The Climate Ambition Summit was a 6-hour marathon of speeches, platitudes and some world leaders pledging greater climate action. But what does it all really mean, and where does it leave us going into 2021?

Last Saturday the UK, UN and France convened 75 world leaders with representatives of business, economic sectors, and cities in a celebration of the 5th anniversary of the signing of the Paris Agreement. The bar to entry was set relatively high: countries would only be allowed the stage if they committed a new increase in ambition for their 2030 nationally determined contribution (NDC), announced a net zero target, significantly increased their climate finance, and/or shared new adaptation plans and initiatives. This bar kept the worst greenwashing – from the likes of Brazil and Australia – off the stage, but for several countries, it’s still questionable what truly new ambition was announced.

E3G tracked the new announcements on the day and you can re-live all the highlight and lowlight moments in our Twitter threads here, here, and here. The headline assessment was best summarised by the COP26 President-designate Alok Sharma himself: had the Climate Ambition Summit made progress? “Yes”. (The UK published their take on the new commitments collected here). But was the progress made at the summit enough? “No”.

What progress did the Climate Ambition Summit demonstrate?

- Firstly, the Climate Ambition Summit has reinforced the decisive shift in the future of our global economy. With Argentina confirming it would adopt a 2050 net zero target, in effect, it now means that a majority of the world’s 20 largest economies are committed to net zero. The direction of travel is unmistakeable – if other G20 countries fail to adopt net zero as their goal, they risk being left behind in the future of global markets.

- A few exciting clean energy transition announcements reinforced this direction of travel: a ‘no new coal’ announcement by Pakistan and the phase-out of public overseas fossil fuel financing from the UK added to Denmark’s pre-summit announcement of an end to oil and gas exploration. While China’s overall set of announcements was underwhelming, the new commitment to increasing installed wind and solar capacity to 1200GW by 2030 is a big leap.

- The economic shift also reflects a political shift. While the summit seems to have largely played into the “climate bubble” – after all, how many people spend their Saturdays watching a climate summit? – it demonstrates nonetheless the power of climate change as a top-priority issue to convene world leaders, despite high geopolitical tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic. The UN Secretary-General used the political platform to set newly bold calls on countries to do more; to declare a state of climate emergency until carbon neutrality is reached, and to take bold action now to align with that objective. Responses to this ‘state of emergency’ framing will be one to watch in 2021.

Where did the Summit fall short?

- Countries are still slow to turn their net zero goals into aligned short-term targets and deliver credible immediate action to back it up. The Summit showed the Paris Agreement’s ‘ratcheting mechanism’ – whereby countries progressively raise their climate ambition every 5 years – is starting to work in some parts of the world, but there’s a way to go yet. Climate vulnerable countries continue to show leadership – with 19 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) on course to submit 2030 NDCs before end of the year, but 2021 needs to see major economies set near term ambition and policies that match this leadership. The UK’s and EU’s new 2030 NDC targets announced in time for the Summit are heading in the right direction. The USA, Japan and South Korea will be priority countries to set higher 2030 ambition in 2021 in line with their net zero goals. China is of immediate concern, as there is a risk of them cementing the incremental updates announced at the summit as the official update of their NDC by the end of the year. The emerging view amongst experts is that while China’s updates are a first step, they do not in and of themselves lend credibility to China’s 2060 carbon-neutrality pathway.

- Leaders were surprisingly quiet on the topic of green recovery. Meanwhile the numbers are loud and clear: the majority of G20 recovery finance to date has backed fossil fuels. As the recent UNEP Emissions Gap report showed, a low-carbon pandemic recovery could cut 25 per cent off the greenhouse emissions expected in 2030, based on policies in place before COVID-19. Far greater attention to this will be needed in 2021, starting with G7-level agreements around benchmarks for green recovery, to avoid undermining the commitments made at the Summit.

- The Summit again exposed the major gaps in availability and accessibility of climate finance, with only miniscule new amounts pledged at the Summit. On a positive note, strong messages from the UNSG, Alok Sharma, and climate vulnerable countries have started to make the clear link between climate action, climate finance, and broader finance for development and economic recovery. The UK’s announcement of plans to hold a climate and development Summit in early 2021 could help address these gaps, particularly if solutions are co-designed with climate vulnerable developing countries.

Where does this leave us going into 2021?

During his closing speech, Alok Sharma set out a solid framework for the year ahead – with four priorities:

- Urgent action on near-term mitigation ambition, ahead of COP26 including on economic sector campaigns to make the decisive shift to delivery

- A step change on adaptation action, building on the new Race to Resilience, and committing to convene countries, donors, investors and civil society

- Getting finance flowing, meeting the promise of providing $100bn a year in climate finance to developing countries, not ignoring the challenge of loss and damage, and addressing the wider debt and fiscal crises that low- and middle-income countries are facing in light of the COVID pandemic

- Driving international cooperation, weaving climate as a golden thread through next year

It’s evident from this speech that the COP26 Presidency has the beginning of a clearer roadmap to COP26 – setting out priority issues and opportunities where these will be addressed throughout 2021. Encouragingly, Alok Sharma pointed to the G7 and G20 as key venues for linked action.

What we hope the COP26 President Designate reflects on over the holiday break

- Climate finance The COP26 President’s strong call for donors to step up action is warmly welcome, but it’s still unclear how the UK intends to get donor countries to match its commitment to doubling international climate finance when it’s recently slashed its own aid budget under the same fiscal pressure caused by COVID-19 that all donors face.

- Adaptation Intimately connected to the issue of finance is that of adaptation, which was rightly highlighted as a priority area for next year. But it’s still not clear how the Presidency believes it can use its convening power to drive a real step-change. To do so will certainly require the UK to build up buy-in and trust with climate-vulnerable developing countries.

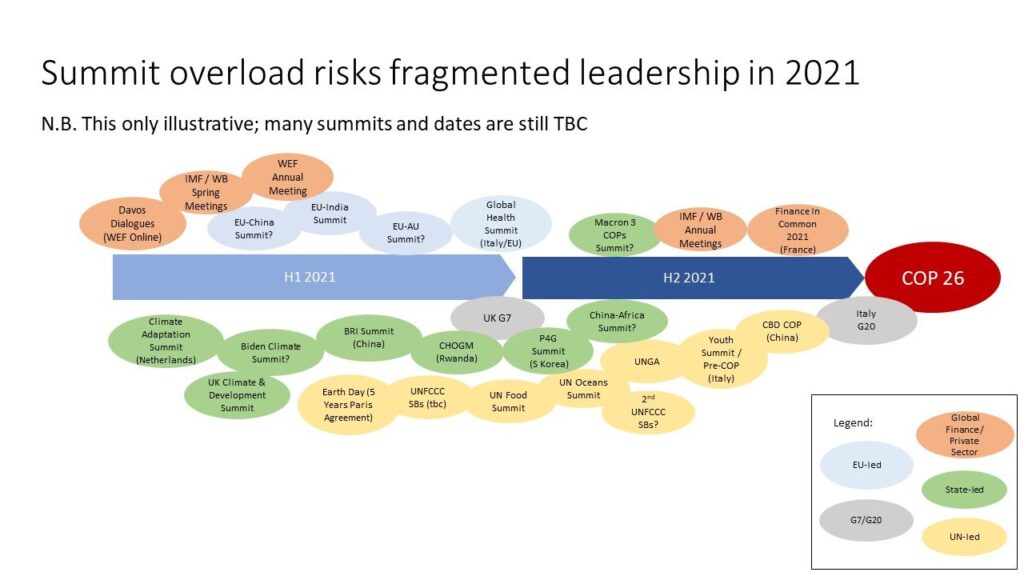

- Summit overload & distributed leadership In a landscape so dense with leaders level moments (just look at our indicative summit calendar for 2021 above), summits risk being largely empty without significant coalition building well in advance that gets countries in the position to announce something strong at these landing grounds. To make this happen the UK needs to join forces with other major summit hosts (Italy’s G20, the EU’s global health summit, and Biden’s planned major economies climate summit) while also bridging global south voices and summits. Building this distributed leadership will be key to managing the busy 2021 diplomatic calendar and handling how the US reintegrates with global climate diplomacy.