the total grid-connected solar capacity in Scotland alone, for example).

The fall in income for poor energy consumers cascades into vanishing revenues for off-grid solar companies, as their customers struggle to make repayments.

The rise in poverty – combined with COVID-related restrictions on business activities – is also reducing sales of off-grid solar. After seeing annual growth rates of over 30% a year, sales of solar homes systems fell by 26% in the first half of 2020. Two-thirds of companies report that sales of energy access products have fallen by more than 25% compared to last year, and nearly a fifth experienced a drop of over 75%.

Meanwhile, capital flight from least developed countries means that companies operating in these regions face considerably higher financing costs, while currency devaluation makes imports of solar equipment more expensive.

To make matters worse, some international donors who have supported energy access are either reducing development spending or refocusing on the immediate COVID response instead of energy.

This confluence of impacts means that many off-grid solar companies are at risk of going out of business entirely. A survey in July of 600 energy access companies found that 85% were concerned about their ability to last until the end of the year. While larger international companies with strong financial backing will be able to weather the storm, local companies will be particularly badly affected.

Can off-grid solar rise again?

The future of the off-grid solar sector has become unclear in the wake of COVID-19. Small-scale off-grid solar was in some respects always going to be a temporary market – filling in the gaps left by the slow growth in grid connections. As incomes rise, centralised grids, mini-grids and larger solar installations will be needed to meet more complex energy needs than can be provided through simple solar home systems.

But grid expansion can take decades, and energy needs are immediate. With energy access shrinking in the wake of the pandemic, the damage to the sector is a real cause for concern.

If the sector can get past the immediate impacts of the pandemic, however, it will play an important role in the post-COVID recovery, through supporting health outcomes, creating jobs and serving as an enabler for wider economic activity.

In the near term, there is an urgent need for a programme to provide off-grid solar and refrigeration to rural health clinics, which often lack reliable electricity. The efforts to secure access to vaccines for the world’s poorest countries will be wasted if they cannot be stored properly.

As developing countries rebuild from the economic shock, the off-grid solar sector can be an important source of employment, As of 2019, the off-grid solar sector supported 370,000 jobs, and – before COVID hit – this was expected to grow to 1.3 million jobs by 2022. The majority of these jobs are in rural areas, supporting employment in disadvantaged communities.

Off-grid solar also plays an important role in enabling wider economic activity. A fifth of users report using lighting and other energy services to support income generation activities, from charging phones to running small shops to home-based crafts. In East Africa, this additional economic activity is equivalent to 21 full time jobs for every 100 solar homes systems sold.

Saving the sector

For the off-grid solar sector to contribute to the post-COVID recovery, first it has to survive. To avert the immediate crisis, international institutions and donors should repurpose existing energy programmes to focus on the simple aim of keeping the off-grid sector going – and inject more capital if existing programmes are not enough.

Developing country governments have a critical role in supporting the survival of the off-grid solar sector. Off-grid often gets less attention than grid-connected generation in national energy strategies, even where it reaches large numbers of consumers. Unnecessary hurdles limit the growth of the sector. In Mozambique for example, customs and duties can add 40% to the cost of imported equipment, meaning fewer households can afford even the most basic solar home systems. Meanwhile in Kenya, VAT was re-imposed on off-grid solar products earlier this year as the government sought to make up from a shortfall in revenues triggered by the pandemic.

Governments, international institutions and development organisations are now beginning to design post-COVID economic recovery programmes, often with commitments to build back better and build back greener. Off-grid solar should be a core part of these plans. A combination of targeted financial and policy support for off-grid solar in recovery programmes can help to make sure the off-grid solar sector not only survives but thrives – and delivers improved energy access, more economic opportunities and better health outcomes for millions more people.