In Visegrad countries, decision makers give preference to their historical favourites – coal and nuclear – over renewable energy and energy efficiency. At the occasion of the Global Climate Action Summit, which celebrates the achievement of non-state actors, it’s important to realise that corporate leadership can also shape the outlook for clean energy in Eastern Europe.

The EU’s vision for a modern, clean and competitive economy has difficulties sifting through the thick air of V4 capitals. Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia seem burdened by old traditions of state-controlled and centralised decisions when it comes to defining a future for their electricity sector. Attachment to coal and nuclear prevails on top of the political agenda, whilst renewable energy and energy efficiency rarely get mentioned. Decision makers remain fervent believers of centralised and large infrastructure projects, and sceptical of distributed energy.

While studying the political economy of climate and energy in these countries, E3G assessed the extent of the high carbon industry’s influence in the V4. The leading companies have good and historic connection to the state, as most of them are still state owned. As such, they still manage to lay the institutional, economic as well as legislative framework, sometimes contrary to EU values, rules and long-term targets. In comparison, the low carbon economy is weak and often very much divided, and therefore much less influent.

An extremely unstable, and often genuinely hostile legislative framework towards renewable energy gives little hope of promptly moving beyond this status quo. V4 governments and parliaments have been known to revamp legislation from one week to the next, blocking renewable energy expansion. This has deterred the appetite of many an investor and have made these countries less attractive in comparison to Western Europe. Due to these circumstances – low capacity, low profitability, unstable regulation, etc. – the ability for the renewables industry to invest in advocacy has declined significantly. By now there is only a dozen paid professionals working in the Visegrad Group on improving renewable energy policy.

Despite significant potential, wind seemingly stops at the Austrian border. Austria has over 3GW of wind power already, although its geography doesn’t really favour this technology. On the other side of the border, Hungary has only installed around 300MW, with licences distributed back in 2006. Not a single permit has been issued since then and a recent change in regulation prohibits any new development. In Czech Republic, the installed wind capacity also barely exceeds 300MW; in Slovakia, wind is not even mentioned in official policy documents, and there are only two little wind farms in the country. With its 5.8GW of installed capacity and its rank as 7th in the EU in terms of largest wind capacity, Poland stands out. Nevertheless, wind power development was halted in 2016 when the government introduced a spatial planning regulation similar to the one Hungary had put in place, which suggests that Poland’s vast potential onshore and offshore will remain untapped for the foreseeable future.

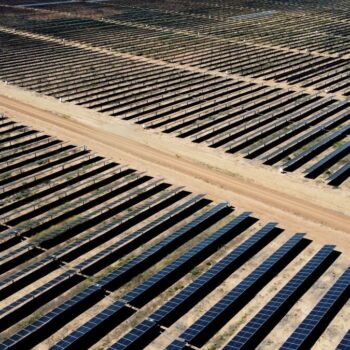

The solar story is similar. The Czechs were the pioneers in the region, generating a solar boom with a generous feed-in tariff in 2005, resulting in 2GW installed capacity up until now. But following a political scandal suggesting state capture, renewables were blamed for the increased electricity price. This was reason enough for the other countries in the region to point fingers and refrain from supporting this technology. In the three other V4 countries, practically no electricity is generated from solar installations, although Hungary has distributed around 1GW worth of new licences which are expected to be built in the coming months. Both Poland and Slovakia claim problems with the grid to accommodate this distributed energy and the Slovak regulator oblige any new producers to consume at least 90% of the generated electricity on site – a truly constraining requirement.

Energy efficiency is not progressing well in the region either, despite a significant increase of EU funds channelled into this sector. BPIE finds that “only 3% of the public funds that could be used to support energy-efficiency investments in the Central, Eastern and South-East Europe region are dedicated to upgrading buildings“. They add that despite severe energy poverty and energy security concerns, politicians fail to consider buildings as critical energy infrastructure, despite the potential of deep renovation to reduce energy dependency, increase savings on energy bills and improve health and air quality.

This gloomy outlook cries for outside help, that corporate leadership can provide. Significant foreign investment is going to the region, which repeatedly shows promising outlook for car manufacturing, IT, software development, etc. By creating corporate demand for clean energy, companies operating in the region can significantly contribute to changing the outlook for the low carbon economy in the region. By showing how moving renewable energy can also reduce business risk, they can also contribute to demonstrating the benefits of clean energy.